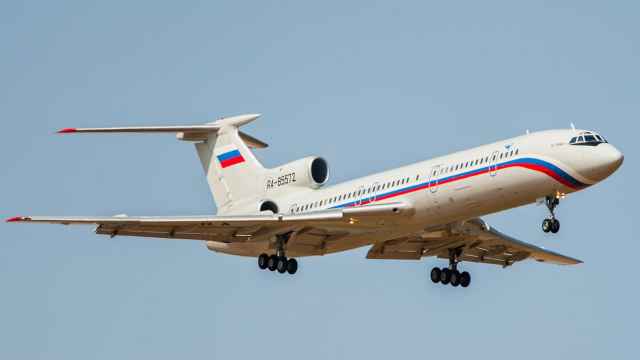

The victims of the Tu-154 airplane crash near Sochi were all civilians. They were peaceful people – performers, journalists, and even a renowned doctor. People everywhere send their condolences to the friends and loved once of the deceased. The cause of the crash is still unknown. In any case, these people are casualties of a war in which all Russians indirectly participate, whether they want to or not.

The Defense Ministry handled the flight as part of its operations in Syria. On board were members of the Alexandrov Ensemble, who were set to perform for Russian troops in Syria; journalists from three TV channels, who were to cover the event; and the doctor and philanthropist Elizaveta Glinka, who was carrying medicines for a military hospital in Latakia. The grief we feel for the victims is in no way connected with the fact that this was essentially a cultural, medical, and logistical support flight for a fighting army. Russia is at war, and civilian casualties can sometimes outnumber combat fatalities.

In fact, modern warfare most often involves non-contact fighting, and losses at the front are often low. But how do we reckon with non-combat losses in, for example, a guerrilla war with terrorists? Civilian victims of terrorist attacks can number in the hundreds and even thousands.

It is no small trick to conduct such a war, and the task of predicting the losses and costs of such a conflict is no easier. Perhaps Russian strategists made those calculations and forecasts when they decided to enter the war. But, first, no one discussed it with the public. Second, what purpose do those casualties serve?

In December alone, two Russian nurses were killed in the shelling of a military hospital in Aleppo, one Russian military advisor died from wounds sustained in the battle for Aleppo, and Andrei Karlov, Russia’s Ambassador to Turkey, was shot and killed by a terrorist.

Five Russians died in August when a helicopter was shot down as it returned to the Hmeimim Air Base from a humanitarian mission in Aleppo. Three Russians guarding a humanitarian convey were killed in May and June. In February, a Russian military advisor lost his life in Syria. And those are only the official numbers of the Russians who died in 2016. The greatest number of deaths associated with Russia’s involvement in the Syrian conflict occurred in October 2015 when a bomb allegedly planted by an Islamic State sympathizer brought down a Russian passenger plane over the Sinai Peninsula, killing all 224 people aboard.

Read more: Most Likely Causes of Black Sea Plane Crash.

“One year ago, in starting its operations in Syria, Moscow underestimated the risks of military intervention in the conflict and overestimated its own ability to secure a rapid victory,” wrote international affairs expert Vladimir Frolov in September. “As always happens in such situations, it was easier to get in that it has been to get out. But sooner or later, you have to get out of the war, and it is better to do so before the losses nullify the gains.” Those losses – and the human cost – continue to rise.

The Islamic State is a terrorist organization banned in Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.