About half an hour from the western outskirts of Moscow, the grays of Russian suburbia give way to a jagged horizon of shiny glass, concrete and abandoned building sites. A series of giant wooden pencils emerge, bearing the insignia "Skoltech." The curious art installation signals arrival at the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, brainchild of former President Dmitry Medvedev, and Russia's much-hyped entry into the 21st century innovation race.

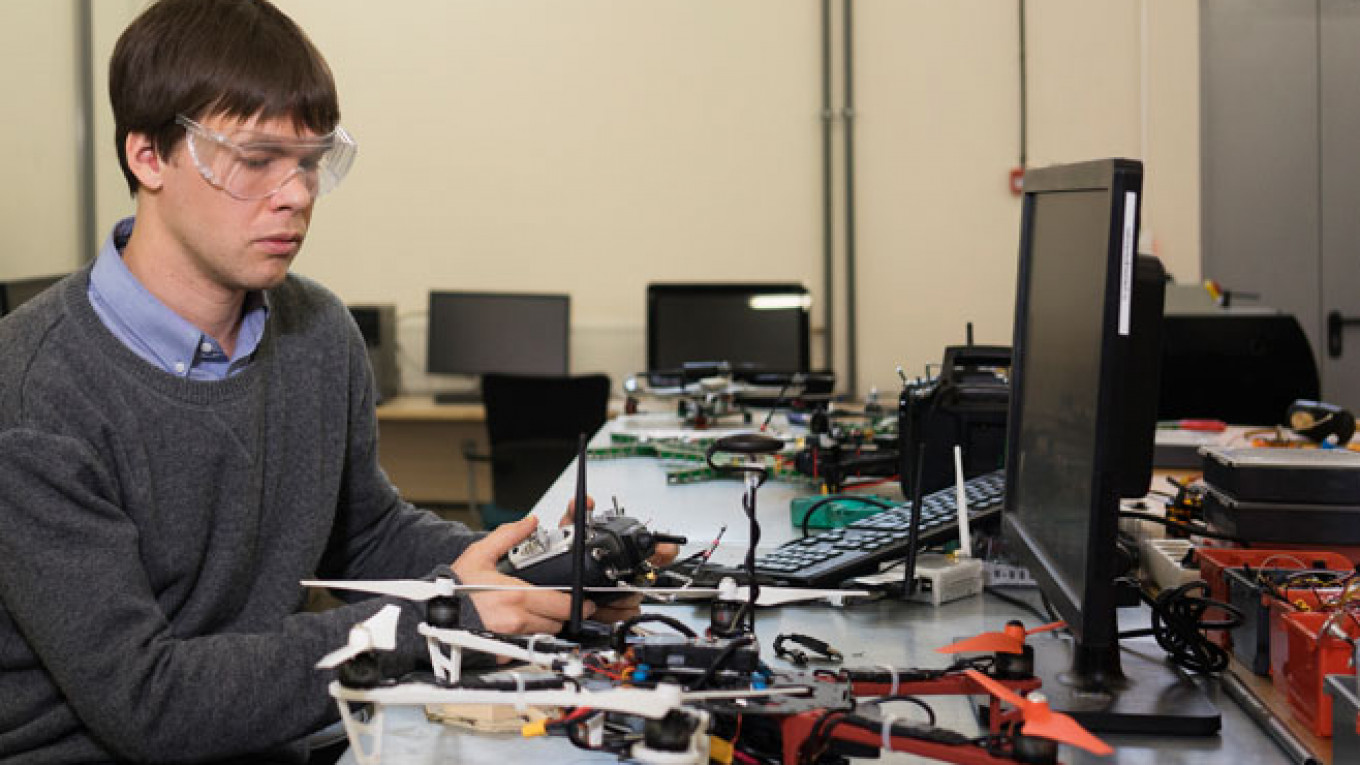

Standing beside one of Skolkovo's futuristic buildings is American engineer Brendan Smith. A graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Smith heads Skoltech's student research laboratory. Smith decided to come to Russia five years ago, after a period working in the U.S. aerospace industry. He had offers for other work — one from Australia springs to mind — but a longstanding curiosity about Russia brought him east.

In recent years, the Russian government has worked hard to attract foreign researchers to the country. Smith is a poster boy for the strategy, but, overall, the record of such programs is mixed. At one point, foreigners came in great numbers, attracted by high salaries and excellent career prospects. But then came Ukraine, Crimea, sanctions, a low oil price and worrying economic malaise, and a great many left.

Skolkovo was not immune from the process. In 2014, Dutch geneticist Anton Berns left the institute following the downing of Flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine. Last year, he was followed by two other professors, material scientist Zafer G?rdal and computer engineer Raj Rajagopalan, both American.

In September, Skolkovo president Edward Crawley announced he too would be leaving. The official reason was that his five-year contract was up for renewal. Unofficially, as much of the local media reported at the time, the impact of sanctions on Skolkovo's long-term future was to blame.

Smith believes his colleagues left for "personal" reasons, and sees no reason to follow them. He has married a Russian, and says no part of his research has ever been compromised by politics: "It's just the media from both sides — in the United States and Russia — exaggerating every single issue to sell newspapers."

