As Russia has worked to convince the world that its military power is growing, it has concealed its costs in terms of blood and treasure.

But newly revealed statistics show surprisingly low casualties despite engagements in Crimea, eastern Ukraine and Syria.

It was the latest evidence that President Vladimir Putin's military strategy is far more calculated than his predecessors, who were willing to win at all costs.

Boris Yeltsin's losses in Chechnya gutted his public support and the Soviet Union's costly, failed Afghanistan adventure helped speed the end of an empire. Putin's position is far more secure, which makes his approach to war all the more difficult to explain.

Russia has not reported active-duty casualties since 2010 even as it expanded its military operations on several fronts. In 2015, Putin was accused of trying to hide losses in eastern Ukraine, where Russia stubbornly denies military involvement, by classifying data on losses incurred in "peacetime military operations."

This week, the daily newspaper Vedomosti discovered the casualties figures on the Russian government procurement website.

In October, Sogaz, an insurance company owned by a group of investors close to Putin, won the tender to insure Russian military personnel against death and injury. Everyone in active service — conscripts, professional contract soldiers, officers — is insured. In 2016, that meant 1,191,095 people.

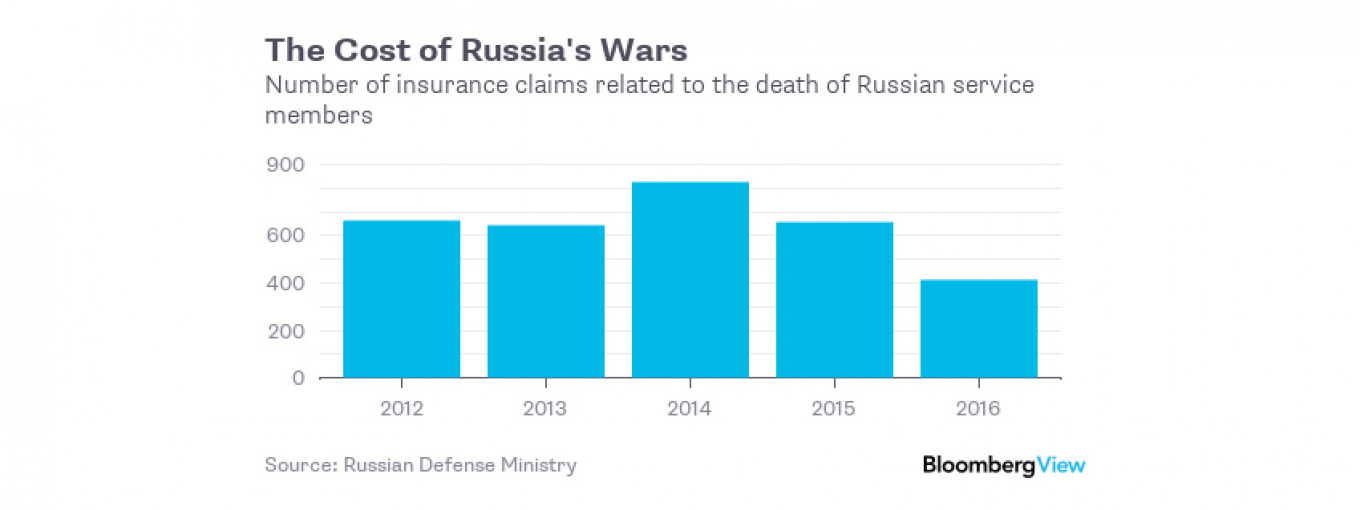

Along with the requirements and probability tables, the Defense Ministry, which organized the tender published the number of insurance claims made in 2012 through 2016. Of these claims, 3,198 were related to deaths. The deaths didn't necessarily occur the same year as the claims were made, but the count should be close enough to the actual number of casualties.

These fall far short of earlier losses. In 2000, for example, the Russian military lost 1,310 people in Chechnya, according to official statistics.

In 2014, Ukraine accused Russia of sending troops to stop it from crushing two pro-Russian, separatist "people's republics" in its eastern part.

Regular Russian troops apparently did show up in eastern Ukraine at crucial moments of the conflict, such as when the Ukrainian military was surrounded at Ilovaysk in August and September, 2014, and when they were crushed at Debaltseve in January and February, 2015.

According to the Ukrainian Defense Ministry, it lost 432 service members in these two battles. If the small peak of Russian casualties in 2014 indicates the Ilovaysk episode, and if about 650 deaths a year in 2012 and 2013 are standard peaceful-year numbers, Russia lost about 170 service members in the Ilovaysk intervention. The Debaltseve casualties were statistically negligible.

So clearly were the regular military's losses in Syria, where Russia began a largely aerial operation in support of President Bashar Assad in September, 2015.

When Putin came to Assad's rescue, many Russians — including some Putin supporters — feared he might get bogged down there, as the Soviets did in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

The Soviet Union lost more than 15,000 people in the 10-year war — enough for the deaths to register on most Russians' radars.

Nobel prizewinner Svetlana Aleksievich described the grief and the anger in her 1989 novel, Zinc Boys. In terms of military casualties, however, Putin's Syrian campaign has cost his regime remarkably little, and now that the fighting is almost over, any damage to his domestic standing is highly unlikely.

The Russian military tradition — at least in the 20th-century wars — wasn't about keeping soldiers alive but about achieving goals at any price. The current numbers indicate a change — but perhaps not an entirely positive one.

Under Putin, Russia fights its wars in a different way.

In Ukraine, the separatist forces, consisting of Ukrainian nationals, Russian nationalist volunteers and mercenaries, bear the brunt of the losses in a war that has already killed more than 10,000 people.

In Syria, the Russian boots on the ground — as opposed to planes in the air — weren't, for the most part, regular service members but fighters of the Wagner — a private military company run by Dmitry Utkin, a former Russian military intelligence lieutenant colonel.

Its 6,000-strong mercenary force, not all of it Russian, has reportedly taken part in the Ukrainian action, too, including the Crimea takeover. There's only anecdotal information about Wagner's losses, though they would have far less political significance, of course.

As Putin increased and rearmed the Russian military, he has also embraced the concept of hybrid war, shifting much of the burden onto the shoulders of irregulars.

In part thanks to that shift, Russia's military losses in 2014, the worst of the last five years, only reached 68.8 per 100,000 — significantly less than the 88.1 service members per 100,000 the U.S. lost in 2010, the last year for which data are publicly available from the Defense Casualty Analysis System.

Contrary to its well-established practice, the Russian Defense Ministry didn't try to deny the casualty numbers after Vedomosti unearthed the tender documentation.

So perhaps the leak wasn't accidental: Putin is preparing to announce his bid for a fourth term as president, and the relatively small losses should help him show off his prowess as commander-in-chief.

Still, they won't justify Russia's participation in the destruction of Ukraine or the human, economic and diplomatic cost that disastrous Putin decision has imposed on Russia itself.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru. For more columns from Bloomberg View, click here.

The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.