On Wednesday, at about 17:42 Moscow time, the Russian space agency Roscosmos, in partnership with the European Space Agency, will attempt something it has failed to do since the heyday of the Soviet space program in the 1970s: landing an unmanned probe on the surface of Mars.

The mission, known

as ExoMars, has been in the works for years. It is a two-phase

cooperative project with ESA, a conglomerate of European national

space agencies. Wednesday's mission is considered a demonstration run for

a bolder mission slated for 2020.

Despite being one of

the most decorated space programs in history, Russia has had an especially challenging time with Mars. The last successful mission was

conducted in the early 1970s, but every attempt before and after has

failed. The United States, meanwhile, has seen great success there.

The mission is

likewise significant for the Europeans, who have never landed a

successful probe on Mars. The last European mission, Beagle 2, landed

but never deployed its solar panels, and so contact with the probe

was lost before it reached the planet's surface.

ExoMars, a 1.5

billion euro ($1.65 billion) project, was conceived as a joint

European-American mission to Mars. But in 2012, U.S. President Barack

Obama adjusted his space agency's course, and NASA withdrew.

Roscosmos, eying an opportunity to reach Mars, stepped in to assume the

burden.

However, Russia's

involvement is heavily stacked toward the later, 2020 ExoMars

mission, which will feature a Russian-built landing vehicle carrying a European rover to explore the

Martian surface. Russia's main contribution to this first mission is

providing the rocket that launched the spacecraft in March.

