All regimes change, whether they evolve or decay, rise or fall. Authoritarian regimes have a tendency to move from dynamic, populist, revolutionary beginnings through consolidation and ultimately hidebound conservatism, much like the leaders themselves. Autocrats in particular often become increasingly disconnected from their own people and the world, the comforting half-truths of courtiers blurring and rose-tinting the realities of the day, propaganda and witch-hunts replacing for genuine ideological commitment and popular enthusiasm.

One would be tempted to suggest that the ‘Trump Revolution’ has charted this course in record time…

Putin’s path

In this context, it is clear that Putin’s regime has passed through a series of distinct stages. ‘Optimistic Putin’ in his early presidency was committed to restoring the meaningful power of the centre and the government, reversing its admittedly dangerous decay under Yeltsin, when Russia became not a failed, but maybe failing state. He talked tough on national interests but was distinctly pragmatic, seeing some kind of positive relationship with the West as both necessary and achievable. Rather, his targets were the oligarchs – symbolically broken with Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s arrest in 2003 – and the general decentralisation of power.

His consolidation of that power coincided with a growing dissatisfaction with the West, a belief – justified or (often) not – that it was taking him and Russia for granted. His fiery speech to the Munich Security Conference in 2007, in which he warned of a ‘world in which there is one master, one sovereign’ as ‘the United States has overstepped its national borders in every way… in the economic, political, cultural and educational policies it imposes on other nations’ reflected this growing disenchantment, one mutually shared by the West.

His second stage was thus perhaps ‘Putin Disillusioned,’ as he internalised these clashes not as the results of a mismatch between his expectations as to how the West would treat Russia and the reality, but as evidence of its hypocrisy and hostility. This was the era when spending on social programmes and security alike bought both power and popularity, and his model seemed not so much a Russia integrated with the West, nor yet one openly at odds with it, but a nation that could stand alone.

The interregnal period of 2008-12, when Putin bided his time as the unhumble servant to President Medvedev, was many things. It was an extended audition for Medvedev as a potential successor, one Putin clearly decided he had failed. It was a period of limited experimentation with liberal reform, or perhaps of competing strategies in the political marketplace. But it was also a period in which a new stage of Putinism was evolving, one seemingly based more on an ideological commitment to ‘making Russia great again’ and a personal one to securing Putin’s legacy and his place in history.

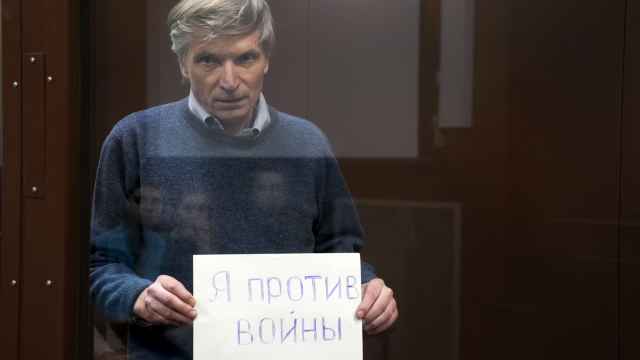

Combined with the shock that was the massive Bolotnaya protests, which seems to have persuaded him that there was a strata of the Russian people who were either insufficiently loyal or excessively susceptible to the siren song of ‘Westernisation', this seems to have pushed Putin into his current phase, one dominated by defensiveness, to the point of kneejerk aggressiveness.

Late as in last

Why call it ‘Late Putinism’ rather than stage four, or ‘Nationalist Putin’ or simply the current stage? It is not simply because Putin is now 66, not 47 as when he was first elected, nor yet because the constitution bars him from re-election when his current term ends in 2024. He is, after all, still a stripling compared with King Salman of Saudi Arabia (83) and Donald Trump (72), and Italy’s indefatigably perma-tanned Silvio Berlusconi (82) seems unwilling to slow down.

