I found my customer, Misha — a mountain of a Siberian man — standing in the tail section of the plane. It was 1994 and we had just completed a successful “reference visit” to one of Hewlett-Packard’s oil industry customers in Canada. Misha was grasping a bag with dozens of mini-bottles of alcohol he had obtained from the stewardess. Now he was trying to secure a volume discount.

“Misha, we’ll be in New York in three hours,” I told him. “I’ve got a barbecue planned at my parents’ house. There will be plenty of beer and vodka.”

“Beer? Vodka?” he repeated. I nodded. “But, only in three hours?” he asked. I nodded again. He completed the transaction and consumed his booty before we landed.

Alcohol was a significant element of doing business in Russia in the early 1990s. Many features of the Russian commercial landscape have changed or disappeared since then. Some are missed: well-paid expat positions, limited government reach, the ability to get to across town within 30 minutes for a meeting, and even the need for face-to-face meetings.

Good riddance to others: the dilapidated telecoms infrastructure, mounds of paperwork on actual paper, mythological customer budgets and the need to have a krisha (a “roof”) to protect your business from banditry.

We’ll all live longer without so much booze, but it accompanied adventures and relationships I cherish. Each industry had its preferred spirit. The oilmen loved their vodka. A midwinter business trip to Noyabrsk — where at minus 35 degrees Celsius hair freezes and cracks and spit solidifies before it hits the ground — would convince even a teetotaler to use personal antifreeze. Telecoms executives mostly drank whiskey. Grain alcohol was available at their office parties — they used it to clean mechanical switches. Aerospace industry people liked cognac. I shared a bottle of 15-year-old Ararat with the IT manager of the Mission Control Center in Korolyov. We had just watched the fiery demise of the MIR space station, which had been orbiting the Earth for 15 years. Bankers? Well, they seemed to drink anything.

The Arc of Adventure

It wasn’t just about alcohol. When the 1990s got wild, the representation office was the standard organizational format for foreign companies. A position in such a firm gave Russian professionals benefits formerly only available to upper echelons of the Party elite: a few hundred dollars in hard currency monthly, a clothing allowance, a company car and business trips abroad.

“It was like a dream,” said one Russian businessman who has partnered with foreign firms for more than two decades. “Dealing with foreigners was very interesting. We all wanted some connection to the outside world.”

Some dreams turned into nightmares. “Some came with their 5, 10, or even 100 thousand dollars, lost it all, and left,” said a Russian entrepreneur. “Why did they lose it? Because it was a swamp here. No rules, no law enforcement. If your partner suddenly took a disliking to you, you were gone.”

Some foreign entrepreneurs mastered the relationship factor, like Peter Gerwe, who arrived from California and started a media empire, or Bernie Sucher, who turned his hankering for Americanstyle food into the Starlite Diner. Courage, a nascent regulatory system and excessive enthusiasm all facilitated success.

Along the way, Russia got a large dose of the West. Foreigners brought their arsenal of tools and treats: business processes, philanthropy, transparency, corporate culture, and — when margins were fatter — extravagant corporate spending on events and gifts.

“We exposed our business partners and government interlocutors to all these lavish things and they began to adopt them,” said the head of an American multinational who has been in Russia since 1992. “Then, in Russian fashion, they went to extremes and continued these traditions long after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act inhibited us.”

The infection went both ways. Western firms Russified. A generation of young Russians gained experience and now run most of those companies. The standard of living increased, people traveled abroad and the euphoria for all things foreign subsided. Business became routine.

That dynamic, combined with the current geopolitical situation, has led to an about-face in mindset. CoCom export controls and the Cold War have been replaced by sanctions, anti-sanctions and import substitution.

“In the 1990s, we were like a river of water seeking its path, picking up sediment from wherever, going with the flow, open...,” the entrepreneur said. “Now, it’s as if our state of matter has changed: We are ice. We say if you want to be friends with us, it’s up to you to try harder, make the best offer, consider our needs.”

Bureaucratic Evolution

Meanwhile, bureaucrats have multiplied and gained competence. However, big and small businesses have different views on the state of corruption.

“It’s out of control,” said the Russian entrepreneur. “There are more inspections and certifications. People used to say: ‘We’ll create something and then get rich!’ Now, there’s little enthusiasm. We only have the appearance of change. Instead of bandits there are lawyers.”

