How do you surprise a festival whose raison d’être is shock and awe and whose winners include a bearded drag queen in a gold-sequined dress?

Perhaps, as Russia did this week, by nominating a singer in a wheelchair. Ever since state television’s Channel One announced it had selected Yulia Samoylova as Russia's entry for the song festival last week, Eurovision has dominated conversations in the media and online.

Few expect Samoylova’s love ballad “Flame Is Burning” to be a winning song. But that, some commentators have remarked, is a secondary concern. They say Russia is not in it for the Eurovision points — it is in it to claim the moral high ground.

A festival that is as much about geopolitical favoritism as it is about kitschy camp glam, Russia's participation in the song festival has long been a topic of controversy.

In 2014, the year Russia annexed Crimea and conflict flared with Ukraine, its act got booed. Last year, it lost the title to Ukraine, coming third. The defeat was all the more humiliating because the winning artist was a Crimean Tatar who sang about the repression of her people under Stalin — an unmistakable nod to the ethnic minority's current troubles under Kremlin rule.

So with Kiev as this year's host, Russia's choice of candidate was always going to be interpreted as a political message. Not that Moscow would acknowledge this so openly.

“Yulia is a unique singer, an enchanting girl and an experienced contestant,” the head of Russia's Eurovision delegation Yury Aksyuta was cited as saying by the channel.

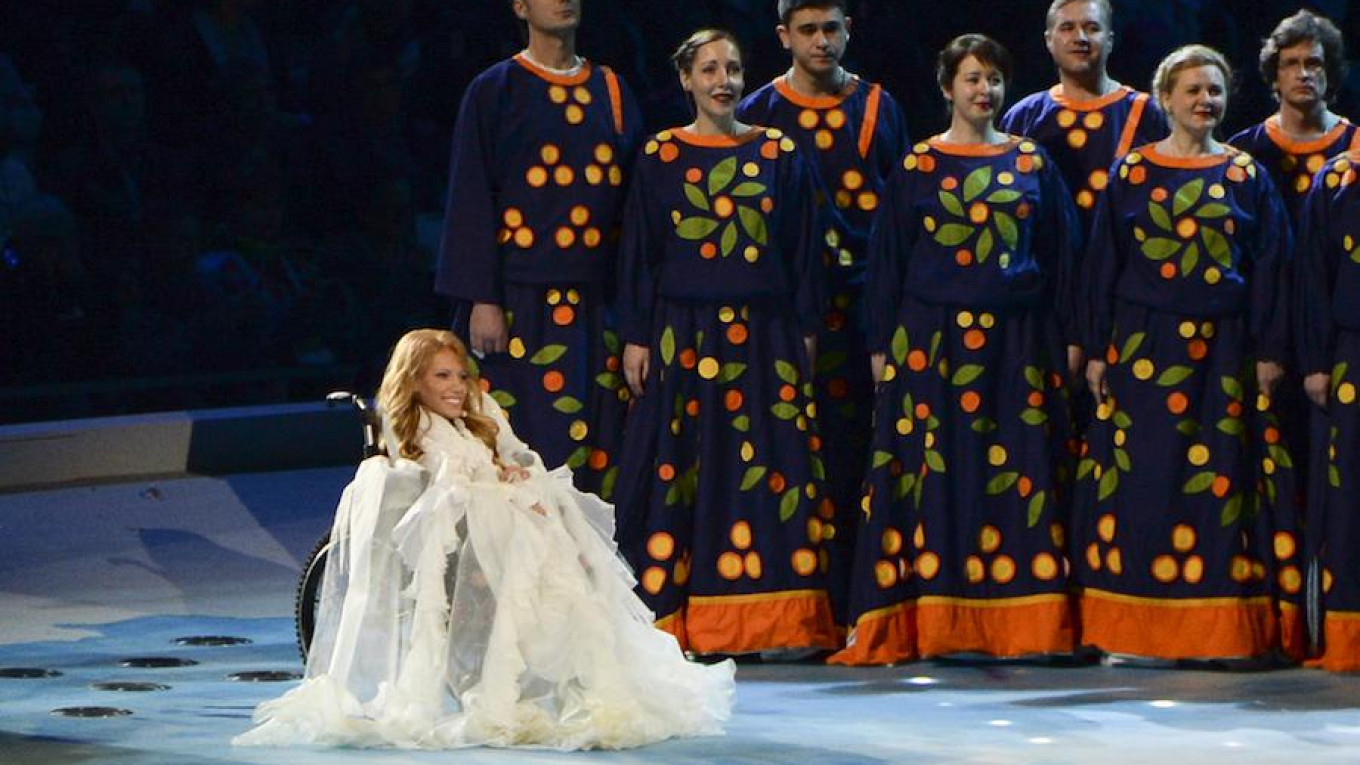

Samoylova was born healthy, but incurred a disability as a young child following a botched vaccination. She made a name for herself in 2013, on the “Faktor A” talent tv-show, where she came second. In 2014, she performed at the opening ceremony of the Winter Paralympics in Sochi. Her performances were hailed as an example of resilience, but she stayed short of making it big until now.

