An hour after polling stations closed in Moscow on Sept. 18, Dmitry Gudkov, 36, still believed he could win, and somehow, miraculously, hang on to his seat in the State Duma.

Gudkov was running as a single-constituency candidate for liberal opposition party Yabloko in Tushino, northeastern Moscow. He was up against United Russia’s notorious Gennady Onishchenko, the Kremlin’s former uber-loyal sanitary chief.

“We are neck and neck,” Gudkov wrote on his Facebook page. “The outcome of the vote will be determined in the United States. Don’t let us down, friends.”

Gudkov was referring to Russian voters in Boston, Chicago, Miami and Washington. While the polls were closed in the motherland, the votes of Russians living in those U.S. cities could still be added to the Tushino count, and ensure Russia kept its single voice of opposition.

But the appeal to Russian voters across the Atlantic did not help. Victory soon retreated from sight, while his party was suffering an equally bad night. By 2 a.m., it became clear Yabloko was nowhere near the 5-percent threshold necessary to make it to the Duma. There would be no independent voice in this Russian parliament.

The final result, announced the next day, was overwhelming: United Russia took 343 out of the State Duma’s 450 seats, gaining a constitutional super-majority. Russia’s friendly “opposition” took the remaining seats: the Communist Party won 42 seats; nationalist-leaning LDPR won 39 seats and A Just Russia took 23 seats. Rodina and the Civic Platform won a seat each. The Duma’s only “independent” deputy is Vladimir Reznik, a man who once found himself on Interpol wanted lists and was for many years a United Russia lawmaker.

The following day, President Vladimir Putin declared his party victorious and congratulated them for the “good result.”

“How is that possible, given the economic difficulties we’ve been facing and the drop in people’s real incomes?” he said. “At times of risk, you can count on people to trust the government.”

Lowest Turnout in History

With only 48 percent of Russians taking part in the vote, this parliamentary election saw the lowest turnout in the country’s post-Soviet history.

The Kremlin was counting on this, says political analyst Alexander Kynev. It believed protest voters were most likely to stay at home, and its strategists did everything to discourage Russians from voting. Earlier this year, it moved the election from December to early autumn, meaning Russia’s campaign season coincided with Russians holidaying at their dachas.

“It was a rigged game,” says Kynev.

The result was an incredibly dull show for the electorate. With nobody doubting who the winner would be, many Russians saw no reason to bother.

Changing the Rules

The Kremlin introduced a series of safety mechanisms to secure its victory.

First, it reverted to a mixed electoral system not used since 2003. In the previous parliamentary election, in 2011, all of the Duma’s 450 seats were chosen through party lists. But this format proved ineffective for United Russia, which barely won a simple majority of 226 in 2011.

This year, Russians elected only half of the Duma deputies through party lists. The other half was elected via single-constituencies, which means a district is represented by whichever candidate receives the most votes. While the system was billed as more democratic, it would also be responsible for skewing the vote in favor of the frontrunner United Russia. With the new voting procedure in place, Putin’s party would win a majority no matter what.

“They were going to win it either way,” says political analyst Abbas Gallyamov. United Russia won 90 percent of the seats elected in the districts.

The Kremlin’s other major success was persuading voters that this election would be honest and open. “This was a big victory,” says Gallyamov.

Compared to the mass rigging observed in 2011, this election appeared cleaner. With some well-publicized exceptions, there were few major violations observed in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Russia’s Central Election Commission chief Ella Pamfilova, who staked her career on a clean election, declared the 2016 vote to be completely legitimate.