But the head of the American multinational feels more secure. “The ’90s were scary,” he said. “You had to have a krisha — or borrow your partner’s — to defend yourself from racketeers... Now, with the state in control, things seem much safer.”

“The bureaucrats are less corrupt, in part, because you hardly meet them anymore — obligatory reporting to ministries is mostly done online now,” the American businessman added. “On the rare occasion that I do go to them, they are often smiling, chatty...maybe they miss the human interaction, too?”

It Was Personal

In the ’90s, you got customers through your relationship with the decision maker.

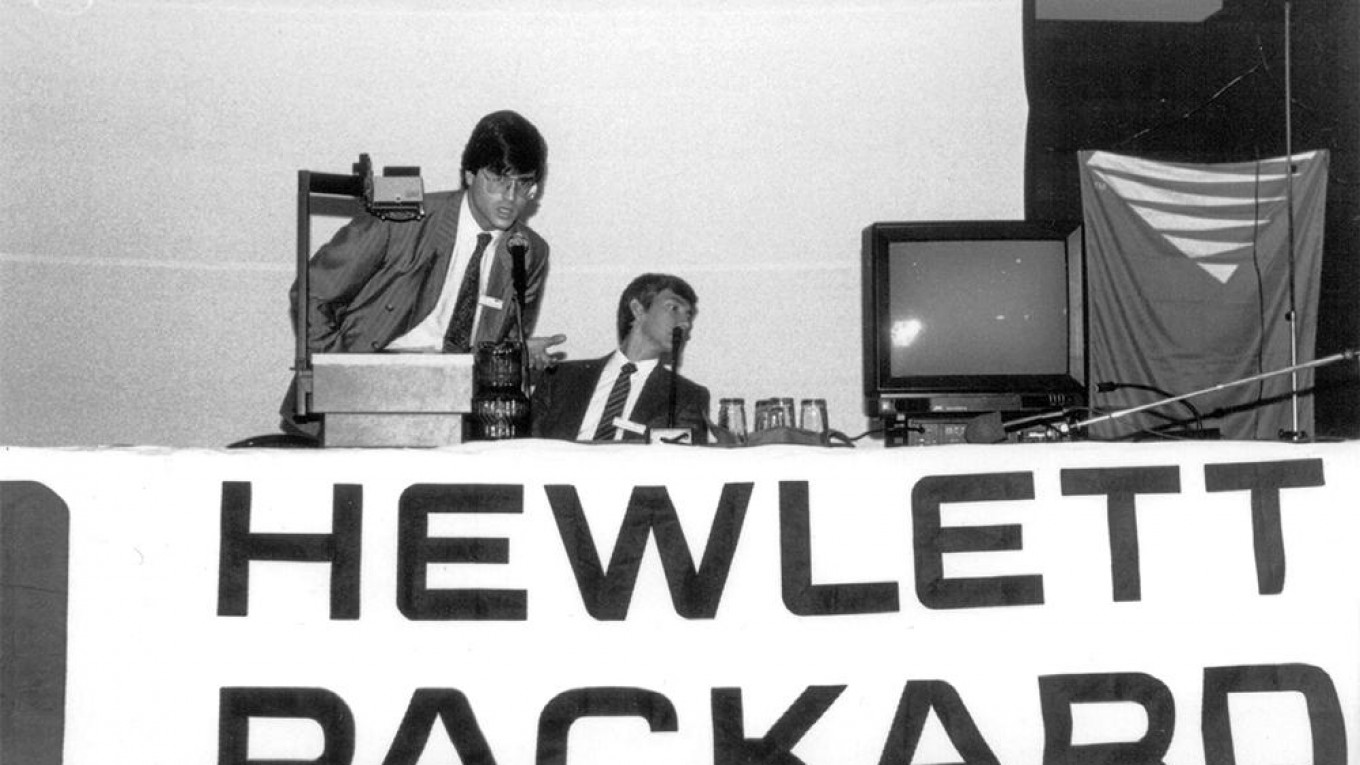

In 1996, Pepsi paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to have cosmonauts aboard the space station display a giant soda can. About the same time, my colleagues and I at HP gave the Russian Mission Control Center a few amortized demo computers. In exchange, we were allowed to place our logo banner under the center’s main control screen for many years.

