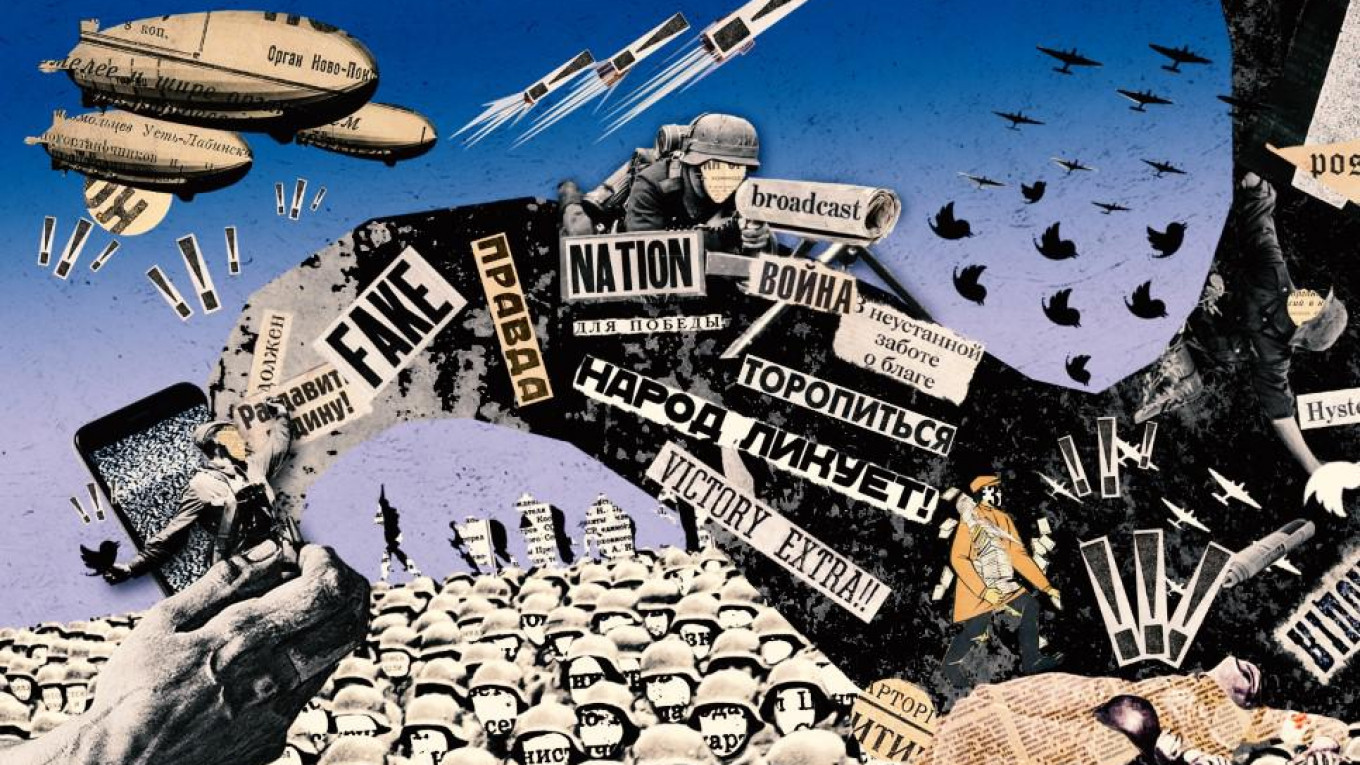

“Psychological warfare has existed as long as man himself.”

So begins a book purported to be an unauthorized reprint of the Russian military intelligence service’s (GRU) textbook on psychological warfare. The book was published in Minsk in 1999. But it has long been the basis of courses on psychological warfare for reserve officer training (ROTC) cadets at Moscow State University’s (MGU) journalism faculty, former students say.

“In the past people were able to influence each other only through direct contact,” the textbook reads. “Today, the means of influencing the human mind have become much more sophisticated, thanks to the accumulated knowledge of thousands of years, information technologies, communication, and management.”

While the purported GRU textbook was ahead of its time, several graduates of the MGU classes described lessons as archaic. The scale of the information space has grown since 1999, and control over it has become more critical to modern war. And now, Russia appears to be upgrading its efforts to dominate the information front.

On Feb. 22, the eve of Russia’s annual Defenders of the Fatherland holiday, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced the creation of a new “information operations force.” The announcement came just hours after the Foreign Ministry unveiled a new project to expose “fake news” published about Russia in the Western press.

“Propaganda needs to be smart, competent and effective,” Shoigu said, justifying the creation of a force capable of waging information war.

Shoigu’s comments regarding new information operations were vague, leaving it unclear exactly what the propaganda troops would do or who they would report to. Experts say they are likely to be part of the cyber forces — a military branch announced in 2013, but that Russian officials have since denied exists.

