When long-time Cuban leader Fidel Castro passed away on Nov. 25 at the age of 90, Air Force Major-General Mikhail Makaruk, vice-president of the Russo-Cuban Friendship Society, went to the Cuban Embassy to express his condolences.

He found the compound’s gate lined with flowers, candles, and messages of support for the Cuban people. And he was hardly the only one there to offer condolences.

“Ordinary people were standing in line for four hours just to express their sympathies to the Cubans,” he says.

In the course of his 47-year rule, which stretched from 1959 to 2008, Castro converted Cuba into a one-party, pro-Soviet socialist state that outlasted the Soviet Union by 25 years. His legacy has also outlived the Soviet Union — particularly among the older generation of Russians.

The reason, says Alexander Genis, a Russian-American cultural critic who co-authored a book on the Soviet 1960s, is that Castro was largely a mythical figure for Russians. During the 1960s, many Russians pinned their hopes for their own country on the success of the Cuban Revolution.

“For Soviet people in the early 1960s, Castro was never a live person or a real politician,” Genis says. “He was a metaphor for the proper socialist revolution.”

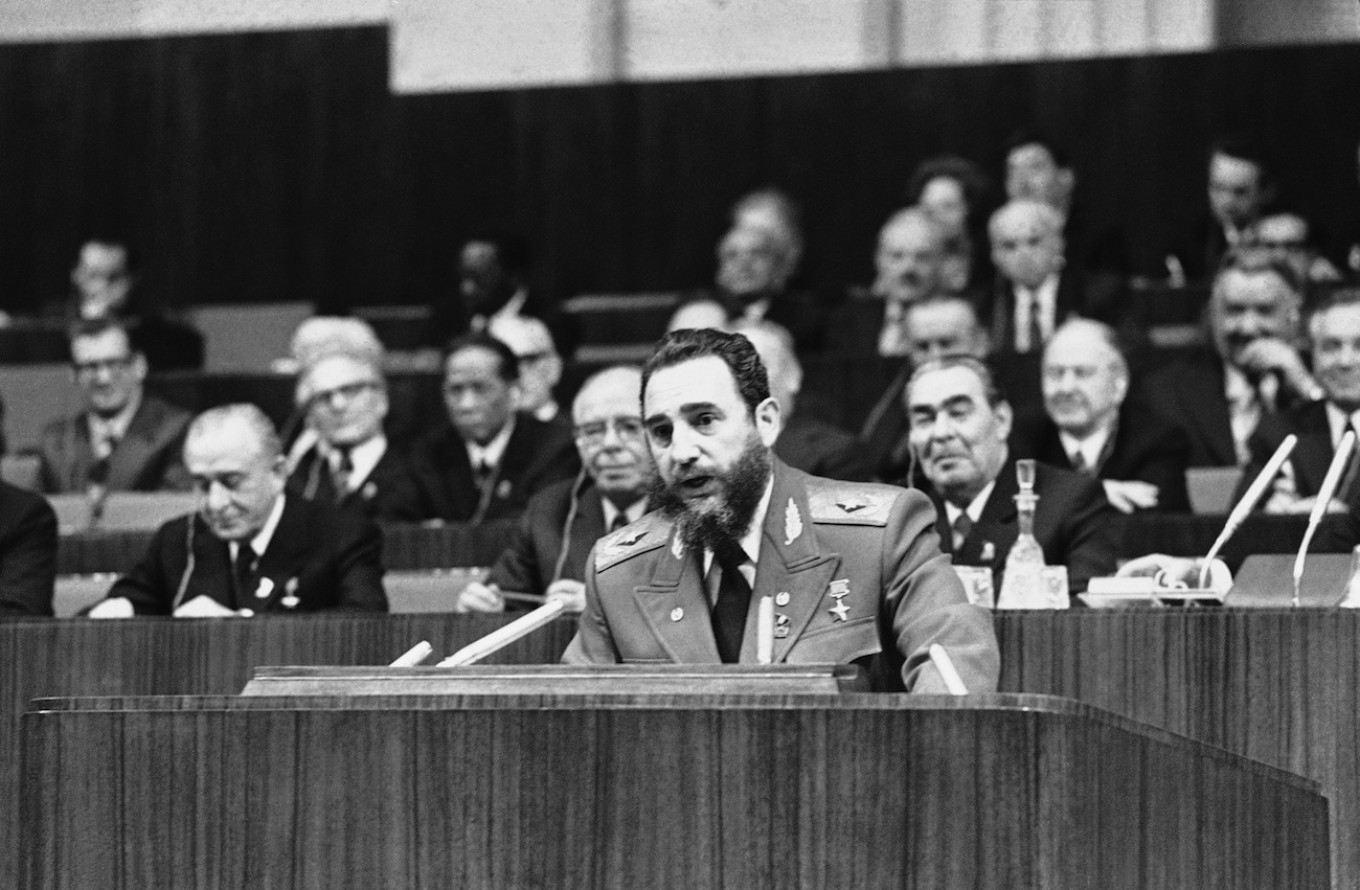

See the Photo Gallery: Looking Back on the Castro-Russia Bromance

Young Socialism

The Cuban Revolution in 1959 was undoubtedly a transformative event for Cuba. But it was also transformative for the Soviet Union. It came amid Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s Thaw, a time of increased openness when Soviet society attempted to return to the romanticism of the period after the 1917 revolution and the civil war.

