In the courtyard of the Tretyakov Gallery is a large pavilion that shelters a new, important work of art by the Russian artist Pavel Kaplevich. Kaplevich calls his work a “dialog” with Alexander Ivanov’s painting, “The Appearance of Christ Before the People.” Before you enter the pavilion, first go into the museum and make your way to Hall 10. That’s where Kaplevich began his journey, and where you should begin, too. And the journey starts with a story.

The Great Masterpiece of Russian Art

In 1833 a young Russian artist, fresh out of the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, went to Italy in search of a great idea. Alexander Ivanov, the son of a member of the Academy, had begun studying art at the age of 11 and was by then a well-skilled artist, if as yet uninspired. In Rome Ivanov studied the Italian masterpieces and dedicated himself to a study of the Bible. Finally he found what he wanted to paint: the moment when Christ appears to John the Baptist and a group of people on the banks of the Jordan River as described in the Gospels of Matthew and John.

Svetlana Stepanova, senior researcher in the Tretyakov Gallery’s Department of Painting of the 18th and first half of the 19th Century, described the subject of the painting as “a highly emotional moment — people are being baptized, see Christ and experience him for the first time. Ivanov, ecstatic, wrote his father that he’d found the ‘story that began all stories,’ the subject would unite his compatriots… His father wrote back, ‘it’s a wonderful subject, but how are you going to express it visually?’”

That was the problem that Ivanov would spend the next 20 years of his life trying to solve.

He began work in 1837, filling his damp Roman studio with dozens and then hundreds of sketches. Ivanov was at heart a realist; he needed to paint real people, places, trees, and hills. He traveled around the country looking for landscapes and models. He painted dozens of people for each of his characters; he placed his figures in different positions; he tried different colors for their robes; and he painted Christ over and over again, with different features and expressions, and once with the dove descending from heaven. By the time he brought his enormous canvas back to Russia, he would paint over 800 preliminary canvases.

Ivanov’s painting and his hundreds of sketches became the talk of the Russian art world. “Everyone knew that Ivanov was in Rome working for the glory of Russian art, painting his great masterpiece,” Stepanova said.

Finally, in 1858, 20 years after he began, Ivanov brought his work to his homeland. It was, the artist thought, unfinished, in part because he’d had problems with the varnish in his damp studio, which resulted in one character’s face — the slave — developing a green tinge. But all the same, he presented it first to the tsar, and then brought it to the Academy of Arts. The reactions of the Academy members, artists and public were varied. Some thought it was too brightly colored, or the characters were too Semitic, or the perspective was off. Ivanov’s father thought that the figure of Christ was too small and that there should have been signs of divinity. But the tsar liked it, and other critics immediately saw the painting’s brilliance.

Ivanov was distressed by the criticism, but unable to respond. He died of cholera 25 days after returning to his homeland.

