They can’t compete with Mexico’s boisterous sombrero-clad fans or with Iceland supporters’ Viking clap. But even though China isn’t playing in this year’s World Cup, it is ahead in another category.

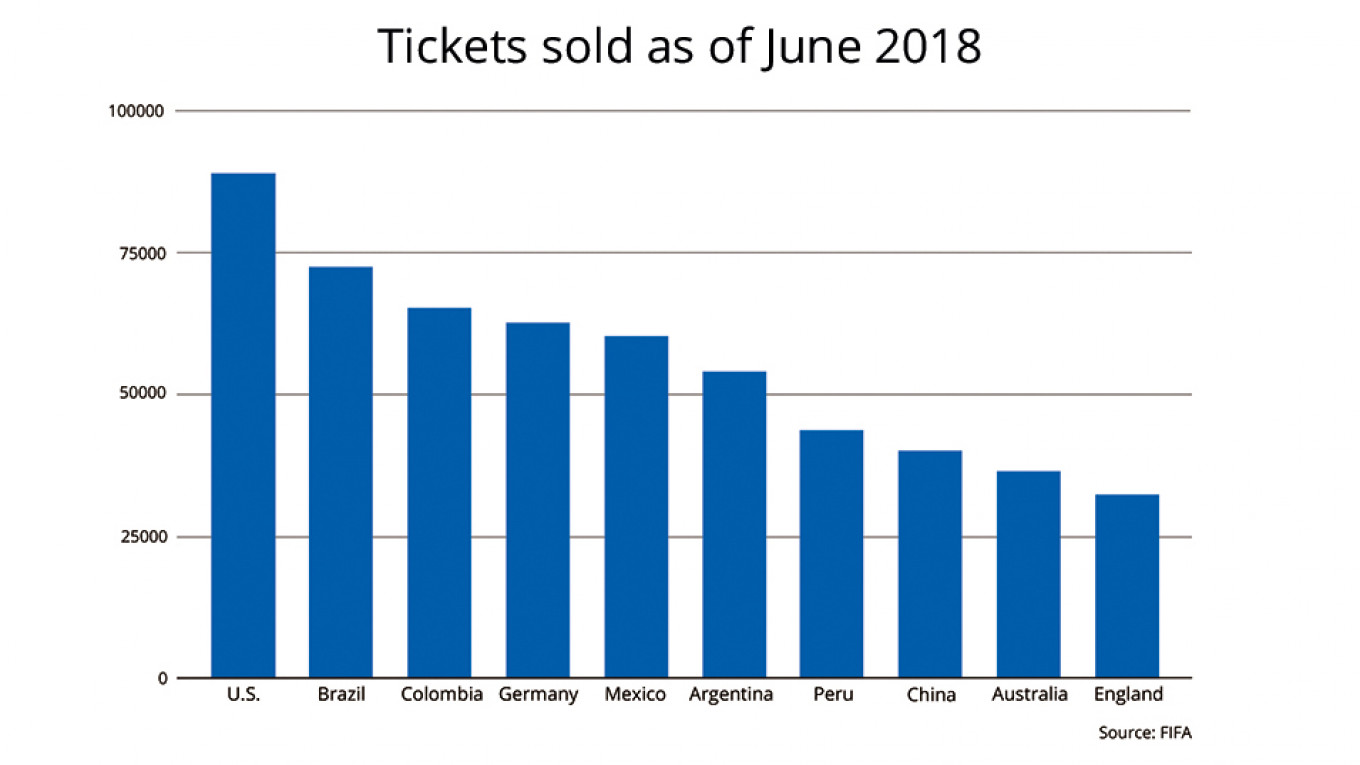

Some 60,000 Fan IDs have been issued to Chinese passport holders, Russia’s Communications Ministry announced in late June, putting the country in second place behind Russia in the number of fans attending matches. To put it in perspective, number three on the list, the United States, was issued 39,000 Fan IDs.

Many of those football fans are also shelling out.

According to Shankai Sports International, an exclusive agent in China selling World Cup tours, 10 percent of an estimated 40,000 tickets bought by Chinese fans this summer are in the VIP category.