Khrushchev promised that the current Soviet generation would “live under communism” and promoted the belief in a “bright future” — a standard cliché of the Soviet era. But after the ravages of Stalinism and World War II, it was difficult for many to believe in the old mythology. The Cuban Revolution — much like Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s 1961 spaceflight — represented a breakthrough for socialism.

“After the Cuban Revolution, there was a period of revolutionary romanticism,” says Nikolai Kalashnikov, deputy director of the Russian Academy of Science’s Institute of Latin America. “There was an illusion that the idea of socialism would capture the whole world. Cuba was the first country in Latin America that could resist the United States, resist the stranglehold of U.S. capital, and defeat [Cuban] dictator Fulgencio Batista.”

The Cuban revolutionaries were everything that the Soviet leadership in the early 1960s was not: young, handsome, and bearded, with guns and guitars. They lived in a tropical country where the sun always shined, unlike Russia. They embodied the hopes of the Soviet population. Cuba, it appeared, was the “bright future” the Soviet leadership promised.

Amid the cultural flourishing during the Khrushchev Thaw, Cuba came to symbolize “the Soviet person’s struggle with bureaucracy and the fight for freedom of speech,” says Genis. “People believed that there was more freedom of speech in Cuba than in Russia.”

Castro’s image as a young revolutionary and his personal magnetism made him a particularly attractive hero for many Soviet people. While a student at Moscow State University, Kalashnikov took part in a meeting with the young Cuban leader.

“Everyone met Castro with great enthusiasm,” he says. “He had enormous charisma. He could speak from his heart without reading from a text. All of this attracted people to him.”

Cuba, My Love

Many in the West associate the Cold War alliance between Moscow and Havana with the Cuban Missile Crisis, a 13- day standoff in October 1962 that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. Russians, however, often experienced Soviet-Cuban “friendship of nations” on a more personal level.

Many Soviet specialists, for example, spent time working in Cuba, giving them a personal connection with Cubans that they lacked with other “brotherly nations.” Major-General Makaruk lived for a short period in Havana at the end of the 1970s, when the Soviet Union was helping Cuba build an aviation academy. He still recalls these times with great emotion.

“Because of the [United States’ economic] embargo, there were many difficulties for the population, but their revolutionary spirit was high,” he says. “Of course, Russian specialists in Cuba lived better than the broader population, but we shared our groceries and medicines with the Cuban people.”

Although the majority of Soviet citizens

never set foot on the so-called “Island of Freedom,” a sizeable

proportion had interactions with Cuba — or, at least, with the idea of

Cuba.

Journalist Tatiana Malkina grew up in the 1970s in what she terms a “shabby mini-village on the most cast-off edge of Moscow.” In spite of this, the ordinary Soviet school she attended was an active member of the Soviet-Cuban Friendship Society. At various times during the school year, the children would read magazines about Cuba, sing songs about Cuba, study stories about the Cuban revolution, and write protest posters in support of Castro and Che Guevara.

“Of course, we all wanted to go there because of the famous Varadero [resort town], the beach, the bananas and the coconuts,” Malkina says. “There were also rumors that, in Cuba, they had chewing gum. We didn’t have gum.”

“One day some Cuban children came to visit our school. They gave us gum and danced in a way totally unlike us — it was very beautiful!” she recalls. “They were different, lively, and quite pleasant. But we looked at them almost as if in a zoo.”

Cuba even influenced the musical culture of the 1960s. One of the most popular tunes the era was “Cuba, My Love,” a song about the Cuban Revolution composed for Fidel Castro’s 1962 visit to the Siberian city of Bratsk.

That year, Iosif Kobzon, a Soviet and Russian crooner often compared to Frank Sinatra, performed the song on the musical TV program Goluboi Ogonyok in military fatigues and a beard, while holding a machine gun. He was backed by a line of gun-toting dancers dressed as Cuban revolutionaries.

Reality Bites

Since the Soviet collapse of 1991, the myth of Cuba may have lost some of its luster. This is particularly true for many Russians who have visited the country in recent years.

Malkina finally set foot in Cuba in 2002, when she went to cover President Vladimir Putin’s visit to the country to close the Russian radio intelligence station at Lourdes. The poverty she encountered in Cuba deeply saddened her. Even a visit to the famous Varadero resort could not change her mind about what she had seen.

“The sand was white, the water was blue, and the people were beautiful,” Malkina says, “but it was clear that this was a perfect illustration of the total collapse of socialism.”

“If anyone then had told me that Fidel was a great hero, I think I would have smacked them.”

Not everyone has changed their minds. On Nov. 29, Russian Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov released a statement commemorating Castro. “Cuba created a society without poor and hungry people, where each child had a right to develop his talents,” he wrote.

Many other Russians — those standing in line at the Cuban Embassy, for example — appear to agree.

“This is the most amazing thing,” says Genis. “People who have ceased to be Soviet are mourning for Castro as the myth of their youth.”