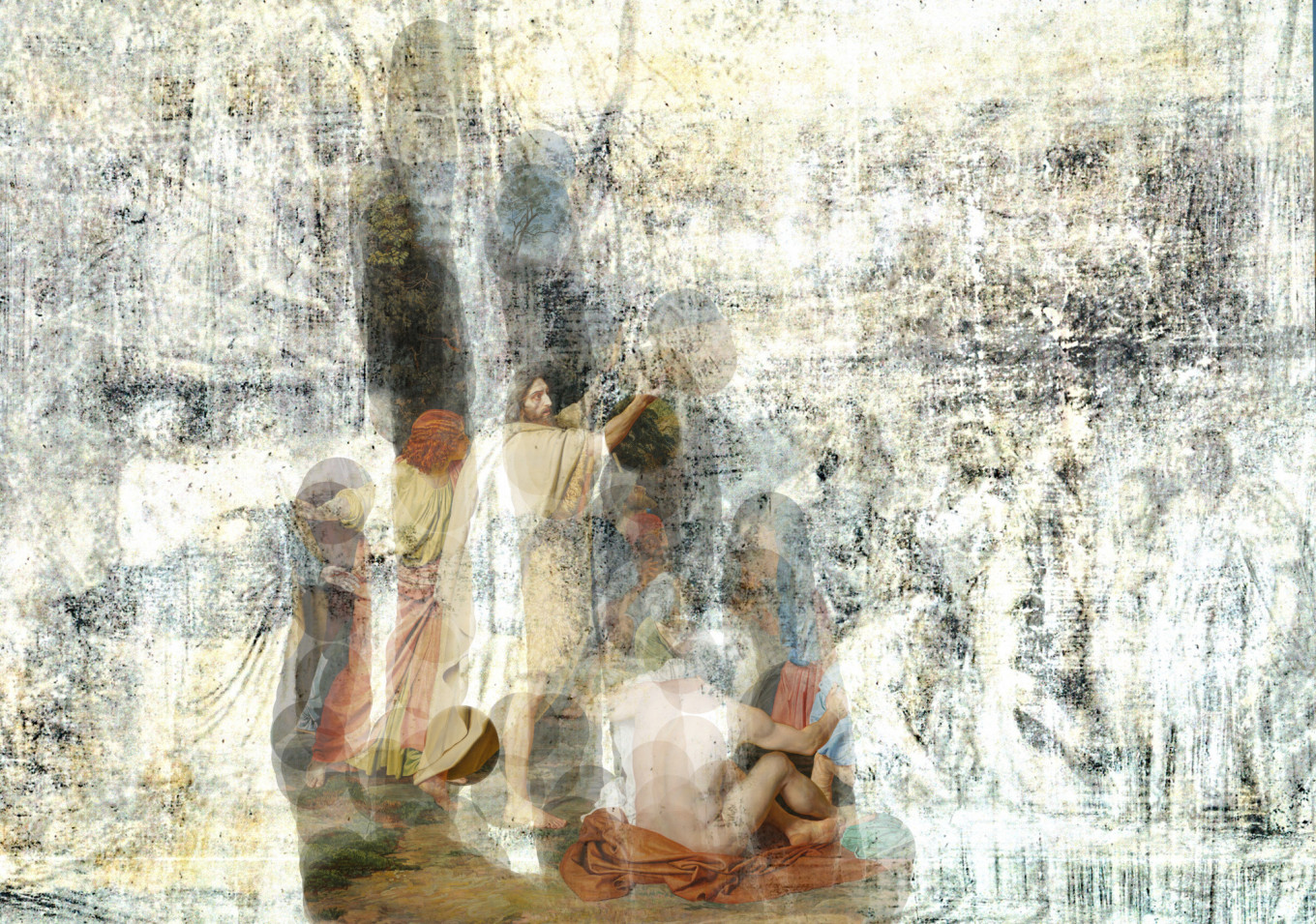

The Appearance of Christ Before the People

The enormous canvas covers an entire wall. John the Baptist in his “camel skin and leather,” as described in the Bible, stands by the banks of the Jordan. To the left are the future apostles. Along the river are men who have just been baptized, each expressing a different emotion. To the right — the group of Pharisees, Sadducees and soldiers, “quaking” in fear and awe.

Christ appears as a small figure in the distance. As Stepanova points out, “The Apostles didn’t tell us what Christ looked like, and here, too it’s not clear. Christ fits some of the iconographic images, but there is nothing definite about the portrait. Even though Ivanov worked with models, he sought to find the right balance between the real and the ideal.”

This monumental painting — monumental in size, in subject, in years painted, in psychological and historical detail — earned the canvas a special place in Russian artistic tradition, and it is commonly called “the main painting,” or “the greatest masterpiece,” or “the key work” in Russian art.

Painting With Viewers

When a painting is so celebrated, sooner or later other artists respond to it. The first artistic dialog with Ivanov’s master work is in the next hall of the Tretyakov Gallery: Erik Bulatov’s “Painting With Viewers,” completed in 2012 and recently presented to the museum by the Vladimir Potanin Foundation.