“Chinese guests always try to get tickets to the most important matches and to buy the best seats,” Yekaterina Chelik, head of the Moscow-based Turne tour company, told The Moscow Times ahead of the tournament.

A new trend rooted in history

According to FIFA, the precursor to the modern game that millions around the globe are glued to this month dates back to China in the second and third centuries.

The story goes that during the Han Dynasty, military personnel would kick a leather ball stuffed with feathers through an opening into a small net. Hands were not allowed.

Despite this legacy, football in China has long played second fiddle to basketball. It is only in recent years that the people’s game has been given a new shot in the arm. And now, the culture of watching football is spreading like a wildfire in China with fans gathering in restaurants and pubs to watch matches.

“If you pass by the Workers’ Stadium [the main stadium in Beijing] when the matches are taking place, there are tents outside the stadium and people are selling souvenirs,” Viktor Kipriyanov, a Russian businessman who lives in Beijing, said. “It’s something new. It’s cool.”

In part, this surge in popularity is the product of politics. President Xi Jinping is a huge football fan and the sport has seen a large injection of state funding in infrastructure, planning and status in recent years.

Foreign stars, including Argentina’s Carlos Tevez and Ezequiel Lavezzi, Brazil’s Oscar Ramirez and Nigeria’s Odion Ighalo have all been lured to the Chinese Super League with huge paychecks. (Portugal star Cristiano Ronaldo reportedly declined a $105-million offer to play for a Chinese club.)

China’s football efforts, however, have yet to pay off — despite being an Olympic powerhouse, the country places 75th in FIFA’s ranking. But that has not dimmed the enthusiasm of Chinese fans flocking to Russian stadiums to see the best teams and players in the world battle for the golden trophy.

What makes this World Cup particularly enticing for Chinese fans is that, for the first time in 16 years, it is taking place in a country which borders China and with which it has cultural links.

Russia has long had a pull for the older generations in China, many of whom studied Russian history and language in school. “Growing up, my parents would read Russian novels, watch Soviet movies,” said Ellen Zhan, an entrepreneur from Beijing. “It was their dream destination when they were teenagers.”

Some 1.5 million Chinese tourists visited Russia last year, according to the Chinese Embassy in Moscow. Most of the visitors are middle-aged and part of a tour group, the tour operator Chelik said.

With the World Cup attracting a new demographic of Chinese tourists, those in the tourism industry hope to show that Russia can also be a destination for younger travelers, including those traveling by themselves or as part of small, informal groups rather than as part of organized tours.

Feng, 29, who declined to give his last name, bought his ticket for Iran’s match against Portugal in the World Cup group stage on Tabao, the Chinese version of eBay. In part, he said, the trip was a chance to see his favorite player, Cristiano Ronaldo, in action.

Feng said the simplified visa regime in place during the tournament had encouraged the other Chinese tourists he met in Saransk to pursue their dream of experiencing Russian history and culture.

One fan he met in Saransk told him he worshipped Mao and communism. “He came to Russia to follow in the footsteps of the ‘great forefathers’ of communism,” Feng added.

His own ambitions were simpler, he said. “Apart from football, I am just fulfilling my own dream, which is to fill my passports with stamps.”

Russian tour operators hope to see more tourists like Feng in the future. “We need to put all our efforts into drawing in young tourists,” Chelik said. “We are trying to entice athletes, fans of extreme sports and tourists looking for unconventional vacations to travel to Russia.”

Social media storm

Helping Chelik to achieve that aim is social media. WeChat and Weibo, the Chinese versions of Instagram, are popular ways for Chinese visitors to share pictures from their travels in Russia — and the World Cup is no exception.

Zhan, the entrepreneur, says that because everyone in China loves to share their holiday photos there will be a “significant spike” in interest in Russia even after Chinese tourists return home. “We are confident that its effect will increase the tourism flow even in 2019,” she told The Moscow Times.

Yuen Hauwing, a football fan from Hong Kong, says the thousands of World Cup photos will be shared widely by rich Chinese fans as a way of showing off their status. “Nowadays, being at the World Cup is more like a VIP event rather than a sports competition,” he told The Moscow Times. “It’s like a carnival.”

Xiaoqing-He contributed reporting.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.