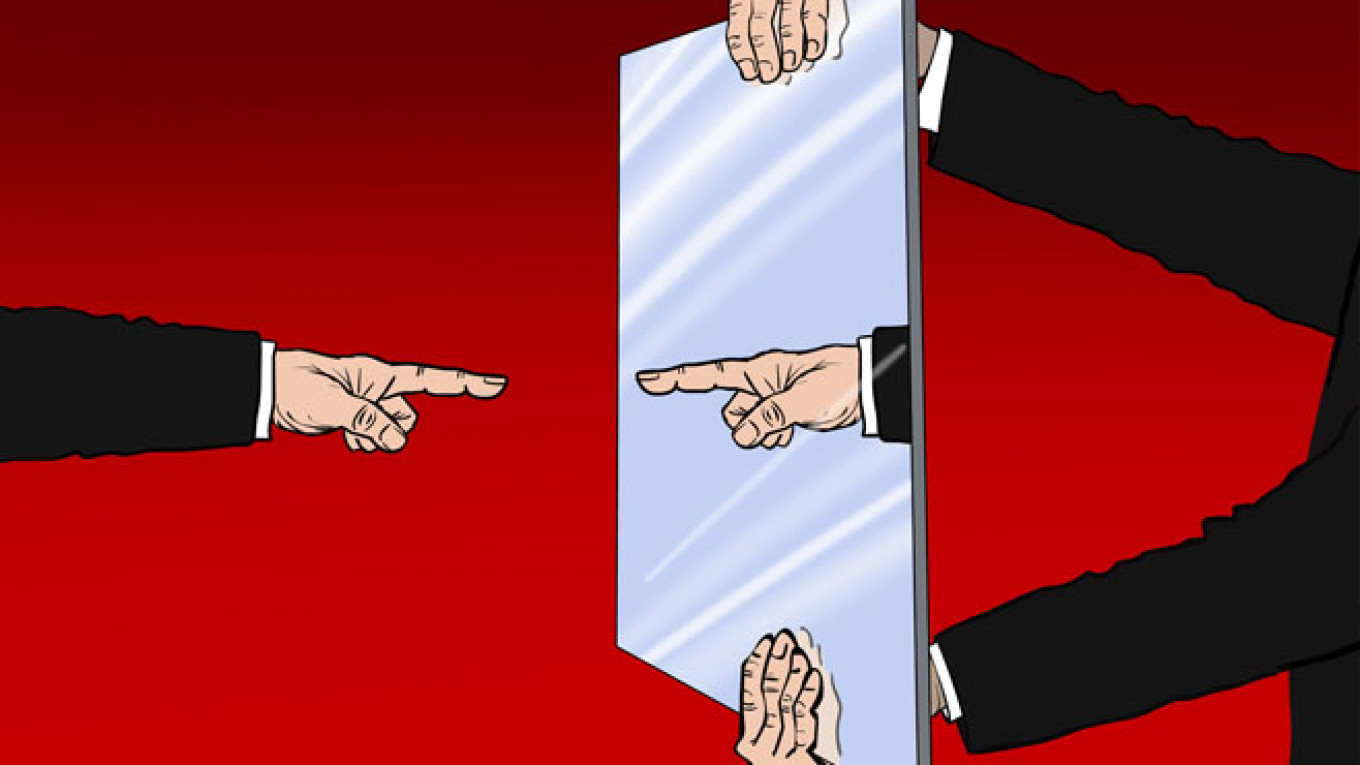

There are few things in the world that drive Russia hawks battier than "whataboutism," a Soviet-style debating tactic in which any criticism of Moscow's policy would immediately be met with "but what about … " and then a long litany of Western sins such as racism, colonialism, militarism or economic exploitation.

Whataboutism was employed by the Communist Party with such frequency and shamelessness that a sort of pseudo mythology grew up around it. Any student of Soviet history will recognize parts of the whataboutist cannon.

Whataboutism's efficacy decreased for a certain period of time, in no small part because many of the richest targets (like the Jim Crow racial segregation laws) were reformed out of existence, but it has made something of a rebound over the past few years.

Because of its nature there has never been, and never will be, any real agreement on exactly what constitutes whataboutism. One person's helpful historical and political context ("After Kosovo, who are you to criticize us for changing borders?") becomes someone else's irrelevant distraction ("Ferguson means you can't lecture us about anything.")

At its best, whataboutism can help illuminate interesting commonalities between different countries that, at first glance, have nothing in common. At its worst, which unfortunately is a lot more common, whataboutism degenerates into crude, useless and intellectually harmful propaganda.

At its heart though, whataboutism is a logical fallacy. Essentially, it amounts to responding to a specific criticism with "look over there, a squirrel!" As such, it deserved to be criticized and, on occasion, combatted. It's certainly not something that should be celebrated.

Westerners justifiably criticize Russian official media outlets for going overboard on whataboutism, for answering any and all potential criticisms of Russia with counterexamples of American perfidy.

It has gotten to the point where even completely objective data-based observations (e.g. "Russia's economy is shrinking") are immediately met with shrill cries ("But what about the U.S. government's budget deficit?").

However, while they are generally justified, there is an awful lot of self-satisfaction in criticisms of whataboutism, as if it was somehow distinctively or uniquely Russian. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

The roots of whataboutism won't be found in the Kremlin or the hallways of RT, but, to slightly modify a famous quote from Alexander Solzhenitsyn, in every human heart. People don't like to confront their own misdeeds and generally find it far more convenient to focus on someone else's errors and mishaps. It's just a basic part of human nature.

All of which brings us to an enlightening example from the United States. Tom Cotton, a recently elected, and supremely hawkish, Republican senator from Arkansas was asked to weigh in on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, a controversial Indiana state law that would allow businesses to cite their personal religious beliefs in any lawsuits arising over alleged discrimination.

While the bill doesn't explicitly target gays and lesbians, criticism of it has centered on the idea that it would allow businesses to systematically deny services to same-sex couples (for example, a restaurant that refused to cater a gay wedding).

For a whole host of reasons, this law has caused a wall-to-wall media firestorm here in the United States. For about a week it nearly monopolized the political conversation. Actors, athletes, musicians — almost everyone weighed in with their personal "take."

Cotton's response was a dictionary definition of whataboutism. A trained lawyer, he made little attempt to affirmatively defend the law on its own merits. He didn't argue that there was any pressing need for such a law, nor did he say that the law would do anything to make Indiana's citizens better off than they were before it was passed.

Instead he made the following statement: "It's important that we have a sense of perspective about our priorities. In Iran they hang you for the crime of being gay."

Cotton is famous for wanting to inject "morality" into foreign policy, arguing that the United States has a duty to spread democracy around the world and to support like-minded regimes against any and all challengers.

It's thus particularly ironic that he indulged in a rhetorical practice that his own ideological allies have frequently criticized for being "relativist" and amoral.

Cotton's attempted dodge was so crude and unconvincing that he caught a lot of flak for it. But it is a very helpful and clear reminder that we don't need to go very far in search of whataboutism: It's not a logical fallacy that lives only amid scary foreigners and "propagandists," but among all of us.

So, by all means, criticize the Russians when they try to change the subject. But as you search for the sawdust in your neighbor's eye don't lose track of the plank in your own.

Mark Adomanis is an MA/MBA candidate at the University of Pennsylvania's Lauder Institute.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.