This article was first published

KGB files from the famous Mitrokhin archive — described by the FBI as "the most complete and extensive intelligence ever received from any source" — are now open to the public for the first time. From 1972 to 1984, Major Vasily Mitrokhin was a senior archivist in the KGB's foreign intelligence archive, with unlimited access to hundreds of thousands of files from a global network of spies and intelligence-gathering operations.

At the same time, having grown disillusioned with the brutal oppression of the Soviet regime, he was taking secret handwritten notes of the material and smuggling them out of the building each evening. In 1992, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, he, his family and his archive were exfiltrated by Britain's Secret Intelligence Service.

Now, more than 20 years after his defection to Britain, Mitrokhin's files are being opened by the Churchill Archives Center, where they sit alongside the personal papers of Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher.

Professor Christopher Andrew, the only historian to date allowed access to the archive, and author of two global bestsellers with Mitrokhin, said: "There are only two places in the world where you will find material like this. One is the KBG archive — which is not open and very difficult to get into — and the other is here at Churchill College where Mitrokhin's own typescript notes are today being opened for all the world to see.

"Mitrokhin dreamed of making this material public from 1972 until his death; it is now happening in 2014. The inner workings of the KGB, its foreign intelligence operations and the foreign policy of Soviet-era Russia all lie within this extraordinary collection; the scale and nature of which gives unprecedented insight into the KGB's activities throughout much of the Cold War."

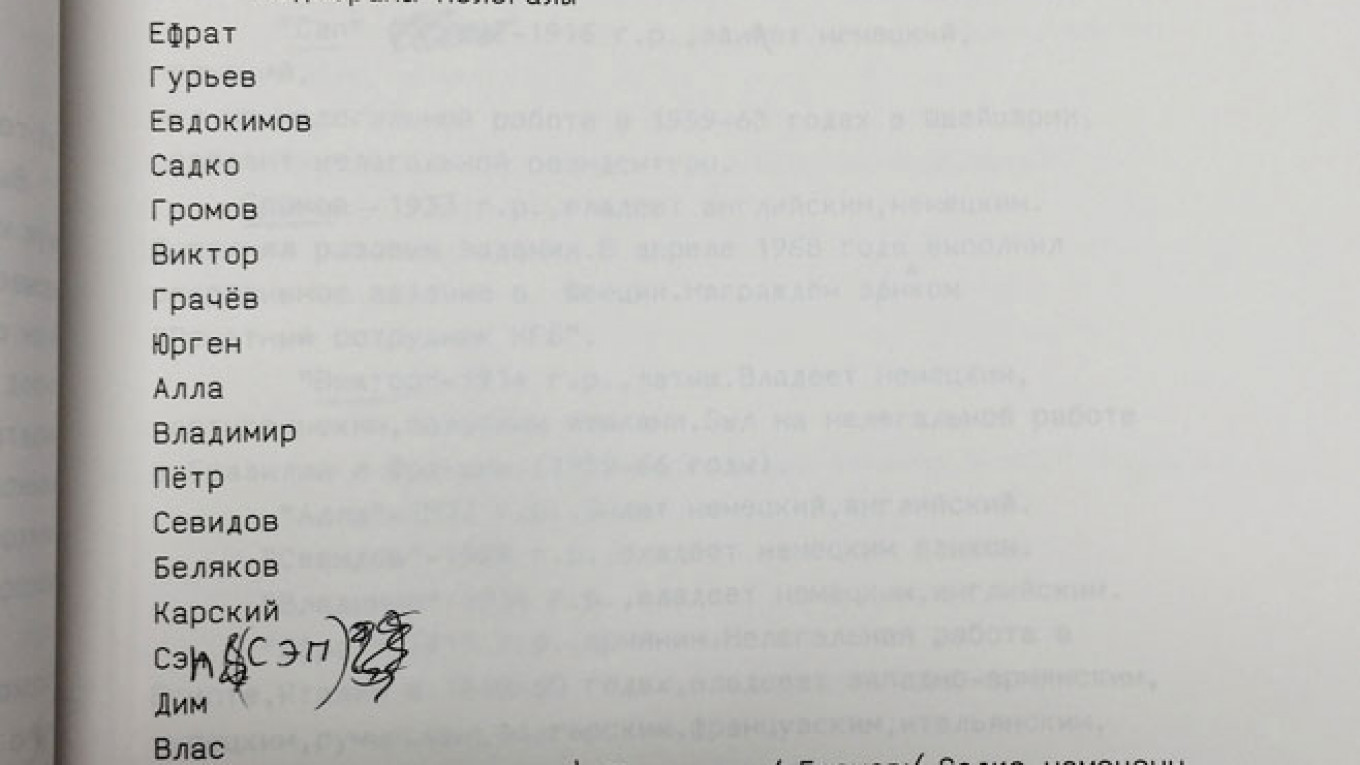

Among the 19 boxes and thousands of papers being opened are KGB notes on Pope John Paul II, whose activities in Poland were closely monitored before his election to the papacy; maps and details of secret Russian arms caches in Western Europe and the U.S.; and files on Melita Norwood, 'the spy who came in from the Co-op.'

Norwood, codename Hola, was the KGB's longest-serving British agent, who for four decades passed on classified information from her office at the British Non Ferrous Metals Research Association in Euston, North London, where nuclear and other scientific research took place.

"The Mitrokhin files range in time from the immediate aftermath of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution to the eve of the Gorbachev era," said Andrew. "Initially he smuggled his daily notes out on small scraps of paper hidden in his shoes. After a few months, he began to take them out in his jacket pockets then buried them every weekend at the family dacha in the countryside near Moscow."

"The enormous risks in compiling his secret archive might well have ended with a secret trial and a bullet in the back of the head in an execution cellar. He was a dissident willing to make the most extraordinary sacrifice."

Vasiliy Mitrokhin was born in 1922. From 1948, he worked in foreign intelligence before being assigned to the foreign intelligence archives in the KGB First Chief Directorate. From 1972 until 1982 he was in charge of the transfer of these archives from the Lubyanka in central Moscow to a new foreign intelligence HQ at Yasenevo.

Following his retirement in 1984, Mitrokhin organized much of this material geographically and, in ten volumes, typed out systematic studies of KGB operations in different parts of the world.

After his exfiltration to London, Mitrokhin continued to work on transcribing and typing his manuscript notes, producing a further 26 typed volumes, which, together with his notes, provided the basis for his publications with Professor Christopher Andrew. Vasiliy Mitrokhin died in January 2004.

Allen Packwood, Director of the Churchill Archives Center, said: "This collection is a wonderful illustration of the value of archives and the power of archivists. It was Mitrokhin's position as archivist that allowed him his unprecedented access and overview of the KGB files. It was his commitment to preserving and providing access to the truth that led him to make his copies, at huge personal risk. We are therefore proud to house his papers and to honor his wish that they should be made freely available for research."

In accordance with the deposit agreement, the Churchill Archives Center is opening Mitrokhin's edited Russian-language versions of his original notes. The original manuscript notes and notebooks will remain closed under the terms of the deposit agreement, subject to review.

This article was first published on the University of Cambridge Research website.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.