Nor can the constraints of the constitution be considered a serious impediment. After all, while Putin has an interesting commitment to the letter of the law, there are all kinds of ways its spirit can be warped, from another presidential-prime ministerial swap as in 2008-12, to the creation of some new position to which Putin could jump.

Rather, the reason for considering this the late – as in last – phase of Putin’s personal evolution is precisely that there seems not to be the will, capacity and interest in any further growth and change.

Here is the irony, at the very time that excited Western pundits and politicians have been spying Putin’s dark influence in everything from populism to football hooliganism, while they portray Russia as deploying some fiendish ‘new way of war', the truth is that the regime is increasingly brittle.

It has demonstrated a distinct lack of capacity to adapt, proven out of touch with the emerging social, cultural, economic, political and technological realities.

Of course, this is a bit of a cliché and a caricature, but one rooted in a reality. Witness the incomprehension of rap (or TV propagandist Dmitry Kiselev’s embarrassing attempt at its appropriation, akin to watching dad try and break-dance), the evident discomfort with the internet and its associated realities, from instant messaging to cryptocurrencies, the cultural disconnect that has emerged not just between the Kremlin and its subjects, but also Moscow and the regions and an older generation who remember Soviet times and the anarchy of the 1990s and one for whom these are the subject of oral history and competing mythologies rather than personal experience.

The dying of the light

By extension, late Putinism is likely the last stage of Putinism. This is not necessarily senescent Putinism, because one can still see power and purpose at times in the Kremlin's actions. Besides, there are still politicians and technocrats doing their bit, like the generals and administrators who fought to hold the Roman Empire together even while fragmentation, corruption and decadence were hastening its doom. Elvira Nabiullina's Central Bank is continuing to try and cleanse the system of toxic banks, Sergei Shoigu's military continues to arm and train to considerable effect, the economic oversight exerted by Maxim Oreshkin ensure that the worst Russia faces is sluggishness, not stagflation. There are propagandists still able to mobilise ‘hipster nationalism', and security officers vigilantly cracking down whenever they see a threat.

But the whole is less than the sum of its parts. Absent any clear, compelling and above all credible strategy, beyond the ringing declarations about the importance of diversification and Putin’s ‘May Decrees’ and ‘National Projects’ – which have all the hollow bombast of 1970s Five-Year Plans – there is a vacuum at the heart of current policy. Technological and economic breakthroughs – which cannot be denied – take place as much as anything else in spite of the government, not least its failure to maintain rule of law and thus real and intellectual property rights, as thanks to it.

Meanwhile, the political foundations of the regime decay. Putin’s approval rating is at a ‘mere’ 60-or-so percent, which is admittedly close to his previous low of 59% in 2013, but even according to the government’s VTsIOM pollsters, trust in him is now 33.4%, the lowest level since 2006 and down from 71% in 2015. Strikes and 'under-the-radar’ grassroots civil activism proliferate, and elite struggles over resources and precedence become increasingly evident.

Of course, this is still a regime that understands power. Although Alexei Navalny’s recent expose of National Guard chief and Putin attack dog Viktor Zolotov’s alleged embezzlement represented an interesting new front as he tries to undermine the Kremlin’s monopoly of coercion, at present there is no serious threat to Putin and his cronies. But what does it say about the new mood of the elite that the Duma is now looking to criminalise ‘disrespecting the government’? That hardly suggests confidence and optimism.

Absent new ideas, with nothing visible on the horizon beyond economic sluggishness and popular disgruntlement, this becomes rule for its own sake, a rigor mortis regime’s dead hand gripping the reins.

After all, there is another way of interpreting ‘late Putinism’ – as in dead Putinism. Only in hindsight will we really be able to know for sure if this regime, for all its apparent activity, is dead or only resting.

Mark Galeotti is a senior associate fellow of RUSI and senior non-resident fellow at the Institute of International Relations Prague, as well as a 2018-19 Jean Monnet Fellow at the European University Institute. His most recent book is “The Very: Russia’s Super Mafia”. This article was originally published in Raam op Rusland.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.