As the difficulties facing Vneshekonombank mounted, Vladimir Dmitriyev began to withdraw from work. The 62-year-old career official was unable to help the development bank he had headed for more than a decade.

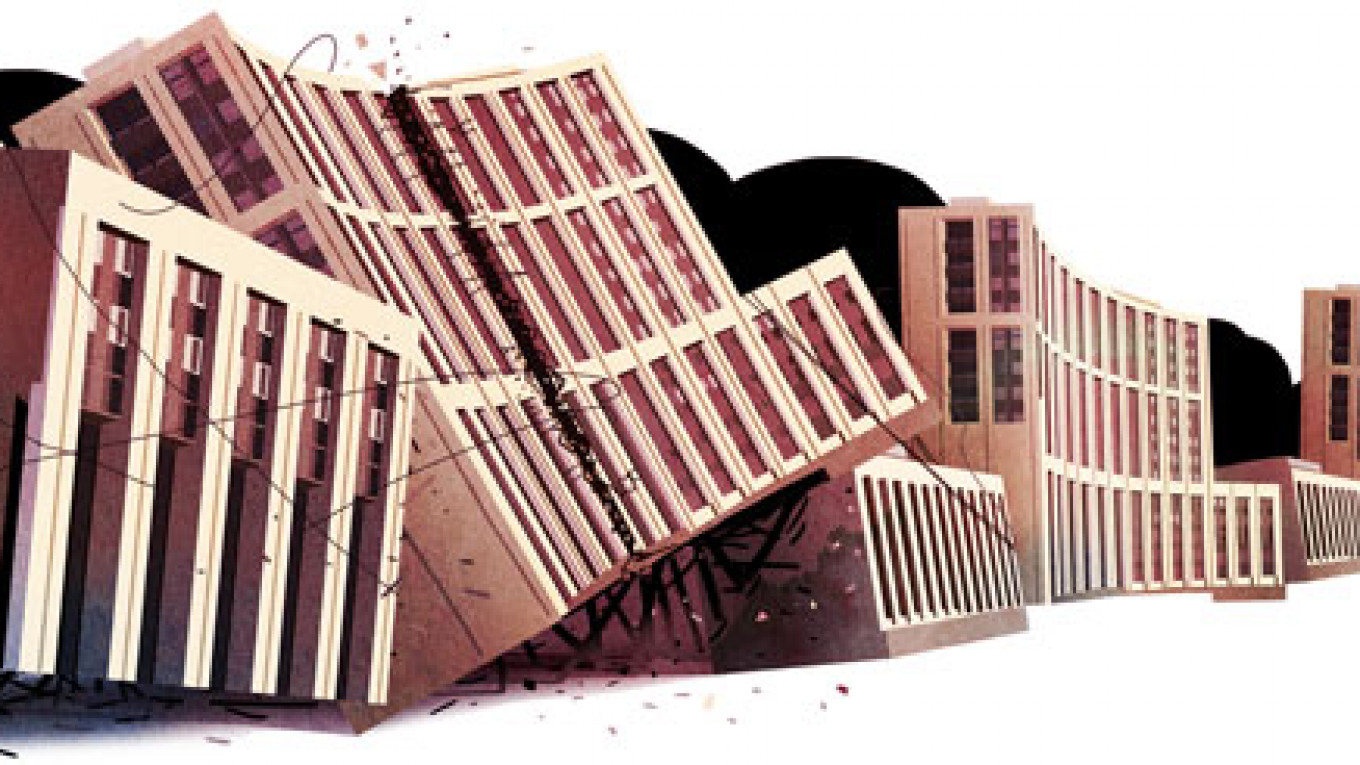

An opaque organization held firmly under the thumb of President Vladimir Putin, Vneshekonombank (VEB) was used to finance the Winter Olympics in Sochi and extend Russian financial influence in Ukraine. But Western sanctions have left it struggling to repay some $20 billion of foreign debt and in need of a huge government bailout.

Dmitriyev felt helpless, a source close to the Kremlin told The Moscow Times, as the ground moved under him. His attention wandered. On the morning of Feb. 18, he announced to staff that he was leaving. A week later, he was replaced.

State Capitalism

Vneshekonombank dates back to Vladimir Lenin, who used it to finance foreign trade in the hybrid communist-capitalist system that grew out of Russia's civil war. A century later, it became a key institution in another version of state capitalism — Vladimir Putin's.

In 2007, Putin revamped VEB into a development corporation. VEB was meant to ape German and Japanese development agencies. Regulated by bespoke legislation, its mission was to finance export and infrastructure and support innovation and small and mid-sized businesses. Almost immediately, however, that plan skidded off the rails.

When the global economic crisis swept through Russia in 2008-09, VEB became the government's rescue agency. It pumped state cash into the stock market and financial sector, rescued two struggling banks and showered loans on industrial companies.

In the chaos, VEB's original guidelines were elbowed aside. Its internal oversight and risk management evaporated, says Andrei Movchan, an economist at the Carnegie Center in Moscow. VEB quadrupled its assets to almost 2 trillion rubles ($65 billion at the time) by the end of 2009. Its corporate structure ballooned.

