Just a few weeks ago, Lilly Minasyan was dreaming of leaving her country for a better life in the West. In this, she was no different from other young, well-educated Armenians, who see their country’s population, economy and trust for government ebbing away.

The 26-year-old says she was convinced nothing good lay in store for Armenia. But one day in late July changed everything.

This was when she laid her eyes on a picture of a “sexy, courageous, handsome, patriotic and heroic,” who was just 22-year-old. His name was Aram Manukyan, Armenia’s newest nationalist sex symbol.

When Lilly talks of the subject of her admiration, she smiles a wide, enchanted smile. “The instant I saw his photograph on Facebook and heard his story, I fell madly in love,” she tells The Moscow Times. And was not alone. More than 15,000 people liked the same picture, most of them women.

”Neither Putin, nor [Armenian President Serzh] Sargsyan can claim to be Armenia’s sex symbols any longer,” Lilly continues.

She says she had liked Russian President Vladimir Putin when he first came to power. He was “strong, successful and sporty.” But as the years passed by, the young graduate student in political science began to wonder. “I asked myself how much more money do Putin and Sargsyan need to make before they can let other people participate in politics,” she says.

A Romantic Movement

In the early days of July, Aram Manukyan was among a group of 31 gunmen calling themselves Daredevils of Sassoun, who captured a police compound in the Erebuni district of Yerevan. Their demands were clear: President Serzh Sargsyan was to resign and release their leader, Jirayr Sefilyan, a celebrated veteran of the Karabakh war. A sharp critic of Sargsyan, Sefilyan had been arrested on June 22.

The tense situation developed into a two-week siege, complete with hostages, gun fights and violent clashes that left two policemen killed and over 60 people wounded.

It also marked the start of a romantic movement.

During the days and nights of the hostage crises in Yerevan, hundreds of people stayed out on the streets. They were not there to support hostages, policemen or even the doctors. They had come in support of the Daredevils — to support the older gunmen, celebrated heroes of the six-year long Karabakh war, and to support their younger friends and relatives, like Aram.

The protesters yelled the Daredevils’ names, artists drew their portraits, men drank to their courage, and young women fell in love. On July 22, five days into the siege, the crowd could be heard chanting: “Pavlik! Pavlik! Keep going!”

Pavlik Manukyan was the charismatic war hero, a sex symbol in his own right; and, more to the point, father of the newest Armenian hunk, Aram.