Bulatov has reproduced Ivanov’s canvas, albeit in peachier tones and on a smaller scale, but added the museum-goers, guides, art lovers and tourists milling about before the painting. The modern visitors stand, as it were, among the slaves, rich men, Apostles and Pharisees on the banks of the Jordan — and, of course, so do you as you stand before it, along with all the other bored, curious, indifferent, reverent and disapproving people around you. Bulatov plays with the notions of boundaries, reality and the imaginary, the dialog between art and audience. As Bulatov’s painted viewers and the physical viewers in the museum looking at the painting enter the work of art, Christ leaves the canvas to enter the reality of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow in the present day. It is an unnerving work — playful, critical, and slightly sly.

Kaplevich’s Appearance

Outside the Tretyakov Gallery in the courtyard is the third work to enter into a dialog with Ivanov’s masterpiece. Step inside the structure designed by Sergei Choban — something like a temple of stone — with doors that can be flung all the way open or almost closed shut to change the light and ambiance. Stand or sit on one of the beanbag chairs. Be still. And watch.

Pavel Kaplevich, an artist and theater producer, has created the work that appears on the enormous screen inside the pavilion. It is called ПроЯвление, a play on the title of Ivanov’s canvas, in which the appearance of Christ is Явление. Kaplevich’s title could be translated as “about the appearance,” but the word проявление also means a demonstration, expression, performance, testament and even the development of film.

The work is all of the above. On the canvas — precisely the size of Ivanov’s — the 19 versions Ivanov made of the painting appear, become clearer, and then fade away; figures move across the canvas, pause, brighten and then depart; Christ appears, disappears, returns with the dove of the spirit descending upon him. As the images change, the seams in the cloth seem to twist and turn like cracks in the wall to let in ribbons of light.

Kaplevich has re-imagined Ivanov’s canvas as if it were created in different eras by different techniques. It is a tapestry with bold colors that hangs on the wall for 500 years and then fades into nothingness. It is a Florentine mosaic, a bas relief in stone, a graphic drawing in black and white. As the images pass by, they are accompanied by music, the sounds of rustling leaves, birdsong and the tapping of twigs (created by the composer Alexander Manotskov). The full performance —the development of the theme and images — takes just over four minutes. “The most important moment,” Kaplevich told The Moscow Times, “is when one image hasn’t gone and the next hasn’t appeared… the ‘subtle matter’ can be seen at those moments.”

Ivanov’s painting was, in the end, about the people who saw Christ and their response. Kaplevich’s “Dialog” with Ivanov’s painting continues to tell the same story. “Everyone sees Christ in his own way, the way he wants to see him…. or doesn’t want to see him, doesn’t believe he exists,” he said. “It’s like a film about people responding to Christ over time.”

“There was an element of the miraculous depicted in the original painting,” Kaplevich said, “I didn’t just want to depict a miracle. I wanted the theme of the entire work to be belief in a miracle. So the miracle of the Appearance of Christ was what moved me to work my own miracles.”

How Kaplevich works his miracles remains his artistic secret. The canvas is roughly textured, and three or more layers of images seem to be on it. But that, Kaplevich said, is an illusion.

Even for the artist, some elements of the finished work remain a mystery. Kaplevich described the process of installation. “The first idea was for it to look like a tapestry. But when we came to install it… it looked like it was a painting in a church. When we put it up, canvas stretchers along the edges appeared. Where did they come from? They aren’t painted. They aren’t there, but you can see them.”

The work — all of it: the pavilion, canvas, lights and sound accompaniment — is going to Vatican after Russia, and perhaps from there to other parts of the world. But nowhere else will viewers be able to see the original painting, the first artistic response to it, and then Kaplevich’s “Dialog.” See it while you can. It closes on September 15.