Commentators have already compared President Vladimir Putin's recent address before the UN General Assembly with his speech at a security conference in Munich in 2007. Some, such as Sergei Markov, claimed the speech was "tougher than Munich, outright anti-American," while others, such as Tatyana Stanovaya, argued that it was "the opposite of Munich," an effort to return to the time in 2001-03 when Russia was not a rival of the West, but an ally.

"Munich II" or the "anti-Munich," that is the question. The answer lies in a simple comparison of the two speeches. In Munich, Putin used the words "unipolar" or "unipolar world" five times, "NATO" seven times, "confrontation" twice, "provoked" once and "so-called" two times. In his speech before the UN General Assembly, in place of the term "unipolar," Putin spoke of "bloc mentality" and "the only center of dominance." At the same time, he mentioned "egoism" twice, "ambition" four times, "confrontation" twice, "manipulate" twice, "provoked" once, "so-called" once and "hypocritical and irresponsible" once.

In 2007 Putin addressed the West, saying: "There is no need to play God and solve all of these peoples' problems." And in 2015 he asked: "Do you at least realize now what you've done?" And concluded: "But I'm afraid that this question will remain unanswered, because they have never abandoned their policy, which is based on arrogance, exceptionalism and impunity."

This simple comparison clearly shows that Putin's UN address is in no way the opposite of his Munich speech or an appeal for peace. Although the call for cooperation made his UN speech somewhat less aggressive, his words were no less stern than in Munich. The Kremlin is trying to revive cooperation with the West — frozen over the conflict in Ukraine — without making any concessions on its own position. Putin continues his hard-hitting rhetoric, and it was in this spirit that the West perceived it. And the fact that Russia began its bombing campaign in Syria shortly afterward only reinforced the aggressive impression that Putin's UN speech produced.

I wrote earlier in The Washington Post that the aggression of the Russian authorities, as well as the aggressive behavior of the governments of other oil-dependent states is directly linked to oil prices.

Research indicates that petrostates become more aggressive and start conflicts when oil prices rise sharply. In a study of 153 countries over a period of 50 years, political scientist Cullen Hendricks showed that oil exporting states become significantly more aggressive as compared to their nearest neighbors whenever oil prices soar. Hendricks found that when oil prices exceed $77 per barrel (at the purchasing power of the dollar in 2008), petrostates become 30 percent more aggressive than non-exporters.

Political scientist Jeff Colgan, using a database of inter-state conflicts involving military force from among 170 countries between 1945 and 2001, found that countries whose net income from oil exports accounts for 10 percent or more of gross domestic product are the most belligerent in the world. They tend to use military force in interstate conflicts, and since World War II, were 50 percent more likely than ordinary states to become involved in military conflicts.

Venezuela's mobilization for war with Colombia and Iran's support for Hezbollah's planned attack against Israel as oil prices climbed toward their peak in 2008 fully accords with this rule, as does Iraq's invasion of Iran in 1980 and Libya's repeated attacks on Chad during the sharp increases in oil prices in 1970 and 1980. "Petrocratic" states become aggressive because high oil revenues increase their military potential, leading to an increase in adventurism in the international arena.

In this sense, Russia is an ordinary petrostate. When oil was $25 per barrel in the early 2000s, Putin sought cooperation with the West and spoke of Russia possibly joining NATO. Hendricks shows that such behavior is normal for petrocracies, and that they are even more peace-loving than ordinary states when oil prices fall below $33 per barrel.

