Everyone knows about the Kremlin's trolls, but what about its ogres? In a time when much of politics is about signal and drama, it needs figures to represent the worst, the most dangerous, the most unpredictable side of the system. Yevgeny Prigozhin appears to be the latest figure to assume this role.

Rather than a Power Vertical, with all its implications of rigid discipline and a clear, universal hierarchy of command, today's Russia has a Power Theatrical. Beyond the overt expressions of Kremlin will, the presidential decrees and ministerial resolutions, there are many more expressions of governance by hint and whisper, shadowplay and pantomime.

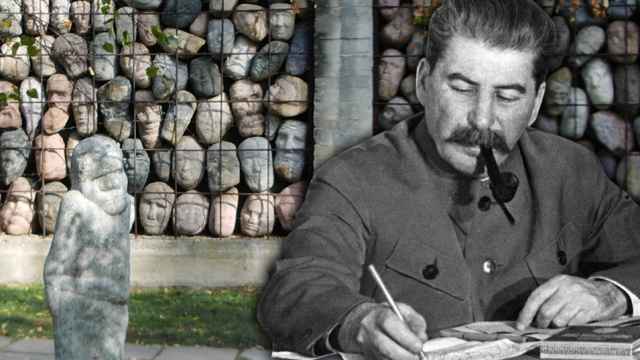

A particular role in these dramas is that of the ogre-oprichnik, the fearsome agent of the Kremlin who is only partly bound by his chains. His role is at once to be a cautionary tale — do what you’re told or the ogre will get you — and also a legitimate role, as the sacral king is known in part by his ability to keep the ogre in check. Without the king, the implication is, the ogre would be unbound.

The leader of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov is the longest-running ogre, a man who can bring together the traditional Russian image of the wild man of the south, the traditional Chechen image of the abreg, or bandit avenger, and a very modern image of the gangster.

The very fact that even today there are those who believe — implausibly — that he could be a king or kingmaker himself outside Chechnya speaks to the power of his performance.

How long before the villain demands a starring role, though, and the right to edit the script? Kadyrov is an increasingly uncomfortable ogre for the Kremlin itself, as he plays violent border games with Ingushetia and demands absolute guarantees for the generous federal subsidies that bankroll his regime.

Perhaps the crucial turning point was the murder of Boris Nemtsov by members of his security forces. Whether Kadyrov had instigated the killing or not, he certainly stood by his men. This was not a deniable act of Kremlin violence but an embarrassment and a shock to the Moscow elites who had believed Kadyrov was their tame monster.

Then there was Alexander Bastrykin, witchfinder-general of the newly-independent Investigative Committee. An enthusiastic prosecutor of the outspoken and the out-of-favour, his zeal was guaranteed by the fact that he was himself something of an outsider, without a cadre of allies, friends, patrons and clients, and so needed to demonstrate his loyalty daily.

Over time, though, he may have got tired, but certainly the dramatic value of his role as ogre declined. No matter, though, a keen understudy was ready to step into his shoes, Viktor Zolotov, once Vladimir Putin's chief of security and now head of the National Guard.

With his thuggish demeanour, his reputation for unpredictable violence, and the National Guard at his disposal, Zolotov represented a useful ogre who, better yet, lacked the independent power base that allows Kadyrov such latitude.

For a while, Zolotovshchina replace Bastrykinshchina as liberal nightmare de jour. The Rosgvardiya were being presented as the faceless stormtroopers of potential repression.

However, cops and conscripts lack quite the same mythic aura as Chechen gunmen, especially as Telegram channels and online fora began to feature grumbles and heart-searches from the ranks, as they made it clear that they were unhappy with the thought of being the extras in Zolotov's intimidating drama.

Zolotov remains one of the most loyal and potentially dangerous of Putin's cronies. But his value as the designated ogre in drama if not in reality may be in question. Alexei Navalny's carefully-judged claims that he was embezzling at the expense of his own men did him no favours.

His clownish responses were even more problematic, one thing no ogre can afford to be is a laughing stock.

And so it is time for a new player to join the ensemble, or rather a jobbing supporting actor to step forward to the front of the stage. Prigozhin's career has been that of the quintessential adhocrat, doing whatever the Kremlin wanted done. He was 'Putin's chef' organising dinners and feeding the troops.

Then he was the master of the trolls. Next, it was the role of Kremlin condottiere, managing the Wagner private military company was it battled its way across Syria and then spread into Africa.

Now, he may be the latest to audition for the role of ogre. The continued rumours of the murders of investigative journalists in the Central African Republic and dirty trucks carried out at home on his orders. His vitriolic manner. His look. All make him a perfectly viable candidate.

The first real sign that he is combining theatrical with practical roles is arguably the attempt to suggest Navalny met with him in St. Petersburg last weekend.

The urgency with which Navalny's team debunked the idea demonstrates how toxic Prigozhin's own reputation has become, and the risks in any presumed association. This is a new way of adding to the ogre's roles, as befits the arrival of a new actor.

Either way, though, it once again demonstrates the way that this is not dictatorship but dramaturgiya.

Prof. Mark Galeotti is a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute and Jean Monnet Fellow at the European University Institute and the author of “We Need To Talk About Putin.” The views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.