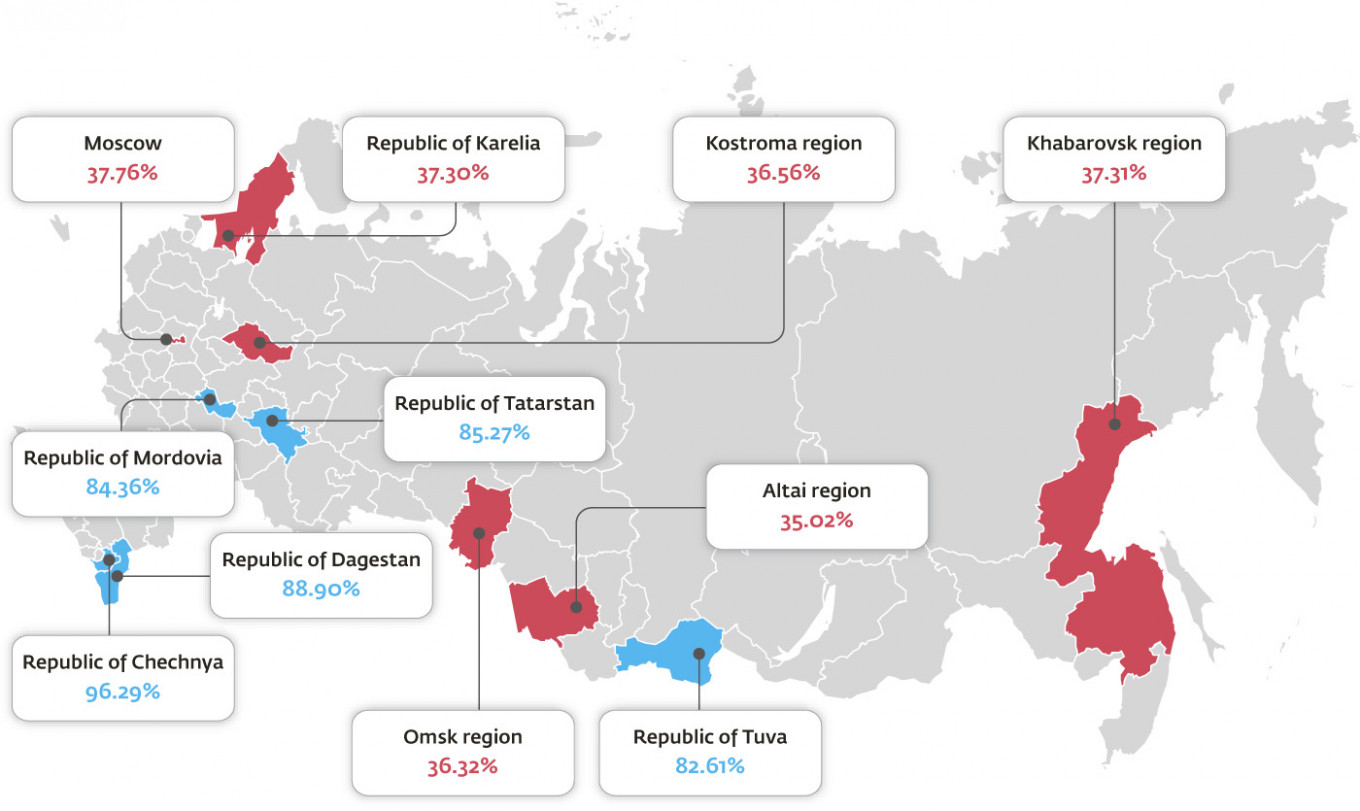

But evidence of tampering with the vote soon started to mount. Renowned physicist Sergei Shpilkin produced his own analysis of the election result, based on expected statistical distributions. His data suggested that almost 45 percent of all votes recorded for United Russia may have been falsified.

Shpilkin’s research indicated that the real turnout was likely just 37 percent — 11 percent (or 5.7 million votes) lower than what Russian officials claim. If the physicist is correct, United Russia’s share of the electorate falls from 54 percent to 40 percent.

“By my estimate, the scope of the falsification in favor of United Russia in these elections amounted to approximately 12 million votes,” he said.

No Opposition

Russia’s liberal opposition offered no competition for United Russia or regime-friendly “opposition” parties.

Neither Yabloko, led by Yeltsin-era politician Grigory Yavlinsky, nor the even less popular Parnas, led by former Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov, gained the necessary 5 percent of the vote to enter parliament. Nor did they pass the 3-percent threshold needed to qualify for federal funding. As a result, neither party will be able to put forward candidates in future elections without going through the tiresome and obstacle-riddled process of gathering signatures.

“I want to say that I am sorry,” Yabloko’s Lev Schlosberg said during a broadcast on Russia’s independent Dozhd television station late on election night. “We couldn’t get through this iron curtain to our voters. We failed to engage our voters in discussion. They don’t believe in elections anymore, and they stayed at home. This is our fault, and our responsibility.”

Most of the protest voters in the big cities, which usually supply the opposition with votes and political force, did indeed stay at home. In major urban centers like Moscow and St. Petersburg, voter turnout was the lowest seen in a decade. The progressive, middle-class electorate simply did not show up. “Think of it in terms of a general strike,” says sociologist Ella Paneyakh.

As a result, opposition-minded Russians now have no one to represent them. Indeed, newcomers in the Duma appear to be even more conservative and inclined to tighten the screws.

The most notorious among them is Vitaly Milonov, a former St. Petersburg lawmaker known for his anti-LGBT campaigns. Milonov, a member of United Russia, lobbied for the first ever “gay propaganda law” in Russia. It was passed by the St. Petersburg parliament in 2012 and approved by the State Duma the following year. Among his other infamous initiatives, Milonov has attempted to ban abortion, create a “morality police” and rid Russian schools of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Another flamboyant new deputy is Gennady Onishchenko, the former head of consumer rights watchdog Rospotrebnadzor, who won the race against Gudkov. He rose to fame for his vigilant guard of Russians’ health, which more often than not coincided with Russia’s foreign policy interests; there were import bans on Moldovan and Georgian wine, and later Belorussian and Lithuanian dairy. Onishchenko even proposed to ban condoms and cigarettes, but, luckily for many Russians, to no avail.

The new Duma’s conservative warriors will count a woman, Natalya Poklonskaya, amongst their ranks. She is famous for her good looks and infamous for her idiosyncratic nationalism and role in Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Russia’s youngest female general is the subject of numerous anime cartoons, as well as songs and online games.

Subordinate Democracy

In a column for the liberal Slon magazine, political analyst Grigory Golosov wrote that the Kremlin’s strategy was to widen the gap between those Russians who are relatively independent from the government — and, therefore, could vote for the opposition — and the elections.

“For these social groups, the strategy was to make sure that going to the dacha [instead of voting] was the priority,” Golosov wrote.

The new Duma is the last brick in the construction of a new political system, which has changed dramatically from the so-called “managed democracy” in the last four years. With the Duma now wholly subordinate, the Kremlin can do as it pleases.

But the substance of that last brick, the nation’s indifference toward politics, which the Kremlin tried so hard to achieve, may well turn into a problem as Putin starts to prepare for his own re-election in 2018.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.