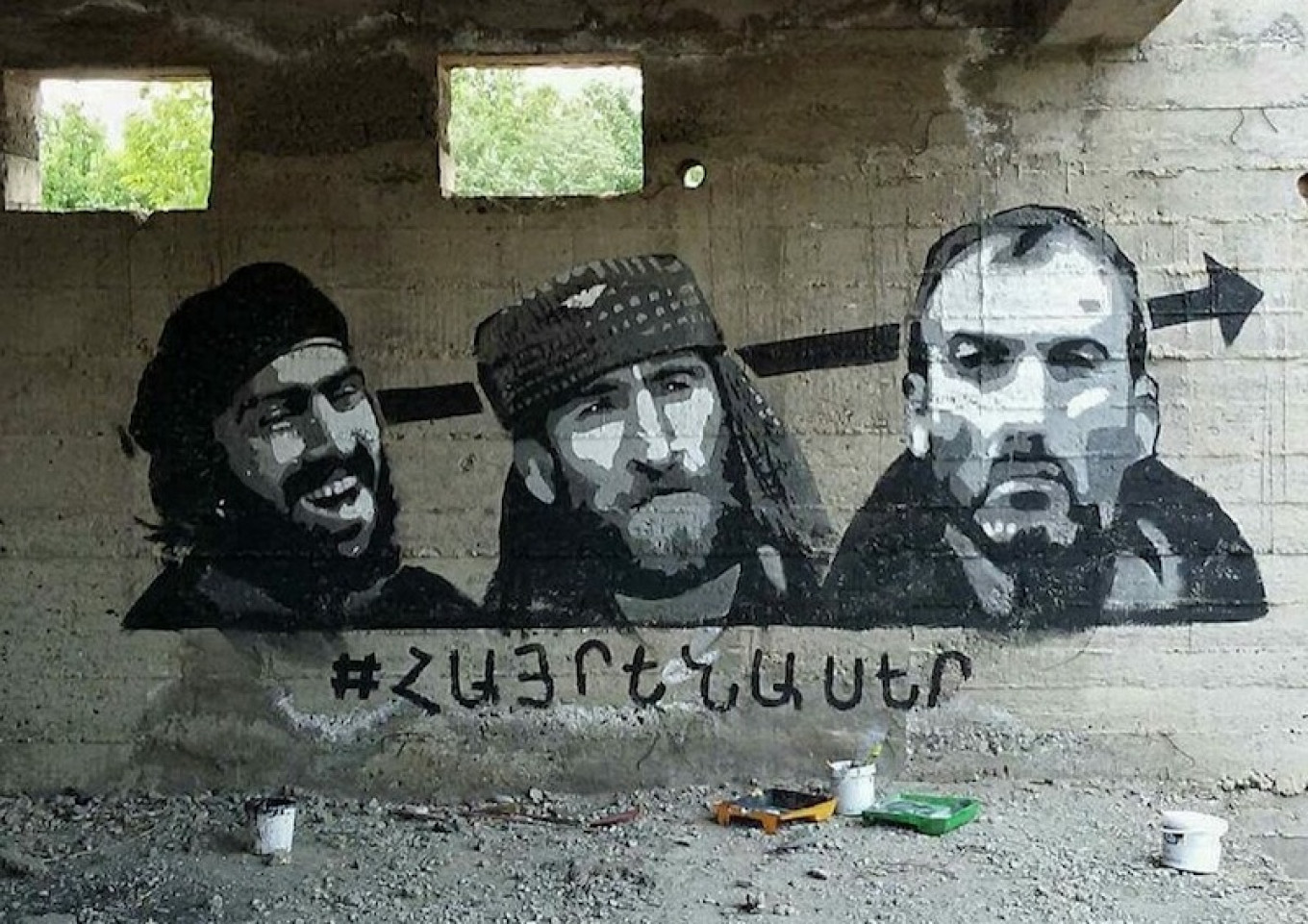

Pavlik’s fans were especially happy to hear his promises that the rebels would not cause any harm to their hostages. “We are going to fight to the end,” Pavlik said. “We’ll do everything to ensure the safety of the captives even if police storm the premises.” He was cheered when he appeared with his friend, Arabic Khandoyan, a bearded rebel in a Che Guevara beret, better known as “Lonely Wolf.”

The police enjoyed little public support. Not even the news that two of their number had been killed in the stand-off was enough to move people to their side. According to Helena Melkonyan, a manager at Ayo NGO, a Yerevan based crowd funding platform, Armenians remain angry about the brutality police showed at at last year’s Electric Yerevan protests. “They beat up people so much that nobody felt sorry for them,” she says. “I personally feel so ashamed of our police; I want to officially ask them not to protect me.”

Every afternoon, Melkonyan joined the rallies in support of the Daredevils. But before the summer, she hadn’t the slightest idea that they even existed; she was running half marathons, teaching English at a new age educational center, and reading novels by George Orwell and Haruki Murakami.

She remembers the day she found out about the Daredevils. It was July 26, 2016; a date, she says, that will always remain etched in her memory. This was the day she opened her Facebook and saw Aram’s serious, piercing eyes, staring out from under thick dark eyebrows. Like thousands of other women, the rebel moved her heart.

On the day she became obsessed, Melkonyan left a jokey post. “When I was younger, I desperately wanted to marry a policeman. I’m telling you guys, I wasn’t too bright as a child,” she wrote.

The Daredevils’ standoff gave inspiration to Armenia’s civil society. Young activists ran blogs, made statements and resolutions. “We are not Erdogan’s Turkey,” one of the activists wrote. “It’s in our cultural heritage to speak openly and we deserve it after 600 years of Ottoman oppression. Going after journalists is a sign of weakness by the government in any country.”

But on one night, July 29, Armenia did feel very much like Turkey. With cynical force, police cracked down on a demonstration of a few hundred people. Reporters were hounded, some lost their cameras and many ended up in hospital. At least 12 journalists were injured in clashes.

“They deliberately broke our cameras,” photographer Gevorg Ghazaryan told The Moscow Times on Khorinatsi Avenue. He had returned there to search for a camera part — worth thousands of dollars, a fortune in his country.

The clampdown did not only target protesters. People who had nothing to do with the rebels were also caught up in the clashes. Some of the victims included old people and children.

“Our young people romanticize the rebels, as they see real patriots and icons,” the parliament deputy Zaruhi Postanjyan told The Moscow Times. Postanjyan attended every rally last month to prevent violence. She says the government did not share such an aim. “Police threw stun grenades at the crowd, at children. It was a total disaster, ordered by a president who is terrified of losing power.”

In an interview for this article, the Bloomberg reporter Sara Khojoyan says that she was surprised at how the majority of people she interviewed during the rallies admired the gunmen and believed in Daredevils’ cause. “When the rebels eventually made a decision to surrender, people were very upset,” she says. “They somehow thought these guys could put the end to Sargsyan’s leadership.”

Today all the surrendered rebels find themselves in jail or in prison hospitals, but that does not stop their fans from keeping the spirit of their heroism up. They do so in time-honored Armenian tradition. The Daredevils themselves took their name from an epic of Armenian folklore, from poetic stories about David of Sassoun and four generations of his warriors against Arab rule.

Today the proud statue of David of Sassoun, raising his sword on a rearing horse, is a fixture of the square before Yerevan’s railway station.

Perhaps, some day, Lilly’s hero Aram will find himself similarly glorified.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.