In the space of a month, Russia was shocked by several violent suicides involving terminally ill patients.

In a small town in Siberia, an elderly man placed an explosive device in his mouth and detonated it. In a Moscow region town, a man died after blowing himself up with a homemade bomb. In the southern Krasnodar region, a man was reported to have shot himself with a homemade gun. Another man was found dead in his Moscow apartment: Police concluded he had also committed suicide. All were reported to have struggled with cancer.

According to rules imposed by state media watchdog Roskomnadzor in the spring of 2015, Russian media outlets are not allowed to mention the reason for a suicide in their reporting. Whatever the reason in these particular cases, however, it is reasonable to assume the intense pain, bureaucratic hassles and scrutiny connected with painkiller prescription in Russia were contributing factors.

An Ordeal

A standard procedure in the West, the process of obtaining painkillers for relatives diagnosed with incurable diseases is rarely straightforward in Russia.

For months 40-year-old Varvara — not her real name — shuttled from one edge of Moscow to the other. From her bedridden mother, she would travel to an oncologist on the opposite side of town, who would decide which painkiller to prescribe. She would spend hours waiting in line at her local physician, who would issue an actual prescription. Then, she would have to travel to a specialized pharmacy, where she would often find out that the prescription was filled out incorrectly, and rush back to start the process all over again.

It would sometimes take Varvara several days to lay hands on the pills — several days during which her mother suffered from severe pain.

Varvara was made to feel like a criminal. Nurses from the local clinic would show up unannounced at her home, demanding she turn over empty packages and checking how many pills her mother had taken. The oncologist initially refused to prescribe morphine, arguing it was “addictive” — as if this was a significant issue for a 70-year-old woman with only months to live. The local clinic refused to issue a death certificate until Varvara returned all the unused morphine.

“Thank God my mother had me to help out,” says Varvara. “I have no idea how those who live alone could cope.”

Irina Apanasenko, the wife of retired Admiral Vyacheslav Apanasenko, who struggled with cancer for years, told reporters a similar story after her husband killed himself in February 2014.

On that tragic day, Irina spent an entire afternoon in the local clinic, trying to fill a prescription for morphine. At first, her physician refused to comply with the oncologist’s recommendation, citing incorrect dosage. Only after 40 minutes of consultations and running back and forth from one doctor to another, Apanasenko was given another prescription — with the same dose. All that remained to do was have the deputy chief doctor sign it. Unfortunately, the official had left work five minutes earlier than usual that day. So Irina, stressed and exhausted, returned home without the medication.

The next morning she found her husband in bed with a fatal gunshot wound. “I am prepared to suffer,” the note he had left on the table read. “But to see the suffering of those close to me is an unbearable pain.”

Apanasenko’s suicide made headlines and brought the issue of pain relief back into the spotlight. It soon turned out he was not the only one ready to take his own life because of the pain. Reports of other cancer patients committing suicide started to surface.

The Russian authorities reacted in a typical manner — censorship. In March 2015, Roskomnadzor prohibited media from reporting why people commit suicide. But it was too late: Many gruesome tales were already out there.

Some Progress

On the back of several high-profile suicides in 2014 and 2015, and under pressure from NGOs and public outrage, the Russian government was moved to make concessions. In June 2015, pain-relief prescriptions became valid for 15 days instead of just five, the number of pharmacies allowed to distribute narcotic painkillers increased, and a 24/7 hotline opened for patients experiencing difficulty getting pain medications.

