"What is the Thaw? People often can’t explain what it is. Everyone says there was a special atmosphere in the air, a kind of sincerity, a distinct spirit...”

As Anastasia Kurlyandtseva, one of the curators of the “Thaw” exhibition at the New Tretyakov Gallery points out, the era, which began as Khrushchev took over from Stalin in the mid-1950s, continues to defy classification even now. The flirtation with a more open form of socialism ended with Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968, ushering in a new age of censorship and tight state control.

The exhibit is part of a kaleidoscopic triple project under the title “The Thaw: Facing the Future,” which sees the Tretyakov, the Museum of Moscow, and (later in March) the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts joining forces to explore the historical, social and cultural significance of the period.

The two current exhibitions aim to address the lasting ambiguity surrounding the Thaw (“Ottepel” in Russian) by providing an overview of the transformations that took place in Soviet society after Stalin’s death, when the paranoid state structures of the USSR began to loosen, resulting in a genuine cultural shift.

A question of perspective

For decades, historians have defined the Thaw largely through isolated events: the stunning victory by American pianist Van Cliburn at the inaugural International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in 1958, the American National Exhibition at Sokolniki Park in 1959, and the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” in 1962, among others.

Yet, the Thaw continues to provide more questions than answers: Was it a state-orchestrated change of direction aimed at harnessing the pent-up creative energies of a frustrated society? Or was it a gradual collective awakening, an organic social impulse?

One of the enduring problems with defining the Thaw, says Kurlyandtseva, is that the average Russian visitor “knows what the British 1960s are about —the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Twiggy. But concerning what happened during the Soviet 60s, there’s a very fragmented global picture, which doesn’t put the pieces of the puzzle together.”

Whereas previous attempts to understand the period have focused on its visual art or its literature, the curators of the respective “Thaw” exhibitions realized that a more holistic approach was required — one that didn’t neglect the developments in the sciences and the social sphere that accompanied the artistic and literary milestones of the Thaw.

“This is an exhibition about the Thaw as

a project,” says Yevgenia Kikodze, curator of

the ‘Moscow Thaw’ exhibit across the river

at the Museum of Moscow, which has been

open since December. Kikodze sees the period

as an opportunity for Soviet society that

was only partially taken: “What is the Thaw

but a kind of chance?”

“It was an attempt to [explore] a historical turning point, when it was possible to follow either one road or another, and we wanted to return to that place where that fork in the road did not yet exist,” she says.

Differing approaches

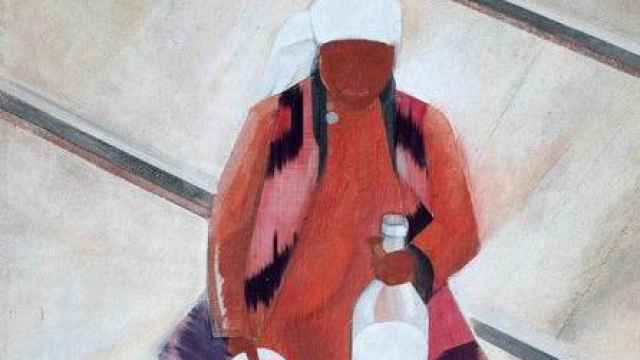

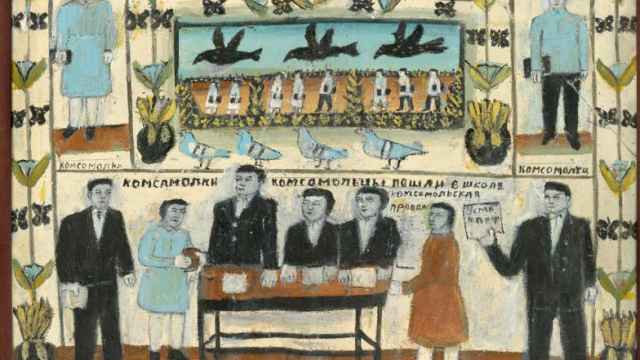

While naturally there is substantial overlap between the two exhibitions, with works by artists of the time such as Yury Pimenov and Mikhail Roginsky displayed in both shows, the museums attempt to reach an understanding of the period in different ways. At the Tretyakov, the exhibition is divided into seven distinct thematic sections with names like “A Conversation with Father,” “The Best City on Earth,” and “International Relations,” grouped around a circular central area that represents Moscow’s Ploshchad Mayakovskogo (now Triumphalnaya).

“This is one of the cult places where various events took place… it’s a place where people could socialize in those years, where they came to listen to poets give readings, where they came to talk,” says Kurlyandtseva.

In fact, the whole exhibition takes the form of a “city,” with the display boards built to resemble the prefabricated panel housing that sprang up in the suburbs as a response to the housing crisis of the post-war years.

“A Conversation with Father” ushers visitors into the space, establishing a stark but vital counterpoint to the optimism of the rest of the exhibition: the revelations about the abuses of the Stalinist period and the Gulag that began to emerge in the mid- 1950s.

The other sections feature sculptures, paintings, photographs and fragments of films made during the period, along with household items such as dinner services, vacuum cleaners, radio sets, the designs for many of which were clearly inspired by the country’s achievements in space.

There is an almost festive atmosphere on show here, from the documentary footage of the Moscow International Festival of Youth and Students in 1957, to the celebrations of Soviet achievements in space and the tachist canvases of Anatoly Zverev, inspired by Jackson Pollock.

But where the Tretyakov show arranges its exhibits into clearly defined cultural categories around a central forum, the Museum of Moscow delves deeper, asking the viewer to analyze the period through a more abstract prism.

As Kikodze explains, the overarching theme is that of the “matrix,” representing the era’s universality, interconnectedness and lack of dominant cultural figures. Here the exhibits—a vast range of artworks, household items and other paraphernalia—are split into nine zones under symbolic concepts such as “Matrix,” “Capsule,” “Rhythm,” “Transparency,” and “Absence.”

Often similar material appears in sections that appear to be mutually incompatible, but which reflect the contradictions of the era. For example, designs for the planned city of Kritovo (never built) are categorized under both “transparency”—focusing on the open-plan aspects of new mass housing—and “capsule,” symbolized by the new “micro-districts” of apartment blocks, and the retreat of society into the interior worlds of individual experience.

Misspent optimism?

For both Kurlyandtsevaa and Kikodze, the Thaw should be seen in an optimistic light: “It gives us ground under our feet, tells us that it’s possible, but that certain things need to be done...” says Kikodze, arguing that it is vital that Russian society understands that things don’t happen by themselves. “We had a chance to realize this project, and it didn’t work out, but we still have that chance,” she says.

Yet amid all the optimism on show, there is a lingering feeling that perhaps both retrospectives take a view of the period that is too rose-tinted, that they ultimately avoid uncomfortable questions that are particularly resonant today. Was Soviet society complicit in the end of the Thaw by an unwillingness to risk the gains it had made? Would another society have acted more boldly in defense of its values?

A disturbing parallel with the present can also be drawn. After all, the Thaw was not the last time that a period of relative openness in the country came to an end with Moscow’s military intervention in a neighboring state that the Kremlin feared was slipping away from its orbit.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.