Not so long ago, the migrant population of Chelobityevo in northern Moscow lived in fear of the police. These were times when uniformed officers would descend on the village unannounced, beating and arresting undocumented workers in their path. Once, migrants were forced to strip naked in freezing winter temperatures, their clothes then tossed onto a bonfire. More commonly, the police would confiscate cash or make the migrants their personal slaves — putting them to work in police stations or even at officers’ own homes.

The local Russian population wasn’t much better. While happy to rent spare rooms, basements, and sheds to the laborers, they resented the migrants and the shanty town they built on the outskirts of town. The locals expressed particular anger over a hostel for foreign workers constructed from stacked shipping containers. There, in a letter to a local news site, they claimed migrants were living in unsanitary conditions, that criminals sold drugs openly, and that the hostel management hired local children to keep a lookout for police.

As tensions surrounding labor migration reached a fever pitch in the late 2000s, Chelobityevo’s divided population became an infamous case of social discord. Today, the shipping container hostel remains, but Chelobityevo has a different feel. With the country sinking into decline, the migrant labour force, previously at the forefront of economic change, is itself transforming. Many have decided to head home; others are being squeezed out by new labor laws.

The hostel has decided even to change its business model, with a new focus on internal Russian migrants arriving from provincial towns. “This is what the director decided,” says Takhmina, a Tajik woman who lives and works in the hostel. “It’s easier this way, and there are fewer problems with the authorities.”

Next door at another hostel, an elderly Tajik woman waves reporters from The Moscow Times toward the exit, where a poster warns residents not to open the door for migration officers. “Almost everyone has gone home now that there’s no more work,” she says.

A Changing Country

Since the early 2000s, unemployment and poverty have driven millions of people from post-Soviet countries to seek work in the booming Russian economy. In cities across Russia, they toiled at construction sites, sold goods at markets, and swept the streets—all with the goal of sending money home to their families. Central Asians entered the labor force in particularly large numbers, and, today, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are likely the two most remittance-dependent countries in the world.

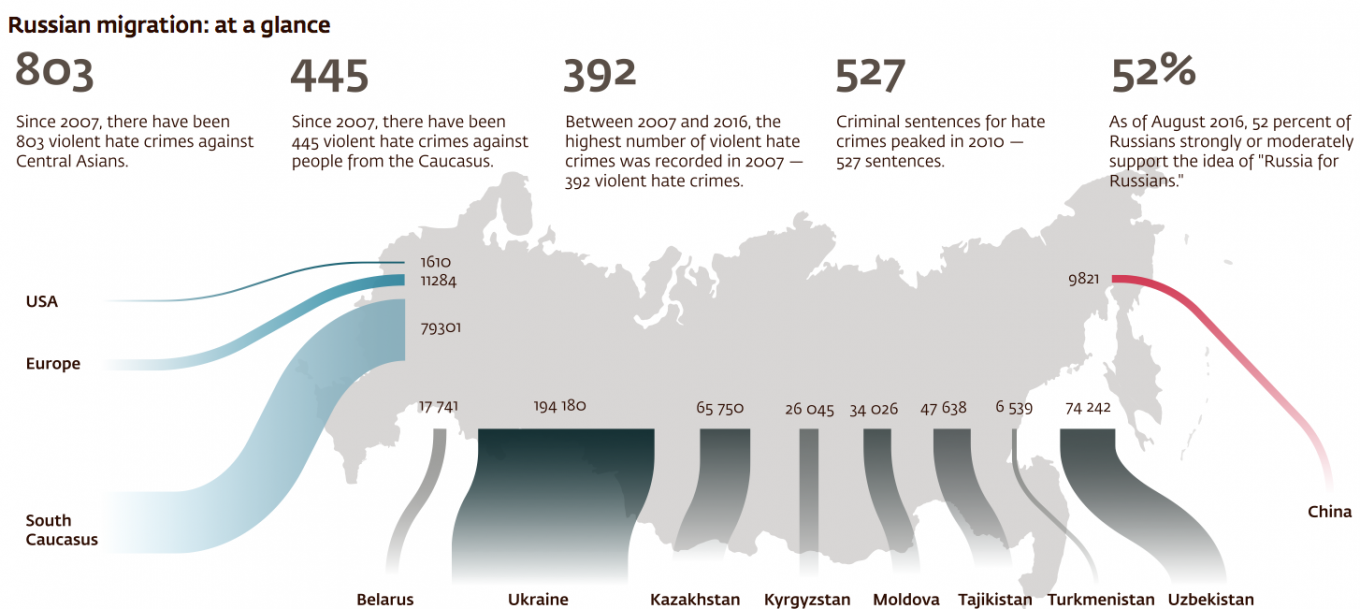

But integrating foreign laborers has been far from smooth. Many Russians resent the migrants’ cultural differences and poor command of Russian. Politicians—both pro-government and opposition—have attempted to harness anti-migrant sentiment to promote their own careers. In 2013, up to 1,000 Muscovites rioted through the depressed Biryulyovo neighborhood in southern Moscow shouting “Russia for Russians” and “white power” in response to a murder committed by an Azerbaijani immigrant.

