Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin may have been reticent to celebrate the centenary of the Bolshevik Revolution, but it had no qualms about celebrating a hundred years since the founding of the Cheka, Lenin’s political police, on Dec. 20.

Alexander Bortnikov, head of the Federal Security Service (FSB) and a veteran of the old Soviet KGB, was predictable in his message. His agency was, he claimed, “free from political influence.” It “does not serve any party or group interest” and even its bloody-handed past was nowhere near as reprehensible as assumed.

Yes, he conceded, it was the engine of Stalin’s Great Terror, but “although many associate this period with the mass fabrication of charges, archive materials show a significant number of criminal cases were based on factual evidence.”

So that’s all right, then.

What else, though, could possibly have been expected from him? A tearful mea culpa for past horrors? An open admission that the FSB is part of a security apparatus unreservedly committed to Putin and the preservation of the current system?

Perhaps more important and more interesting was a talking point in Putin’s own speech on the anniversary. He called on the modern-day Chekists, those “true patriots and defenders of the state,” to “erect a safe barrier against foreign meddling in our social and political life,” pointing not just to radical and terrorist elements but also “foreign security agencies.”

Just as Moscow’s electoral meddling is a hot topic in the West, he was implying that nefarious external agencies had Russia’s 2018 presidential election in their sights.

Indeed, Bortnikov – who has long been one of the most xenophobic voices in Putin’s inner circle – went one further, claiming that “the destruction of Russia is still an obsession for many” foreign powers.

On one level, this is a classic ploy, casting accusations back at outsiders, sometimes with a knowing wink, to mislead the gullible and exasperate the rest. As a Russian criminal proverb has it, “confession is fit only for the priest and the fool.”

However, there is more to it than that. As old buttresses of his legitimacy crumble, from memories of the anarchic 1990s to discernible improvements in living standards, Putin wants to replace them with the time-worn appeal of “Russia beleaguered.”

It is hard to sustain a serious claim that NATO tanks are about to surge eastwards – though some of the Kremlin’s more fanciful propagandists do try – but the virtues of the “secret battlefield” of intelligence work is that it is precisely covert.

Appealing to largely-mythical claims of foreign subversion performs two useful functions. First of all, it plays to this fantasy that the Motherland is in danger. At such a time, the Kremlin’s line will be: it is foolish, dangerous, even unpatriotic to consider changing the helmsman. Safety first is likely to be a key message of Putin’s re-election campaign.

Secondly, it implicitly smears opposition candidates, and especially the shadow candidate Alexei Navalny. They are, at best, naive dupes of the pernicious Western “special services,” at worst, willing quislings.

These are, of course, all classic elements of the Kremlin playbook, products of a lack of imagination and a habitual reliance on mythical security threats to justify every piece of idiocy, malfeasance and repression. How well they will play with a public that has seen it many times before remains to be seen.

It also may throw up some of the tensions within the security apparatus. Bortnikov has more than usual reason to talk up the probity and vale of the FSB, because it faces a challenge from the new kids on the block, the National Guard.

Having been founded as a public order force, the Rosgvardiya is now agitating to be allowed to establish its own intelligence and analysis arms. In doing so, it is mounting a direct challenge to the FSB, which is itself seeking to cherry-pick effective control over the more politically-important and lucrative elements of the Internal Ministry.

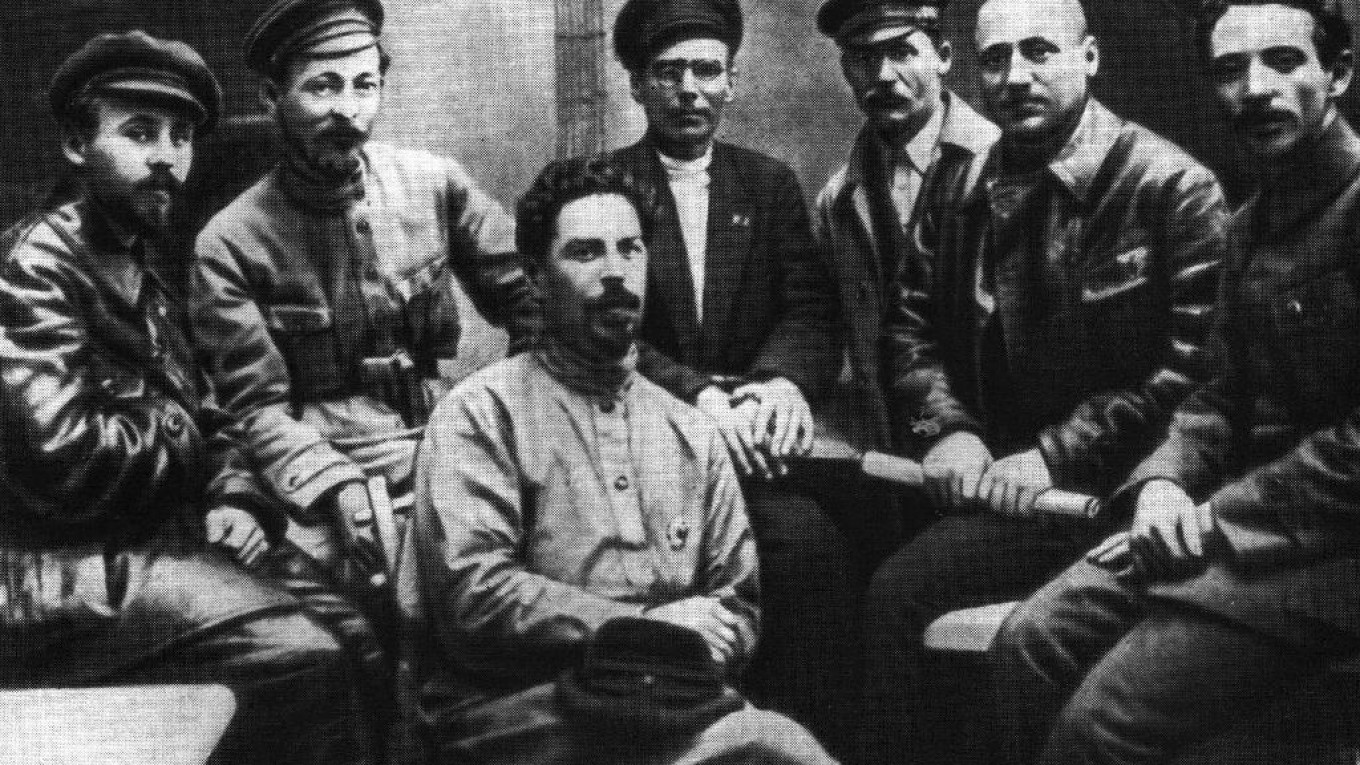

‘Iron Felix’ Dzerzhinsky, founder and head of the Cheka, did not have to deal with any of these frustrating complexities of electoral politics and rival agencies. While eulogising his creation, Bortnikov may well be envying his circumstances.

Mark Galeotti is a senior researcher at the Institute of International Relations Prague and coordinator of its Center for European Security. The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.