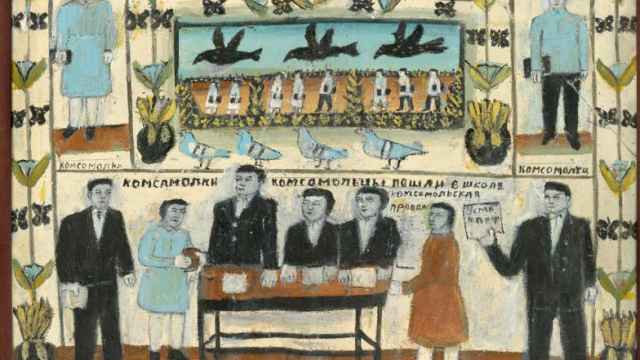

First, he disguised thousands of priceless paintings as simple luggage. Then, he loaded them onto trains and trucks assigned to a non-existent archeological expedition, which whisked them off to safety in a far flung desert town. It sounds like a plot of a Hollywood thriller, but to Igor Savitsky, it was his life’s greatest work, leading to the foundation of the Nukus Museum of Art in Uzbekistan.

That museum is regarded as one of the world’s greatest collections of Soviet avant-garde art. And now 250 of its masterpieces are on display in Moscow at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, as part of the “Treasures of Nukus” exhibition.

Officially called the State Art Museum of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, the Nukus Museum became known internationally after several exhibits abroad in the 1990s. Then in 2011, “The Desert of Forbidden Art,” an American-made documentary about Savitsky and his efforts to preserve Soviet avant-garde art, brought the Nukus Museum broad public attention.

The museum is perhaps the only tourist attraction in Nukus, the capital of the autonomous Karakalpakstan Republic in western Uzbekistan, an isolated place ravaged an environmental catastrophe caused by the evaporation of the Aral Sea.

Exhibition curator Anna Chudetskaya has been “dreaming about this exhibition for a decade.” Her first research trip to Nukus was in 2007, and she and her team spent the next three years preparing the exhibition. But the political situation at the time got in the way, and the exhibition was put on hold. “The Uzbek side just wasn’t ready for the level of cooperation we were proposing and the funding was not guaranteed,” she told The Moscow Times.

Late last year, Uzbekistan witnessed its first change of power since the fall of the USSR, following the death of President Islam Karimov, who had ruled the country for 27 years. His successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, came to Moscow for a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin last week.

“Suddenly, we were given a green light and prepared this exhibition in under two months,” says Chudetskaya. The Nukus exhibition was planned to coincide with the visit, so that the two presidents could attend it.

“We just wanted to introduce Moscow to this phenomenon,” says Chudetskaya. “Everyone has heard of Nukus, everyone knows there’s a treasure trove of art there, but no one really knows what’s exactly there, what’s left of it after the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

Savitsky was born into an aristocratic family in Kiev in 1915. His grandfather was a well-known member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. As a child, Savitsky received an excellent education, travelled abroad, and spoke fluent French. Having decided to become an artist, Savitsky entered the Surikov Institute in Moscow but couldn’t find work after graduating.

When World War II erupted, Savitsky was evacuated to Uzbekistan (he was unfit to serve due to an illness). During this period he befriended prominent Russian artists Robert Falk and Konstantin Istomin, who had also been evacuated to to the region.

This trip appears to have left quite an impression on Savitsky. When a chance to work as an artist at the Chorasmia (Khorezm) Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition came up, he took it. The expedition made significant discoveries in local history, while Savitsky developed a clear affinity for the Karakalpakstan region.

Savitsky started collecting ethnographic objects from local villages: carpets, costumes, folk art. Soon local authorities noticed his efforts and made him the head of the museum in Nukus in 1966.

The next stage was to study paintings by local artists. This led to Savitsky’s discovery of Alexander Volkov, Ural Tansykbaev, Viktor Ufimtsev and others, whose style is now dubbed “Turkestan avant-garde.”

Tansykbaev—the most famous representative of this school—was initially attracted to Fauvism and Expressionism, but later turned to Socialist Realism and became a member of the Soviet Academy of Arts. However, it was his earlier works that interested Savitsky, and these are the ones on display at the exhibition at the Pushkin Museum.

The exhibit also includes “The Bull,” a painting by the mysterious Yevgeny Lysenko. Little is known about the painter or his fate, and only a few works have survived to this day. “The Bull” has become the unofficial symbol of the Nukus Museum.

But Savitsky’s gift to the art world was not just Turkestan avant-garde. During the 1960s, the curator also started traveling to Moscow and St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) to collect paintings from his artist friends whose works had been deemed “degenerate” by the Soviet authorities. Some of these paintings he bought with the Nukus Museum’s small budget. Others he got as gifts. In some cases, he left IOUs to be paid later.

The collection in Nukus grew ever larger as it acquired “unwanted” paintings that would probably never have survived other- wise. For instance, the museum came to pos- sess about 1,200 paintings by Nikolai Tarasov, a little-known artist who was a graduate of Vkhutemas, a 1920s center of avant-garde art.

Among the items on display in Moscow are also works by Lyubov Popova, probably the best-known female artist of the Russian avant-garde, as well as more obscure painters like Alisa Poret and Boris Rybchenkov. Some of the unique finds of the Chorasmia expedition are also on view, including ossuaries and items linked with Zoroastrian (pre-Islamic Persian) religious practices.

Unfortunately, Savitsky did not live to see his collection come to global prominence: He died in 1984. Chudetskaya explains that one of the aims of the current exhibit is “to pay tribute” to Savitsky.

“What we see here,” she says, “is an individual project: the creation of a cultural center in a region that was not particularly suited for such an undertaking.””

‘The Treasures of Nukus’ runs through May 10.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.