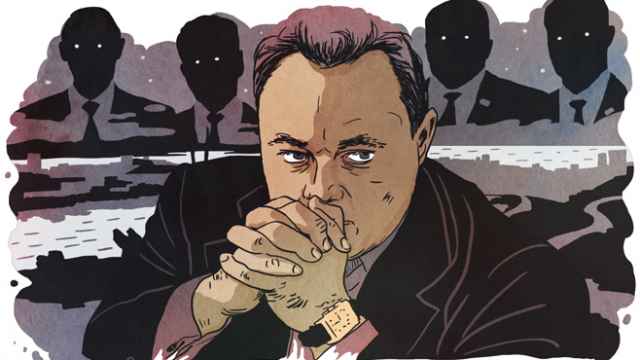

This week, Evgeny Urlashov, the former mayor of Yaroslavl, sits in prison and awaits his sentence. An anticorruption activist, Urlashov was arrested in 2013 on bribery charges. He was a popular figure in the city of 600,000 people, winning a landslide victory against a Kremlin candidate in elections a year earlier.

Authorities are accused of leading a political trial against Urlashov: he was, after all, getting too popular, and at a time when the Kremlin was fighting the biggest street protests in its post-Soviet history. The story of his success and downfall casts a spotlight on an ever more vulnerable job in Putin's Russia: being mayor in a regional city.

In Putin's third term, the Kremlin has been unceremoniously putting city mayors behind bars. From Yaroslavl to Makhachkala to Vladivostok, city authorities are feeling the heat. Since Putin came back to the Kremlin in 2012, Russia has arrested, detained or interrogated the mayors of more than 25 cities. Only a tiny minority of them were from opposition parties, and most were charged with bribery cases.

Barely a few weeks go by without Moscow parading the arrest of yet another mayor. The last well-known victim of the purge was Vladivostok mayor Igor Pushkarev. On the night of the 1st of June, FSB arrested Pushkarev and brought him to Moscow, raiding his office and family home in the process. Pushkarev stands accused of selling state contracts to businesses owned by his relatives.

“It's much easier to catch mayors taking bribes,” says political analyst Evgeny Minchenko. Mayors are responsible for municipal budgets, which are often severely under-funded and thus more susceptible to corruption.

Governors, on the other hand, have more protection more Moscow and less visible contacts with budgets. They are assumed to be political figures, and going after a governor requires Moscow's permission. Firing and arresting mayors is also one way for governors to show they are doing their job.

At the same time, Russia's opposition has been able to have some considerable successes in mayoral offices. Anti-corruption campaigner Yevgeny Roizman has managed to hold on to his position as mayor of Yekaterinburg. Until last year, Karelia's Petrozavodsk was home to female opposition mayor Galina Shirshina. And, famously, Urlashov was mayor of Yaroslavl, however briefly.

“It was the only political position left for the opposition,” says Aleksandr Kynev, a political scientist at Moscow's Higher School of Economics. In 2005, Russia scrapped regional elections of governors, meaning the Kremlin could appoint anyone it wants instead. City mayors were the one electable position, and candidates like Roizman were able to run successful, largely non-political campaigns — in Roizman's case on an anti-drug platform.

The mayoral purge is not exclusively centered on the opposition, however. Even loyal candidates have been targeted. In 2012, the Putin loyalist mayor of Astrakhan Mikhail Stolyarov stood accused of election fraud. His rival, Just Russia candidate Oleg Shein, claimed he won the election and went on hunger strike. The fight for re-election lasted for a few months, even luring opposition leader Aleksey Navalny from Moscow to Astrakhan. Eventually, the opposition lost and Shein ended his hunger strike and Stolyarov became mayor of one of Russia's biggest cities. The following year, however, Stolyarov was arrested and charged with accepting a bribe of 10 million rubles.

With September's parliamentary elections around the corner, the purge of regional mayors is, if anything, likely to intensify. For Russian officials, the message is clear: one step out of line, and corruption charges could be just around the corner.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.