“They seem to be cyber troops [hackers], not information war troops [propagandists],” says Michael Kofman, a Russia security analyst at the Virginia-based CNA think tank. “The Russian military already has psychological operations units, but they are all useless. It’s the GRU that does all the real information war.”

Others suggest that the force will do both hacking and propaganda. Russia’s understanding of what constitutes information war is much broader than the West’s, says Mark Galeotti, an expert on Russian security and defense services at the Institute of International Relations Prague. For Moscow, “information operations” include everything from propaganda and disinformation to psychological and cyber warfare.

“Things we tend to compartmentalize (and label with weasel expressions such as ‘strategic communications’) are to the Russians all part of one seamless domain relating to the human, morale-and-will side of warfare,” Galeotti says. Shoigu emphasized propaganda, a word that has a far less negative connotation in Russia, “but that is only part of the force’s true remit.”

New Dog, Old Tricks

Vladimir Shamanov, the head of the State Duma’s defense committee, offered some insight into how the Russians see the new military force. It will be tasked with, among other things, countering information operations conducted by enemy states. “Information conflict is part of general conflict,” he said.

Despite flashy repackaging, the militarization of information is not new in Russia. Psychological warfare has been a staple of Russian ROTC programs since the Cold War. It is also taught as a military science in the journalism faculties of major educational institutions such as Moscow State University.

“My rank after graduating [from the course] in the early 2000s was lieutenant and I was a deputy division chief of staff for intelligence,” says Dmitry, a former officer who's name has been changed to protect his anonymity. “It guaranteed I wouldn’t be drafted into the regular forces and sent to Chechnya. But in the case of a full-scale war [with NATO], I was to oversee psyops against their troops and civilians.”

Dmitry says that he and his fellow cadets were trained explicitly for a major conventional land war with NATO.

The purported GRU textbook that the courses are modeled on even advises different approaches to waging psychological warfare on different NATO members. So, the Germans have an “abstract-logical” way of thinking, but "prefer clearly reasoned facts and calculations,” the textbook says. "The French and Americans love visuals. The Germans also love visuals, but only those which have double meanings. While the French prefer catchy ideas, emotional expressions and loud words."

Information Operations 101

Studying the pathological moves of enemy societies is meant to help cadets tailor their approach to psychological warfare if called into action. Broadly speaking, the courses teach three types of weaponized information. Since Dmitry graduated, the program has become more secret. Current students and more recent graduates declined to comment, citing non-disclosure agreements and a general atmosphere of secrecy surrounding their training.

The first category is white propaganda — the most common and identifiable type.

White propaganda has clearly attributed source and discernible motive. For Americans, prominent examples include the broadcasts of Hanoi Hannah during the Vietnam war. The North Vietnamese propagandist was famous for her “go home G.I.” refrain, encouraging soldiers to lay down their arms by telling them their cause was unjust.

Alexander Mityaev, a 2003 ROTC graduate, gave an example of how Russians would taunt American soldiers:

“There was an old colonel who taught us how to cut the Yanks’ supply lines to starve them of their Camel cigarettes and Coca-Cola, and then shower them with leaflets mocking their inability to survive without Camels and Coke.”

Leaflets were to be distributed with what is called an agitsnaryad, a play on the Russian words for “political agitation” and “artillery shell.” These non-explosive shells would be stuffed with leaflets and fired by a howitzer beyond enemy lines. “There was a science to it: how to prevent leaflets from sticking together inside the shell, and so on,” says Mityaev, a lieutenant in Russia’s reserve forces and CEO of Moscow CityPass.

Then there is gray propaganda, defined as information that has no obvious source, and uses a mix of proven and unproven facts to promote a favorable narrative or trick the enemy into believing one thing over another. The GRU textbook cites U.S. efforts to convince the world that the Soviet Union shot down Korean Airlines Flight 007 in 1983 in cold blood as an example of this approach.

“The U.S. Information Agency immediately prepared a 5 minute film based on conversations between the Soviet Su-15 interceptor pilot and ground controllers [...] and then showed it to the UN security council,” the textbook says. “The video indicated that Major Osipovich [the Su-15 pilot] shot down the Boeing 747 with no warning, knowing it was a passenger plane.”

But the most insidious form of information warfare, according to the GRU textbook the courses are based on, is black propaganda, a false flag operation.

Dmitry recalls that one of the specific black propaganda techniques taught in his textbook. During the Chechen conflict, Russian psychological warfare experts spread rumors that foreign fighters had raped the 13-year-old daughter of a Chechen village elder. The rumors helped sow discord between Chechen fighters and Arab Islamist volunteers, undermining the unity of the rebels.

“There was a spirit of moral ambivalence to all this,” Dmitry says. “We knew what we were doing was wrong, but the ultimate truth was on our side, so it was something we just had to do.”

Neither of the psychological warfare soldiers could explain why a new information operations force was necessary. After all, they argued, the military already has the means to do what it wants, and existing Russian propaganda outlets and troll factories do the disinformation job just fine.

“Maybe Shoigu just wants another plaything,” Dmitry says.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.