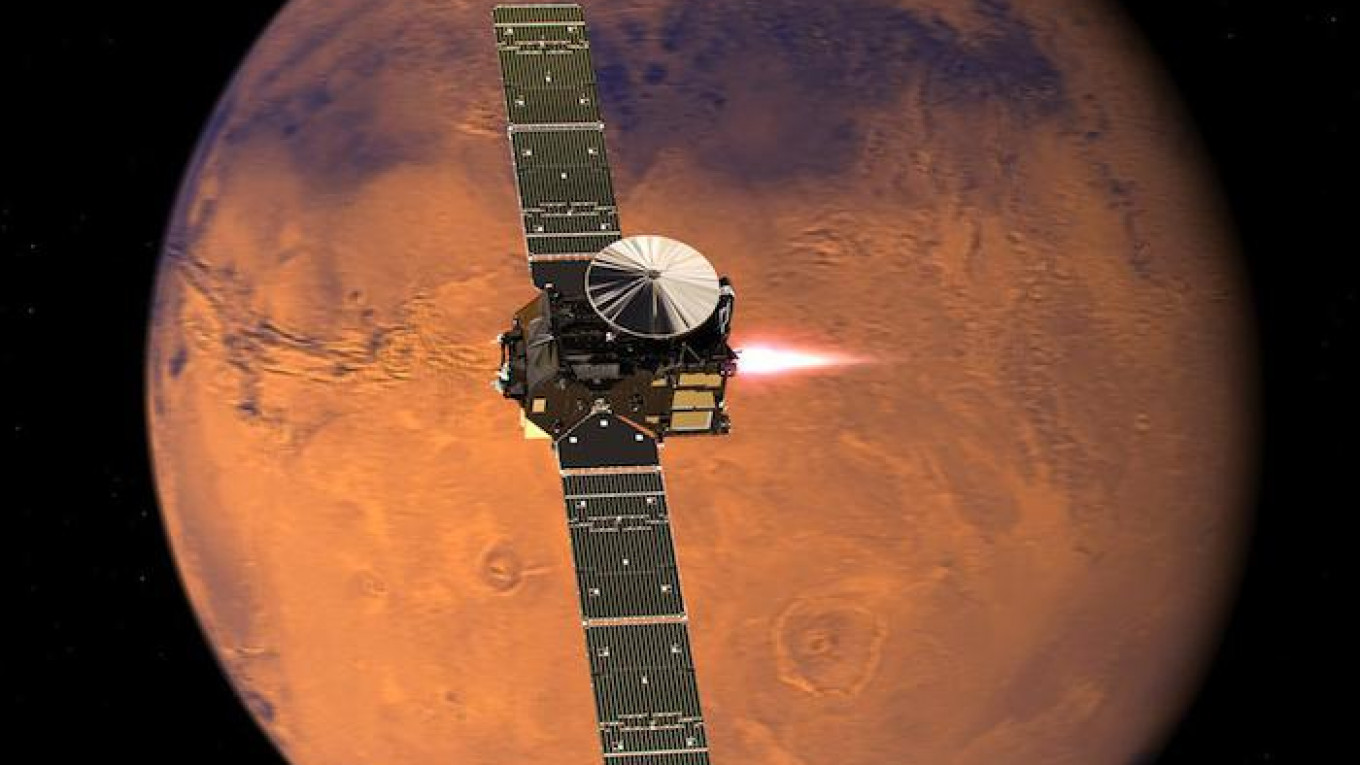

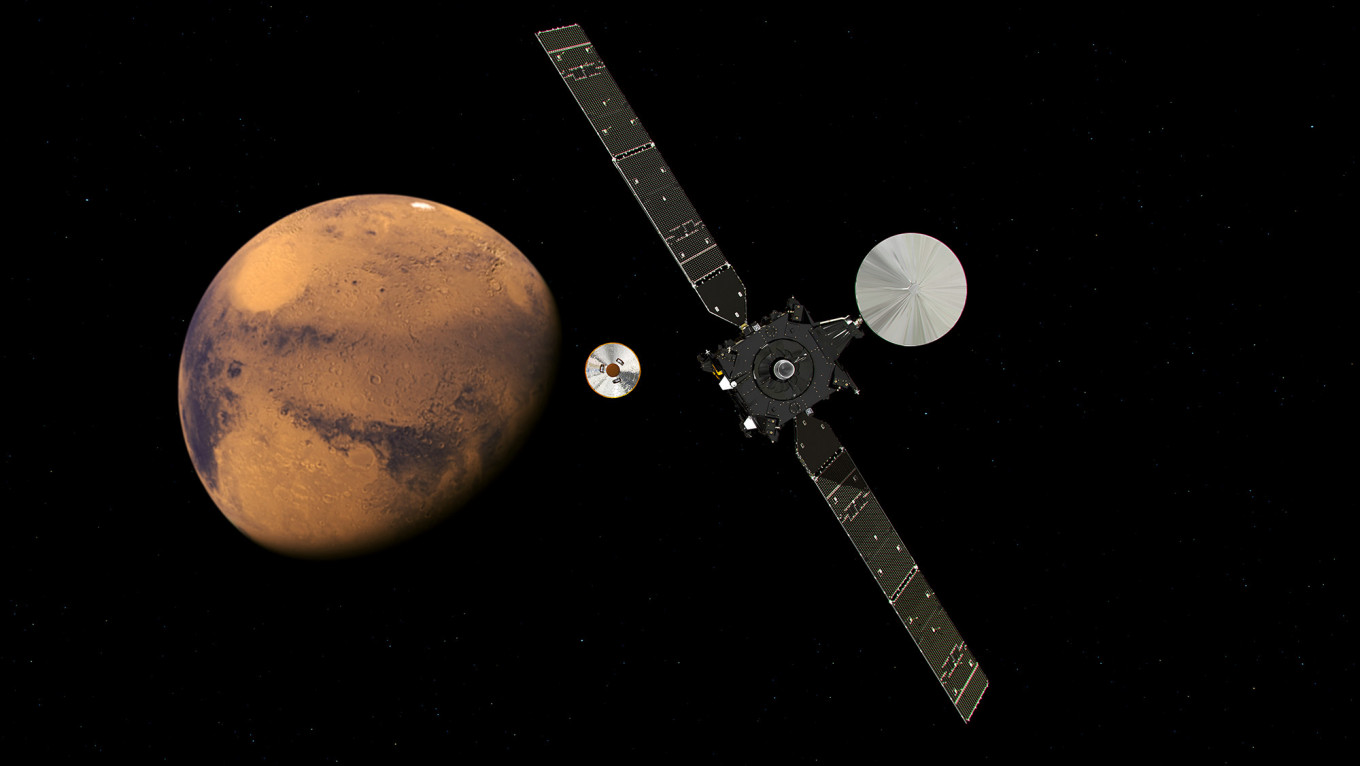

Phase one of the ExoMars project consists of two vehicles. The core spacecraft is known as the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), and is the primary component of the first stage in the ExoMars project. A second module, the Schiaparelli lander, hitched a ride to Mars aboard TGO.

The two spacecraft have different destinations, and on Sunday they parted ways. TGO is aiming to insert itself in Martian orbit, a maneuver that will require the orbiter to fire its main engine as it passes by Mars. This allows the spacecraft to slow down enough for Mars gravity to grab it.

If TGO's maneuver

fails, it will fly off into deep space. The maneuver is scheduled for

16:04 Moscow time, according the TASS news agency.

