Prior to the State Duma elections, everyone was talking about the imminent dismissal of Alexander Bastrykin, head of the Investigative Committee. Media reports said the decision had already been made, with the dismissal delayed until “after the elections.”

Bastrykin’s departure is in keeping with the major restructuring of security and law enforcement bodies that began back in March.

But his dismissal barely changes the larger picture: Both Bastrykin and his department were significantly weakened in the current restructuring process, and later by the high-profile arrests of senior investigators.

Bastrykin’s was not the only security structure to have been weakened. Some, such as the Federal Guard Service and the security services for the president and customs, saw a change in leadership. Others such as the Federal Security Service, Interior Ministry, and now the Investigative Committee, underwent a cleansing of second-tier management. The Federal Migration Service and Federal Drug Control Service were eliminated altogether.

The restructuring of the siloviki — loyal strongmen from the security services — is nearing an end, with the final chords set to sound after the elections. At the same time, the remaking of the political bloc has only begun. It is not so much that President Vladimir Putin has a grand plan for renewing the ruling elite, as much as he is responding to what the situation demands.

Russia’s leaders have unwittingly driven themselves into two traps.

The first is the trap of political legitimacy. The Kremlin is running out of ways to maintain the military-autocratic legitimacy of the ruling authorities. It cannot play the “Crimea card” a second time, and opinion polls indicate that the people care little whether Russia achieves a real or alleged victory in Syria. They are far more concerned about the standard of living at home, and the public mood is becoming increasingly isolationist.

This means the Kremlin must somehow restore its legitimacy. But the only way the national leader can stand for elections without compromising his hold on power is if nearly 100 percent of the voters turn out and vote for him — as autocratic Central Asian leaders orchestrate their elections. Otherwise, Putin becomes a weak ruler, and not a strong leader who can boast a mandate from the people.

Unfortunately, Central Asian-like results are difficult to achieve in Russia. Both the people and their government remember the mass protests of 2011-2012. Furthermore, the political machines which might have achieved sky-high voter turnout and support have been largely dismantled in the regions.

There are two ways out of this dilemma: either Putin puts forward a hand-picked successor to run in the next presidential elections, or he turns the elections into a plebiscite, thus enabling him to combine autocratic with electoral legitimacy.

The second trap is the excessively long interval between the current Duma elections and the presidential elections in 2018. If leaders wait another 18 months before implementing essential but painful economic reforms, they will exhaust the government’s financial reserves — something they would like to avoid.

Here, too, the authorities have two options: end the confrontation with the West and borrow money there to buy time until 2018, or hold early presidential elections.

In the latter case, Putin would have to either carry out modernization in some form, even authoritarian. Or he could finish building his authoritarian system, replete with a cleansing of the elite.

Either option would ruin the status quo, which would inevitably provoke serious resistance from the ruling elite. The cleansing of the elite over the last several months is an attempt to weaken any potential center of resistance to the course Putin ultimately chooses, giving him more room to maneuver.

The siloviki have undergone the most radical cleansing, but the cleansing process began with state-owned companies and government agencies, many of which saw their entire management replaced back in 2014-2015.

So, before the year is out we can expect to see a number of major changes — not only to staff, but also to the very structure of the presidential administration, government and political bloc, including both houses of parliament and the party system.

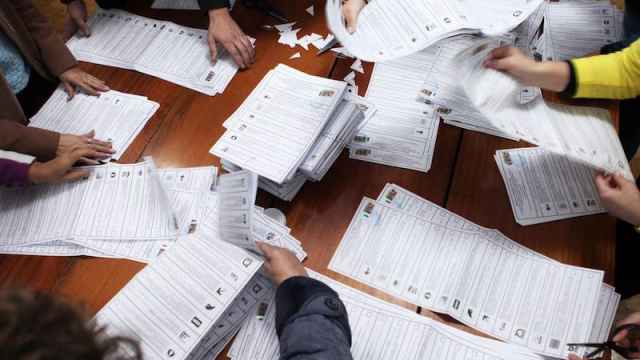

The Duma elections are over. They are no longer a restraining factor, but a stimulus to change. The election results have significantly changed the political balance not only in the regions, where new, strong, and relatively independent political figures have entered office, but also in the center. The elections have given added political weight to the Duma itself and augmented its legitimacy. In fact, against the backdrop of the impending shakeups, the Duma is looking like an island of stability.

And now no one and nothing can get in the way of the Kremlin if it wants to resurrect the Soviet Union. Especially if it seriously wants to resurrect the holy Soviet trinity of KGB-MVD-Army, as the Kommersant newspaper revealed just hours after the first election results began to trickle in.

Nikolai Petrov is a political analyst with the Higher School of Economics.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.