The crisis set the tone for politics to drive strategy. VEB lent billions of dollars to build infrastructure for the 2014 Sochi Olympics, the most expensive ever with a total price tag of some $50 billion. Meanwhile, it bought a Ukrainian bank and, in a series of secretive deals over 2009-10, lent more than $8 billion to Russian investors to buy up industrial plants in eastern Ukraine.

Secret Service Links

Throughout this period, the balding, mustachioed figure of Vladimir Dmitriyev was the face of VEB. But he was not its leader.

"It's a quasi-ministry," says Karen Vartapetov, analyst at the Standard & Poor's rating agency. VEB is overseen by a nine-member board that puts Dmitriyev together with seven government ministers and a representative of the Kremlin. "All key decisions and instructions are given by Putin and [Prime Minster Dmitry] Medvedev," says the Kremlin source.

Moreover, VEB is notoriously close to Russia's special services. Dmitriyev's own links with the spooks are unclear. He was a diplomat and served in Sweden during the late Soviet period, a time when the diplomatic service worked closely with the KGB. Others in VEB have more obvious connections. Pyotr Fradkov, a senior executive at VEB, is the son of Mikhail Fradkov, a former prime minister who is now the head of Russia's foreign intelligence service, the SVR. U.S. authorities last year arrested Yevgeny Buryakov, accusing him of using his position in VEB's New York subsidiary as cover to conduct espionage.

With Putin and the security services as backseat drivers, Dmitriyev's control over the organization was questionable. Especially since by 2009, VEB was seen as the government's financial aid dispenser. In a Facebook post, Maxim Tovkailo, a journalist at the Russian version of Forbes, recalled how an interview with Dmitriyev was interrupted by a phone call.

"What do you mean?! How did you let that happen?! Stop it immediately!" Dmitriyev shouted into the receiver, before slamming it down. Five minutes later the phone rang again, and Dmitriyev again raised his voice: "What is this!? This is our territory! Get help! There won't be any money!" In the awkward silence that followed, Dmitriyev explained to his interviewer, "It's nothing. It's just the economy minister of Chechnya has shut himself in a conference room and says he won't leave until we give him money."

Cheap Money

Foreign loans powered VEB's expansion. Overseas lenders provided money at low interest rates thanks to VEB's implicit government backing, which VEB would re-lend to its clients.

In 2014, this strategy was destroyed when Russia annexed Crimea and eastern Ukraine descended into war. VEB fell under sanctions that barred Western lenders from giving it more money. At the same time, its assets in Ukraine became useless, and a deepening Russian recession called into question whether many of the loans it had handed out would ever be returned.

VEB began to hemorrhage money. In 2014 and the first nine months of last year it lost 383 billion rubles ($5 billion) as the value of unretrievable loans and investments swelled. Even worse, VEB has around $20 billion in foreign debt that must be paid back. Officials have said around $3 billion is due for repayment this year.

Rescue Plan

As VEB's position worsened, Putin announced that Russia's development institutions had become a "dumping ground for bad loans." An increasingly beleaguered Dmitriyev became the fall guy. As rumors swirled of his dismissal, anonymous sources told newspapers that Dmitriyev had been a yes-man who had failed to inform his superiors of the financial risks they were taking.

To remedy the problems, the government turned to German Gref, a former economic development minister who now heads Russia's largest lender, Sberbank. Gref is credited with transforming Sberbank from a Soviet holdover drowning in bureaucracy into a modern, efficient bank. According to the Kremlin source, he turned down the role. On Feb. 26, Putin stripped Dmitriyev of his duties, and appointed one of Gref's deputies, Sergei Gorkov.

"Don't expect major change," said Carnegie's Movchan. 47-year-old Gorkov has worked mostly in human resources departments and is not a private sector banking heavyweight, Movchan said. More than that, Gorkov is a graduate of an academy run by Russia's security service, the FSB.

Analysts say the government cannot allow VEB to fail, since that would devastate Russia's reputation on financial markets and complicate any future borrowing. Gorkov's arrival may bring some improvements to management — he is bringing a couple of deputies, one of whom, Nikolai Tsekhomsky, has long experience in the private banking sector. Gref will also take up an unofficial oversight role, according to the Kremlin source. VEB did not respond to a request to comment.

There may even be a purge of VEB's less scrupulous managers, many of whom are rumored to have grown rich. One former VEB executive, Ilgiz Valitov, was arrested shortly after Gorkov's appointment, though it is unclear whether the move relates to his time at VEB.

The core of any rescue plan, analysts say, will be to sell non-core assets — many of them at a loss — and have the government give VEB enough money to survive.

That is likely to mean a loan of at least 150 billion rubles ($2 billion) this year, at a time when the government is short of money and the economy is in recession. Estimates of the total aid needed go as high as $1.5 trillion rubles ($20 billion), spread out over several years — equivalent to about 2 percent of Russia's gross domestic product.

Mopping up VEB's legacy will be slow and painful. It is a predictable outcome, says S&P's Vartapetov: "VEB became an off-budget fund through which the government funded its budget expenses, simply putting off those costs."

Those costs are now due, and the government is paying the bill.

Contact the author at [email protected]. Follow the author on Twitter at @peterhobson15

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.