"Our grandfathers built the Baikalo-Amur Siberian Mainline. So we are going to build the bridge," says a promotional videoclip on the website devoted to construction of the Kerch bridge.

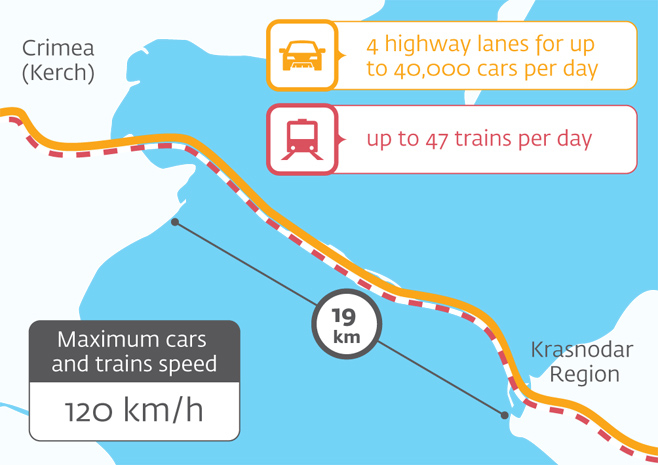

Nineteen kilometers long, the dual road-rail bridge is set to connect Crimea with the Krasnodar region, making the disputed peninsula accessible by car and train directly from Russia. The long-awaited transport miracle is scheduled for completion in 2018.

Comparisons with the grandeur of the Baikalo-Amur Mainline, a gigantic construction project from Soviet times, are in line with how President Vladimir Putin sees the new Kerch bridge — something to land him in history textbooks.

However, the very ambitiousness of the project has meant it has come accompanied by doubts and debate. From the very beginning, the project seemed too expensive, too complicated, too unnecessary, and likely to fail. Earlier this month, the first alarm bell rang, as reports surfaced that construction companies that work on the bridge and belong to Putin's closest ally Arkady Rotenberg stopped receiving necessary state funding.

Kremlin officials, of course, were quick to deem the troubles temporary and bureaucratic in nature, and that nothing threatened the project. Indeed, for Putin it is — just like the Sochi Olympics — too big to fail, and experts and commentators agree that the bridge will be built after all. The question is when and at what cost.

Kerch bridge transport capacity

Centuries of Planning

The idea to build a bridge across the Kerch Strait first emerged in 1870, when the British built a telephone line traversing the strait to connect with India. The line worked so well initially that they contemplated adding a railroad bridge over it. But when it came down to the cash, building was deemed too expensive.

Later, Tsar Nicholas II also considered the idea, but had to shelve it at the start of World War I.

The first attempts to actually build the bridge were made by Nazi Germany in the 1940s. With German troops already in Crimea, the bridge was to be a key infrastructural support of a Nazi push on the rest of the Soviet Union. Adolf Hitler's personal architect and trusted minister, Albert Speer, was put in charge.

Soon after construction began, however, Soviet troops began to push the Nazis back. Retreating, the Germans tried to destroy what they had managed to build. Using what remained, the Soviets managed to complete a bridge in 1944.

Then, it was a railroad bridge, and the governmental delegation headed by Josef Stalin used it to return to Moscow from the Yalta peace conference. However, it had been constructed using wooden supports, and heavy ice flows damaged it in 1945. Rather than repair it, the decision was made to dismantle the bridge, and, in 1954, a ferry crossing was launched between the Crimean town of Kerch and the town of Taman in southern Russia.

The ferry service continues to this day, but the idea of bridging the strait has regularly resurfaced.

In the early 2000s, it was brought up by then-mayor of Moscow, the infamous Yury Luzhkov, who had been publicly supporting and funding different initiatives in Sevastopol, the capital of Crimea and Moscow's "sister city."

In 2001, Luzhkov met with Crimean officials in the Krasnodar region. He promised that Moscow would invest $100 million in building a bridge. In 2008, Russia and Ukraine reached a formal agreement to span the strait. But the expensive project kept stalling, and was overtaken by events in early 2014.

After Russia's annexation of Crimea in March 2014, the peninsula found itself between a rock and a hard place. Its railroads and highways, not to mention its water, electricity and gas, were all dependent on Ukraine. First, these arteries were limited by the Ukrainian government; and later partly severed by pro-Ukrainian activists, tacitly supported by Kiev.

Meanwhile, Russian tourists looking to holiday in Crimea in the summer had to stand in line for the ferry for several days. With outrage over the transportation collapse on the peninsula growing, the Kremlin's decision to build the bridge seemed politically astute.

The Kerch bridge will provide a direct link between the Krasnodar region and Crimea.