The American academic Kendrick White was working at Nizhny Novgorod State University when Russian state television aired a report accusing him of working as an undercover agent, in June 2015. He had lived and worked in Russia for nearly 20 years.

Some foreigners have had serious difficulties, however. In June 2015, Russian state television aired a scandalous story claiming that an American academic working at Nizhny Novgorod State University was an undercover agent, working to spirit Russian specialists away to the West. The academic in question, Kendrick White, was, in fact, a venture investor and vice rector of the university, and he had lived and worked in Russia for nearly 20 years. He had even given an interview to the journalists, only to see his views distorted in a selective editing process.

White was vacationing with his family in Florida when the documentary aired, and was unprepared when two days later he received the news that he was no longer required at the university. In a press release on their website, the university claimed his job no longer existed following "structural changes in management." Such an unlikely explanation caused a media scandal. Perhaps more significantly, Education Minister Dmitry Livanov publicly criticized the university's decision. In the end, the university backtracked and invited White back to Nizhny Novgorod. The academic has studiously avoided making statements to the media since.

"There are bad stories, of course, but overall I think things are moving in a positive direction," says Maria Ditkovskaya, head of the international department at St. Petersburg's ITMO university. Ditkovskaya's university is one of a network of 21 research institutions that have implemented the Russian government's "5-100" strategy, a 2013 program that seeks to improve the standing of Russian universities in world education rankings. One of the main aims of the program is to increase the amount of foreign specialists working in research institutions.

Ditkovskaya says her university has seen no change in the level of foreigners applying for vacant positions. Nearly 400 candidates applied in the last round of applications, she says. Successful candidates all have a minimum Hirsch index score of 10, indicating a high level of research productivity and international impact.

Gabriele Saleh, an Italian theoretical chemist,moved to Russia to work alongside Artyom Oganov, a world-renowned expert in materials science.

Ryan Burg, assistant professor of business at Moscow's prestigious Higher School of Economics, agrees the country is slowly becoming a better place for foreign researchers. "A lot of work is being done to make Russian universities places where foreigners can come, work and make contributions," he says. There are still differences, of course, but, says Burg, the negative moments are usually balanced by positive ones. So, for example, while HSE lacks a clear organizational culture, its researchers enjoy much more autonomy to focus on what they see as important.

"Many of my Western colleagues are obsessed with the 500 largest international companies and write about what Apple does or what Google does," says Burg. "I think it's more interesting to see what happens outside those major corporations, so that's what I do."

Traditionally, the things that have kept foreign specialists from applying to Russia are insecurities over language, safety and finance. Now, political concerns are playing a bigger role. "Russia's insistence on creating a narrative that its closest friends in the world are Syria, Iran and North Korea has caused problems for academics," says Burg. "None of these places have serious universities. If Russia wants its PhDs to matter internationally, it needs to develop better relationships with the United States and Western Europe."

Money is also becoming an issue. Following a spectacular fall in the value of the ruble over the last two years, local salaries have become uncompetitive. Gabriele Saleh, 31, a theoretical chemist from near Milan, says it is now hard to attract the best and brightest: "200,000 rubles is a huge monthly salary for Russians, but if you offer such salary to someone coming from the United States, he will calculate and see that it's $3,000. Of course he will say no."

Saleh says his own decision to move to Moscow was motivated not by money but by the standard of research here. He had long followed the work of future boss Artyom Oganov, a world-renowned expert in materials science and crystallography. In 2014, he found out Oganov had won a grant to open a new lab at the Moscow Institute for Physics and Technology, so he sent in his resume and was invited for a Skype interview. A few months later he flew to Moscow and began assisting Oganov in his cutting edge research on computational material discovery.

Saleh says Russia has already made a considerable investment in science, and the results will only be evident in a few years. "If they keep the investment up, Russia could be a world leader," says Saleh. "The question is whether they have a long-term plan or are just investing the oil money. I suspect it's the latter".

Ryan Burg, an assistant professor of business at Moscow's Higher School of Economics, believes that Russia is slowly becoming a better place for foreign researchers.

Even if such long-term plans exist, it is unlikely they will survive Russia's sobering new economic reality. A contraction in global trade and demand for raw materials, a sharp fall in the oil price and a 3.7 percent annual decrease in GDP mean the government cannot avoid cuts, and scientific research is one of the lesser-protected areas of government spending.

Last Tuesday, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev convened a special expert council on innovation to discuss the government's response to the new climate. The meeting was closed to journalists, but afterwards Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich confirmed that the government was now considering restructuring or liquidating three of its flagship innovation projects — Skolkovo, Rosnano and the RVC venture capital company.

The disclosure marked a departure from Dvorkovich's position of just a year ago, when he described Skoltech as "the most difficult startup in Russia … with no right to fail."

Skolkovo's Brendan Smith is not unduly concerned by the threat. He says the organization will always be needed because it pushes the boundaries of science: "Even if they close it down, they'll open another organization doing exactly the same thing. It's what the Russians always do."

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.