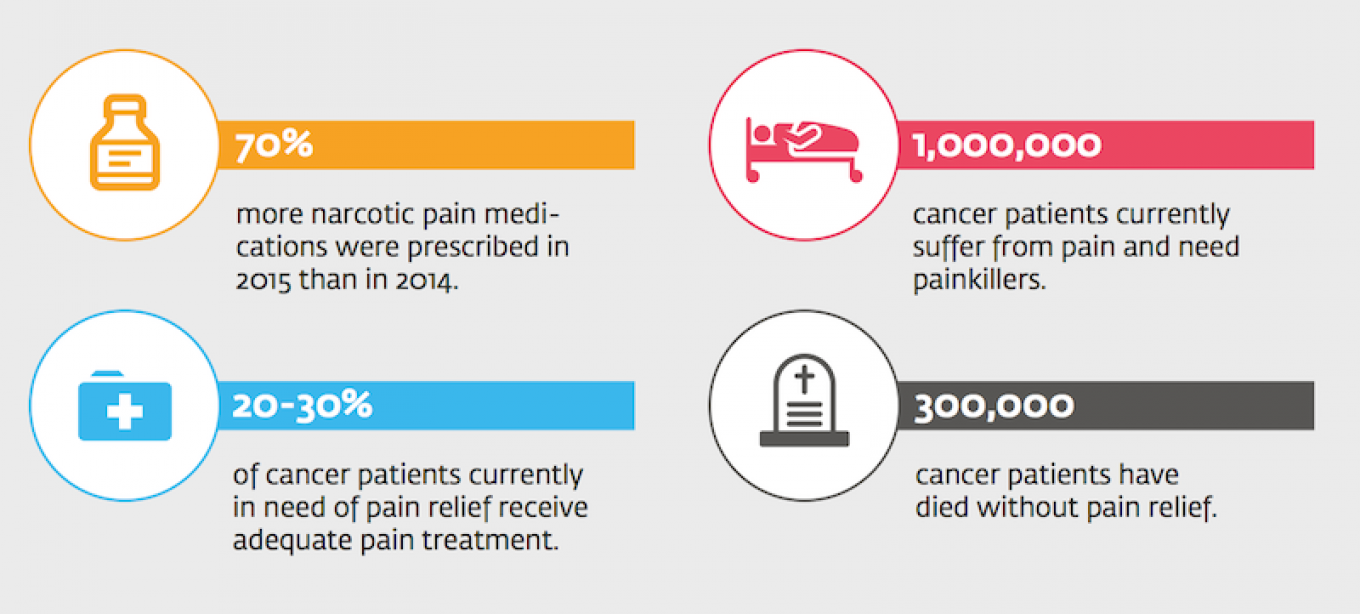

The new regulations had an obvious effect. Seventy percent more narcotic pain medications were prescribed in 2015 than in 2014. NGOs and hospice workers saw the waiting time for a child with terminal cancer to receive painkillers reduced from two weeks to 24 hours.

“It’s huge progress,” says Yekaterina Chistyakova, director of Podari Zhizn, a foundation that helps cancer patients get pain medications. “But it isn’t enough: Currently, only 20-30 percent of cancer patients receive the painkillers they need.”

The seat of the trouble continues to be the mind-set of Russian doctors, who tend to ignore quality of life issues. It is a mentality that most probably derives from Soviet times, says Lida Moniava, head of the Children’s Hospice in Moscow. “Doctors were not taught to evaluate the level of pain and to plan treatment accordingly,” she says.

Many of them don’t see pain as the problem in need of treatment. Patients are told that pain is to be expected and endured when diagnosed with such serious illnesses. As a result, Russian doctors today rarely know which pain medications to use, what treatment schemes to recommend, especially when it comes to new developments in the field.

“The key to increasing access to pain relief is to improve the qualification of doctors,” says Chistyakova.

In addition, doctors still fear criminal prosecution. You don’t need to sell morphine to a drug addict to be charged for criminal behavior. Incorrectly destroying or storing an empty vial is often enough for criminal prosecution. Doctors are spooked by the example of Alevtina Khorinyak, a physician from the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk, who prescribed an opioid painkiller to a man who wasn’t technically her patient and wound up standing trial for the illegal distribution of narcotics.

“Many remember that there was a criminal case. But few realize that Khorinyak was exonerated in the end,” says Chistyakova.

The Russian government insists it is listening, and the most recent developments seem encouraging. In July 2016, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev signed into action a new roadmap aimed at increasing painkiller accessibility. The document proposes expanding the range of available pain relief medications, introducing modern schemes of treating pain and delivering palliative care, simplifying prescription and decriminalizing minor rule-breaking. The document was put together by government officials and experts from specialized NGOs, and some see in it grounds for a major breakthrough.

The devil, cautions Chistyakova, is in the implementation. “The state needs to deliver the road map in full and not pro forma, which is very difficult,” she says.

Global Perspective

Russia’s problems are hardly unique. The demand for adequate pain relief is balanced against potential narcotic misuse across the globe, says Dr. Nicola Magrini, a medicines expert at the World Health Organization.

“Every time [the authorities] try to regulate it better, they decrease access, and every time they expand access, they increase misuse,” says Magrini. “It is a very complicated problem.”

According to the WHO’s recommended scheme, pain relief should be administered to cancer patients in three stages. The first stage is over-the-counter, non-opioid pain medications such as aspirin or paracetamol. When the pain persists or increases, a patient should be administered mild opioids, codeine, for example. When mild opioids are not enough, strong opioids such as morphine should be prescribed.

But, as Magrini explains, the scheme only works in conjunction with proper medical oversight. Doctors should manage side effects (significant when it comes to morphine) and adjust the dosage to counteract tolerance. “It doesn’t work if patients are abandoned and only seen by doctors once a month,” Magrini says. “They should be monitored at least twice a week, or contacted on a daily basis to see how they are doing.”

In Russia, monitoring continues to be less focused on the patient than on the drugs being prescribed.

As Vavara recalls, the nurses that came to visit never bothered to ask how her dying mother was doing: “Instead, they lectured me on administering too many pills — but what exactly is too many for someone who is screaming from pain at the top of their lungs?”

According to data presented in the government road map, there are currently 1 million cancer patients in Russia in need of painkillers. Another 300,000 Russian cancer patients died without pain relief.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.