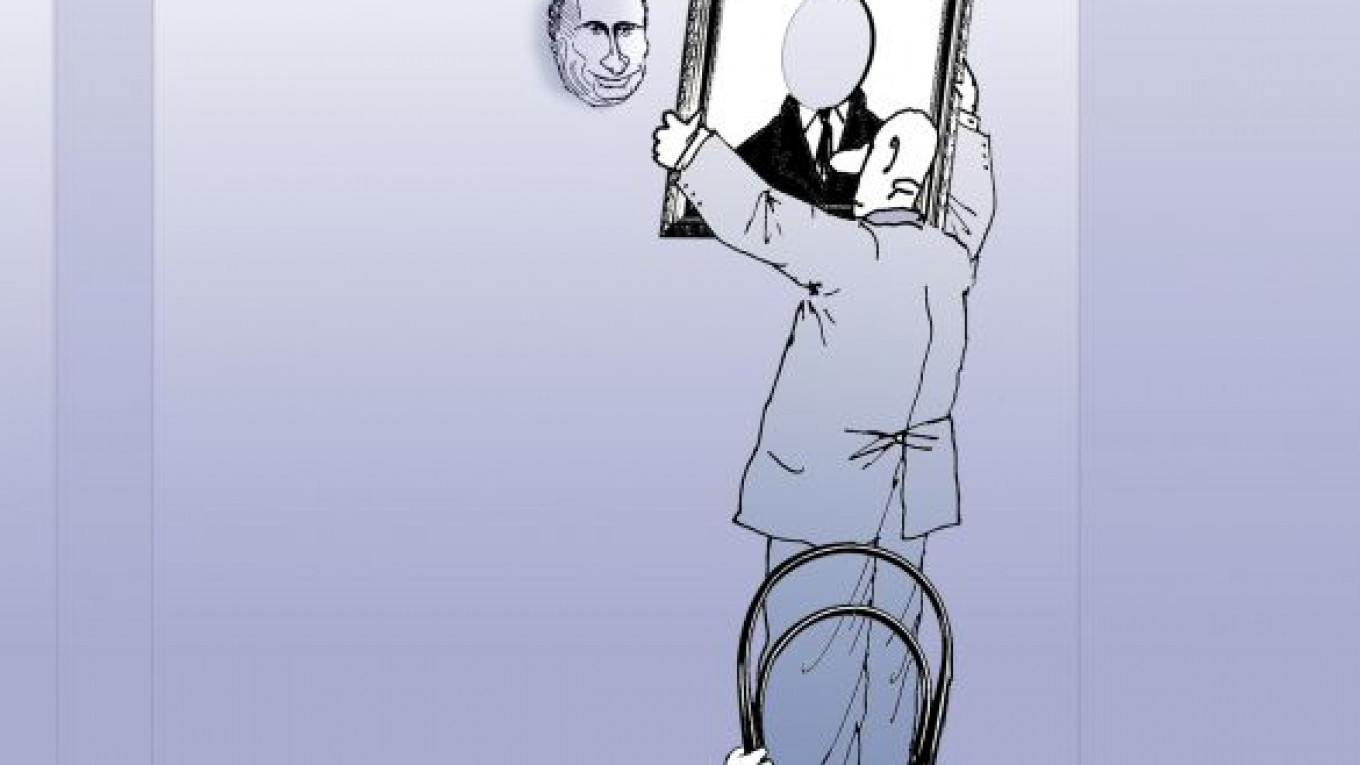

When it comes to Russian politics, the Wizard of Oz may have been right: pay no attention to the man (or, in this case, men) behind the curtain. Please.

Run through recent headlines in the Western press on Russia, and you'll find a lot of attention paid to the power struggles that have gripped Moscow in the past few months. Headlines in the Russian press aren't much different. Corruption-related scandals have brought down lawmakers, Olympic bureaucrats and, most notably, former Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov. Accusations of incompetence and even treason — presented in slickly produced YouTube videos — have even sought to undermine Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev.

All of this has led to a rash of speculation as to who is going to be Russia's next president. Serdyukov and Medvedev, evidently, are out. Perhaps Sergei Shoigu, a Putin loyalist and Serdyukov's steely replacement in the Defense Ministry? Or nationalist firebrand and former ambassador to NATO Dmitry Rogozin, whose machinations on behalf of the military industrial complex are widely believed to have led to Serdyukov's downfall?

It doesn't matter, and not only because Vladimir Putin is less than a year into a six-year term, after which, if he wants it, he can more than likely have another. It doesn't matter, because it's entirely beside the point. And that's the point.

Russia faces very real policy problems. Leaving aside short-term tasks, such as having to pull off the Olympics in only a year's time, at a total reported cost of $50 billion and growing, the Kremlin faces a spate of seemingly intractable mid- and long-run challenges. The budget remains mired in deficit, despite high oil prices and a relatively benevolent global economy, a situation that will only be exacerbated by increasing social obligations and decreasing economic productivity.

Regional budgets are in even worse shape. Rising birth rates are a good sign, but they won't be enough to overcome an already built-in demographic slump, which could deprive the country of as much as 15 percent of its workforce over the next 20 years. Threats to security, already felt in the Northern Caucasus and along the border with Central Asia, will multiply when the U.S. pulls out of Afghanistan next year.

The list could go on, but it doesn't have to. Russia has the answers to many, if not all, of these questions. Radical efforts are under way to breathe new life into higher education, integrating it with global academic communities, led by a fresh crop of public officials and university leaders. Twin initiatives — including the government's attempt to bring money back into the country from off-shore accounts and the Central Bank's drive to switch from exchange-rate to inflation-targeting — will increase economic efficiency and make the economy more transparent and less volatile, a boon to investors both domestic and foreign. The road ahead will be difficult, but it is passable.

No one is well served, however, by this political masquerade. No one, that is, except those who would like to see Russia continue doing business as usual, rife with inefficiencies and the opportunities for corruption they create.

When Putin first became president in 2000, most Russia watchers — including most Russian citizens — spent his first term trying to discern what sort of president he would be. They spent his second term wondering whether he would try to engineer a third. When he didn't, and Medvedev took his place in 2008, we spent four years wondering whether Putin would come back.

Now that he is back — and, just as he never really left in 2008, we would do well to assume that he has no plans to depart the political scene any time in the next 11 years — those of us who want to see Russia and Russians make progress need to turn our attentions elsewhere. Rather, the focus should be on policy, on developing and critiquing ideas that address the problems Russia faces. Not only do the internecine battles in and around the Kremlin distract us from what matters, they're specifically designed to distract us from what matters.

We can talk about the difficulties of bringing Russia's rusting armed forces into the 21st century, and perhaps helping to integrate Russian foreign policy into global crisis resolution mechanisms along the way, or we can guess at which general is closest to power. Likewise, we can seek to understand the causes and preventions of corruption, or we can try to parse out the political ramifications of the most recent arrest for competing clans with an eye to 2018. We can look at what Putin, his friends and his enemies are doing behind the curtain, or we can deal honestly with the complexities of everyday Russian life that are right out in the open. But we cannot do both.

Sam Greene is senior lecturer in Russian politics and director of the King's Russia Institute at King's College London.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.