With the conflict between Ukraine and Russia nowhere near resolution, opinion at home is divided over whether Russia should participate in the festival at all. A Twitter poll by one of Russian state tv's flagship presenters Vladimir Solovyov had 68 percent of more than 7,500 Twitter users vote in favor of a Russian boycott.

Judging by reports from Kiev, Ukraine is not too keen either.

Old social media posts that have surfaced online show Samoylova has in the past defended Russia’s annexation of Crimea. She also gave a concert there in June 2015 — a red rag for Kiev, which classifies Crimea as occupied territory. According to Ukrainian law, it is reason enough to bar her entry to the country.

In a Facebook post, a spokesperson for the SBU, Ukraine's security service, said the organization was investigating the details of the Crimea visit and would make a ruling based on “Ukrainian law and national security interests.”

Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov has denied that the choice of a candidate who openly supports Russia’s annexation of Crimea is in any way a provocation of the Ukrainian authorities. “Everyone has been to Crimea, there is practically no one who hasn't been there,” he told Russian media. “It's an international competition and the the host country should follow international rules.”

In comments to The Moscow Times, The Eurovision song festival said the final decision would be taken by the Ukrainian authorities. It added: "We have had previous assurances from the Ukrainian authorities that, in the spirit of the event, all those who wish to attend the Eurovision and who pose no threat will be free to do so and their safety will be guaranteed."

In any case, some commentators argue, Kiev's hands are tied: Moscow would frame any attack on Samoylova as an attack on the disabled, they say. “The Kremlin will transform itself from a fortress of conservative values into a defender of human rights,” Metodichka, an anonymous news channel on Telegram popular among the liberal intelligentsia, wrote.

It would not be the first time Russian state media has galvanized people with a disability to claim the moral high-ground. When the International Paralympic Committee last summer announced it would impose a blanket ban on Russian Paralympic athletes over doping allegations, it was widely framed as a cynical attack on the innocent and defenseless.

“If they don’t allow Samoylova to enter Kiev because of her concert in Crimea, or if she is met by anti-Russian slogans or eggs are pelted at her, it’s clear in what terms Russian officials will start talking about it,” commentator Oleg Kashin wrote in an article in Republic.ru.

Meanwhile, life for disabled Russians is riddled with obstacles and stigma. With practically no infrastructure in place, they are often condemned to their homes, rendering them practically invisible. And some would prefer to keep it so.

In comments to the liberal Ekho Moskvy radio station, Soviet-era crooner Iosif Kobzon said Eurovision was “a tournament for healthy contestants,” and appointing Samoylova was ammunition for Russia’s rivals. “To give [people] a reason to say: the country is as [flawed as] its contestants, we can't do such things,” he said. About eighteen percent of a poll in the Komsomolskaya Pravda tabloid, one of many in the Russian media, said a different candidate should have been chosen.

Russia’s ambiguous attitude toward the disabled has been widely meted out in the national media only recently. The scandal was triggered by comments made by two famous judges on the popular TV talent show “Minuta Slavy” (Minute of Fame) following the performance of a dancer who had been left with one leg after suffering a severe road accident.

Panel member and prominent presenter Vladimir Pozner voted down Yevgeny Smirnov’s act suggesting his disability was being used as a “gimmick.” A fellow panel member, famous actress Renata Litvinova, proposed Smirnov use a prosthetic to make his disability “less obvious” and in order not to “exploit the topic.”

Following the public outburst, the two judges apologized in the next episode, saying they hadn't meant to offend, but Smirnov dropped out in protest.

Following the pick of Samoylova, many Russian commentators have speculated that Channel One, which broadcasts “Minuta Slavy” and also owns the rights to Eurovision, was trying to atone for the scandal. Clips of Pozner's apology and the clip of Samoylova's appointment both featured practically next to each other on its home page.

Perspektiva, a Russian non-governmental organization that defends the rights of disabled people, sees a silver lining to all the media attention. “The fact there’s dialogue around disability, that it has stopped being a moral taboo, is a huge step for Russia,” a spokesperson for the NGO Yelena Zaluchayeva, told The Moscow Times. Some political experts have even speculated that disabled rights may now become a platform for Putin’s 2018 presidential campaign.

Smirnov, the dancer, agrees Samoylova’s participation in the contest is a positive development — but for a different reason.

“Other countries have a completely different attitude to disability [than Russia],” he told the Komsomolskaya Pravda tabloid. “So those who will vote for her, will do so on the basis of Yulia’s art, and not her disability.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.