I got good advice early on. The deputy general director at a state company told me: “If you come to a meeting with a pen and note pad listing your agenda, you’re not likely to get what you want. If you come with some jokes, describe your philosophy of life, and tell stories about your family — saving the business for the end — you are bound to get what you need.”

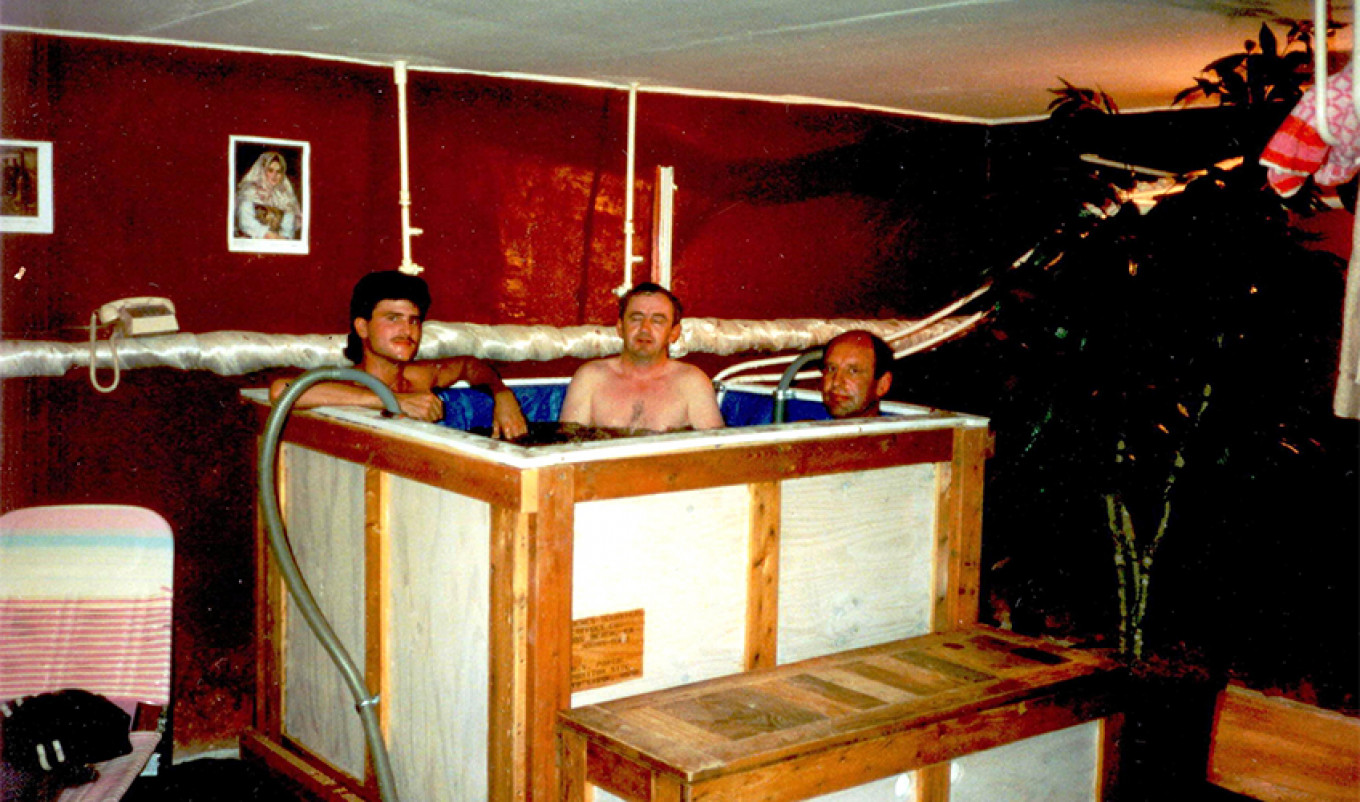

The banya epitomized customer intimacy. Sitting in a room naked and sweating together, you were bound to bond — even if your note pad got soggy.

Russia will always be a peculiar market. The high-profit margins most foreign companies enjoy here ease the challenge of explaining “Russian reality” to headquarters. But the camaraderie of the banya is something that can’t be explained. It has to be experienced.

Justin Lifflander is a former business editor at The Moscow Times and author of the book “How not to Become a Spy.”

*This article is part of The Moscow Times' 25th anniversary special print edition. To view the entire issue click here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.