Putin's Friends

At first, Russian authorities hoped to involve foreign investors and construction companies. Not only would their participation have eased the financial burden — construction costs at the time were estimated at more than $5 billion — but it would have also served as an acknowledgement that Crimea was part of Russia, government sources told Forbes magazine. However, with the conflict in eastern Ukraine unfolding, sanctions mounting and Russia moving away from the West, foreign interest in the project faded.

Among Russian businessmen, Arkady Rotenberg and Gennady Timchenko, Putin's closest associates, were considered the most likely candidates to take on the project. But Timchenko soon folded and publicly refused to participate in the construction of the century, citing the project being too complicated and carrying "major reputation risks." The project went to Rotenberg.

In reality, the Kremlin didn't have much choice in who could be awarded the project, says political analyst Yekaterina Schulmann. "Because of sanctions and political pressure, there weren't many people inclined to become involved in something like this."

Rotenberg's peculiar political position, however, allowed him to undertake this project. Already under sanctions, the businessman was not allowed to enter the United States or the EU, and his foreign assets had been frozen. "Rotenberg could show readiness to take on major projects important for the country. Who else would have fallen on the sword like that?" Schulmann told The Moscow Times.

Construction is best carried out in the summer months when the water is warm and the re are more daylight hours in which to work.

Obstacles Ahead

In the two years since Rotenberg won the bid, the cost of construction has dropped significantly, aided by the ruble devaluation, but still remains over 200 billion rubles ($3.4 billion). The future bridge would be unique in Russia from an engineering point of view, says Sergei Zege, bridge engineer from the Moscow Automobile and Road Construction Institute. Several inevitable complications mean its rapidly approaching deadline might not be met.

First, the Kerch Strait is an extremely difficult location for construction. Its geological condition, high seismic activity and adverse weather add complications to the building process. The layer of silt on the bottom of the strait is thick, which means piles needs to be driven deep into the ground — sometimes to depths of up to 90 meters. It is difficult to predict how deep a pile must go, says Zege, because the thickness of the silt layer varies.

Most piles must be installed before winter, the engineer says: During cold months, it will be that much more difficult to work. "It's one thing to do it now, when the water is warm, there are 14-15 hours hours of daylight and there are no ice flows," Zege says.

Between November and March, there is also a strong possibility of storm winds, says Viktor Galas, deputy director of "Institute Giprostroimost — St. Petersburg," a company involved in the construction. "Delivering necessary materials to the site, as well as using construction equipment, becomes difficult," he told The Moscow Times.

Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Kozak look at a Kerch bridge construction model at the 2015 Sochi Forum.

In order to minimize the influence of the weather, several temporary, technical bridges are being built, Galas says: They will allow for building to commence on the bridge in eight different spots simultaneously. In addition, three meteorological stations are already functioning in the area, says Leonid Ryzhenkin, department head at Stroigazmontazh, the Rotenberg company that won the bridge bid. "The accurate weather forecasts received from these stations allow us to foresee storms and modify our schedule," Ryzhenkin told The Moscow Times.

Another potential obstacle is legal in nature. Before the annexation, the Kerch Strait was considered a shared water area of both Russia and Ukraine, and projects like this one would have proceeded upon agreement between the two parties. Currently, there is no such agreement, and, according to some Ukrainian legal experts, Ukraine may well put a stop to the project, using this legal gray area to its advantage. Even a Russian official, Crimea's governor Sergei Aksyonov, mentioned that possibility in 2015.

In March 2016, the Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that "all the aspects of international law have been taken into account" when deciding upon the fate of the project. Judging by the fact that construction is well underway, the Kremlin doesn't appear too worried.

Construction on the bridge is well under way but the ambitious completion date — December 2018 — is fast approaching. There will be 7,000 piles driven into the bottom of the Kerch Strait.

Marking Territory

The question about whether it is worth going to so much trouble remains unanswered.

Authorities could have chosen a cheaper and easier solution, says Mikhail Blinkin, transportation and road construction expert.

For Blinkin, the most obvious answer is a better ferry connection. "They could have bought more ferries and docks abroad, brought them to the strait, and the transportation problem would have been solved for the next 100 years," he told The Moscow Times.

Crimea, with its moderate passenger and cargo traffic, doesn't really need a bridge that big, he says. "If there was some sort of extracting industry in the region, and there was a need to transport, say, coal — then a bridge would be crucial," he says. "Crimea is a tourism region and this project is purely political — it aims to mark the territory."

Given the politics at stake, it is highly unlikely the project will fail. "It is very complicated from a technological point of view, but they've done thorough research, and only a major force can make it fail," says Zege.

Contractors that work on the Kerch bridge might even meet their December 2018 deadline, provided they receive regular funding in time. Pauses in funding will inevitably stall construction.

This should not be viewed as such a big deal, says Schulmann: "It's not the Olympics, or some other event people will be attending. With the bridge, they can delay it all they want."

Contact the author at [email protected]. Follow the author on Twitter at @dashalitvinovv

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.