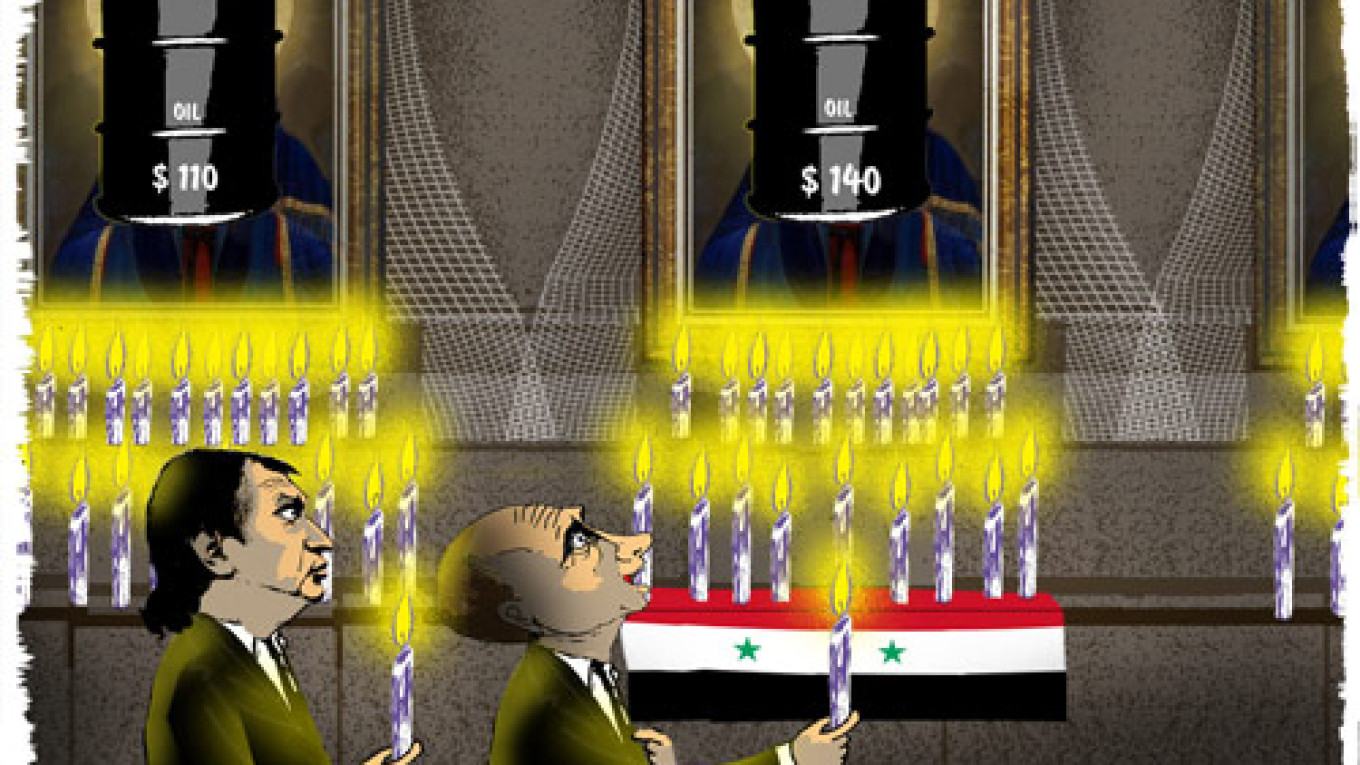

When a barrel of Urals crude cost approximately $20 in 2002, Putin set Russia's integration with Europe and the creation of a single economic space spanning Russia and the EU as priorities in his speech to the Federal Assembly. However, when the price of oil hit $110 per barrel in 2014, Putin sent his military into Ukraine to punish it for trying to create the same type of unified economic zone with the same European allies. Putin delivered his unprecedentedly aggressive speech in Munich in February 2007 at a time when oil was at $54 and rising and Russia was "getting up off its knees."

However, the Hendricks model does not explain why the Russian leadership continues to behave aggressively and make Munich-like public pronouncements even when oil prices are falling or volatile — ranging between $40 and $50 per barrel in August-October 2015.

Despite the fact that the price of oil has dropped by half in the past 12 months, Moscow's ruling elite is confident it will rebound within one to three years. Speaking at the Sochi 2015 forum, newly appointed LUKoil vice president Leonid Fedun even predicted that the price would return to $100 per barrel as soon as 2016. Rosneft president Igor Sechin is similarly optimistic.

In this regard, economist Vladislav Inozemtsev delivered a lecture in which he quoted Ivan Starikov as calling these Moscow dreamers the sect of "High Price Witnesses."Because of their almost fanatical belief, Kremlin officials consistently postpone implementing long overdue and vital reforms, advising citizens to simply tighten their belts and wait out the current crisis.

In that same lecture, Inozemtsev said, "Leaders realize that this crisis will last longer, but they believe the solution is the same. In 2009, it took eight months before rebounding oil prices helped Russia emerge from the crisis. Now it will take approximately three years," he said. Thus, the actions of the Russian authorities find motivation not so much in the current price of oil, but in their expectation that the price will soon rise to previous levels.

However, Russian officials and businessmen might base their unusual and seemingly unfounded expectation of higher oil prices not so much on any quasi-cultish belief as on inside knowledge of the Kremlin's long-term plans in Syria. Economist Andrei Illarionov suggested that Russian military operations might fail to defeat Islamic terrorists but succeed in destabilizing the Middle East and driving up the price of oil.

Although confidence in a rebound in oil prices is hardly justified, it is in keeping with the statements and actions of the Russian authorities — that is, as much as anything can make sense for people "living in a different world," as German Chancellor Angela Merkel once characterized Putin. According to this logic, and following the Hendricks model, Putin will issue an "anti-Munich" speech only when oil prices stabilize over the long term at $30 per barrel.

Maria Snegovaya is a Ph.D. student in political science at Columbia University and a columnist at Vedomosti. This article was originally published in Vedomosti.