“Families collapse, children are left without parents, migrants suffer at the hands of skinheads." Read more.

Ironically, Russia’s plunge into poverty has given these crowds what they wanted. As a result of falling oil prices, which have drastically weakened the Russian ruble, work in Russia is now much less profitable. As a result, the number of foreign laborers has decreased—perhaps by 20-25 percent, according to Sergei Abashin, an anthropologist who studies labor migrants in Russia.

Meanwhile, adjustments to migration laws have had a similar effect, pushing migrants out of the country. Starting in 2015, the Russian government has only required labor migrants to purchase a special patent to work in Russia. On the surface, this new, simplified requirement has made it easier for post-Soviet labor migrants to legally work in the country. But the elevated cost of the patent has imposed “a very large burden on migrants, especially during an economic crisis,” Abashin says. Additionally, migrants must now pass an exam proving a basic knowledge of the Russian language and the country’s laws and history.

Russia has also streamlined the processes for keeping migrants out. Deportations have increased, and, in 2013, Russia established a comprehensive electronic migration database. The border service is now able to enforce a strict law denying entry to individuals who have committed more than two administrative offenses—including traffic tickets and housing registration violations—within three years.

The result is that many migrants arriving back at Sheremetyevo Airport after a visit home discover that they have been automatically denied entry for a period of up to ten years.

“It’s a kind of deportation by stealth,” says Madeleine Reeves, an anthropologist and migration specialist at the University of Manchester. “There has been a real increase in the severity of how the law is being implemented, especially in terms of re-entry.”

Svetlana Gannushkina, chair of the Civic Assistance NGO, believes all these developments have “quieted the nightmare” that was Chelobityevo, but she hardly considers them positive. The “two administrative offenses” standard is an overly blunt instrument, she says.

Getting one’s name removed from the database is nearly impossible—even going to court is no guarantee. “The courts spend just four minutes deliberating on a deportation case,” says Gannushkina. “They often don’t call for translators, meaning that people don’t understand what they’ve signed.”

Room for Hope

It is unclear which development—economic crisis or changing laws—has had a larger effect on migration. But the cumulative effect is clear: fewer migrants are coming to Russia and more are leaving.

Azim Makhsumov, a Tajik national who works with migrants at the Ryazan-based NGO “We Are Different, We Are One,” says it is the best skilled labor migrants—the ones who made up to $1000 a month—who leave first. When the economic crisis eroded their pay, many realized that they could earn a comparable income in their native countries.

Migrants who never commanded such high salaries are often the ones now attempting to weather the crisis. But they can hardly manage to send money home.

However, not all the developments are negative. Over the years, there has been a clear increase in the number of migrants moving to Russia with their families. In Ryazan, Makhsumov has watched the Tajik community grow, and now many Tajik children study in the local schools. Some Tajik men are marrying Russian women and mixed families are emerging.

Since the West imposed sanctions on Russia, Makhsumov has also noticed that “negative attention” toward migrants has decreased. On a day-to-day level, he believes relations have improved. According to data from Moscow’s Sova anti-extremism center, he may be onto something. Since their peak in 2007-2008, hate crimes against people from Central Asia and the Caucasus have consistently fallen, with the exception of a brief uptick in 2013.

Perhaps most encouragingly for Makhsumov, the number of Tajik citizens studying in Ryazan’s universities has increased from around 25 people five years ago to more than 100 today.

“These are people who came here, worked for a few years to save up some money, and used it to get an education,” Makhsumov says.

Such gradual assimilation does not surprise Abashin. He emphasizes that public concern about migration usually focuses on temporary migrants — often young men — and the places where they live in large numbers: construction sites, markets, dormitories, and far-flung neighborhoods under active development. By contrast, immigrants, a growing minority of Central Asian diasporas in Russia, tend to avoid these areas and integrate more rapidly into daily life in the places where they live. “Of course, there is still xenophobia,” Abashin says, “but without the previous fear and conflict.”

This distinction is especially noticeable in Chelobityevo. Just a few years ago, the village was defined by temporary migration and interethnic hostility. Today, Central Asians are still a visible presence in the town, but many are now individuals with permanent professions: shopkeepers and auto mechanics, for example. The number of temporary workers has decreased.

Now, it is difficult for Takhmina, the hostel worker, to imagine the scenes of police brutality that previously characterized the community.

“The police used to come here frequently,” she says, shrugging her shoulders, “but I haven’t seen anything happen while I’ve been here.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.