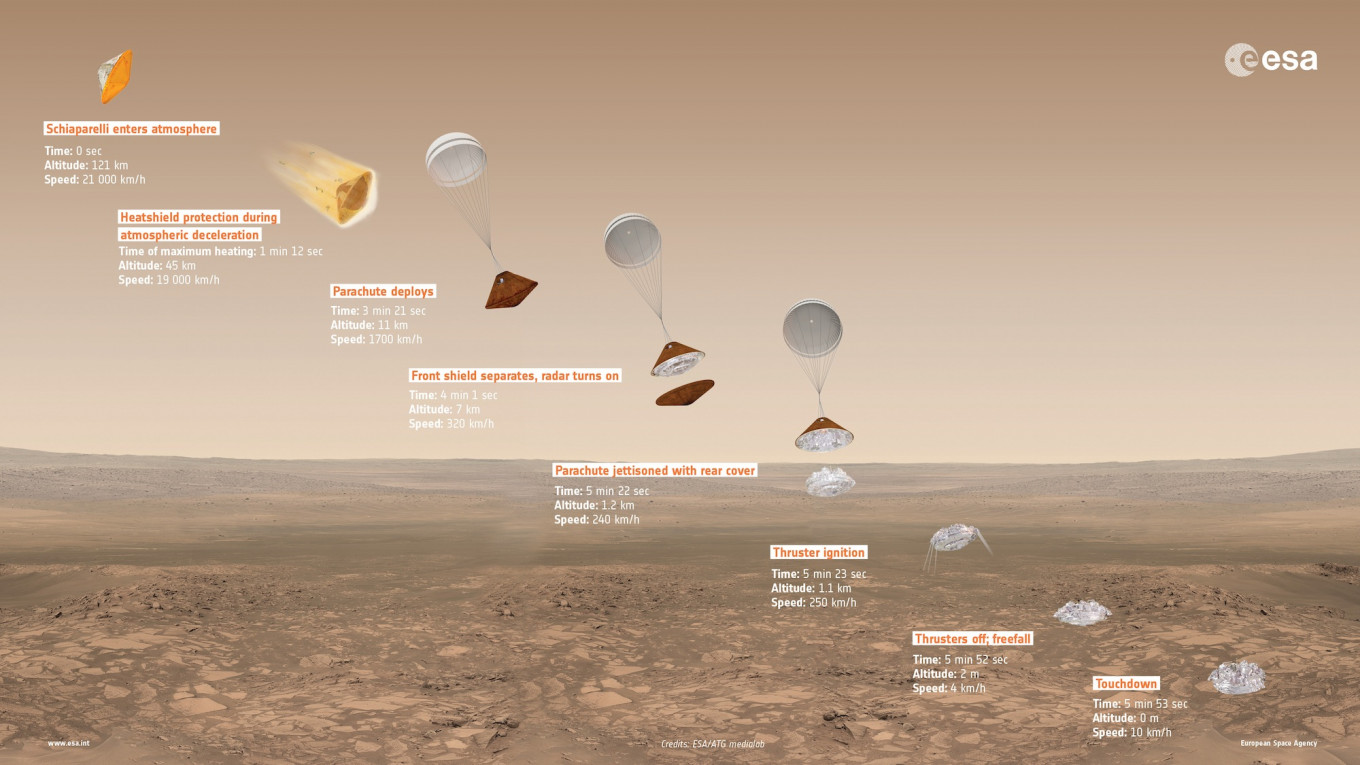

Meanwhile, the more dramatic maneuver will be conducted by the Schiaparelli lander, which is hurdling toward the Martian surface. If everything goes according to plan, Schiaparelli will hit the Martian atmosphere at a speed of 21,000 km/h at an altitude of about 121 kilometers.

For three to four

minutes after first contact with the Martian atmosphere, Schiaparelli

will use the atmosphere to bleed off speed. The lander is encased in

an outer shell that will absorb the heat generated by entering the

atmosphere.

Once Schiaparelli has slowed to 1,700 kilometers per hour, a parachute will deploy. At this point, the probe should be 11 kilometers off the Martian surface. Forty seconds later, the bottom half of the Schiaparelli's outer shell will eject. Once the parachute has slowed the craft to 250 kilometers per hour, the parachute will eject with the rest of the outer shell.

At this point,

Schiaparelli will be open to the elements and in a state of free

fall. The probe will quickly activate landing thrusters to control

the remainder of its descent to the surface. At an altitude of 2

meters, it will briefly hover before cutting thrust and dropping to

the ground.

“The touchdown

speed will be a few meters per second, with impact absorbed by a

crushable structure similar to the crumple zone in a car,” an ESA

explainer of the landing sequence says. All told, the journey from

space to ground will last no more than six minutes.

But the landing will be complicated by a Martian storm that could not have been predicted when the mission's timeline was set in March. Schiaparelli will be falling into a dramatic Martian sandstorm.

“Its nerve wracking, but if we can land through a global dust storm, we can make it anywhere,” Thierry Blancquaert, ESA's lead engineer on the project, told Bloomberg. “We built Schiaparelli taking that possible storm into account. We added an extra layer on [the outer shell] to counter erosion and made sure it could handle the wins.

If successful, the landing will be a big win for both Roscosmos and ESA. Schiaparelli has been designed as a technology demonstrator for the larger, 2020 ExoMars mission, which will feature a Russian-built descent module delivering a European-built rover to the surface.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.