How do you begin explaining a revolution to children? In the early days of the Soviet Union, this is exactly what a group of artists tried to do. By the time their efforts were curtailed in the mid-1930s, the cohort had produced an impressive body of futuristic avant-garde illustrations and poems — all of which fundamentally changed the Russian approach to children.

A century later, and a tiny Moscow gallery opened a new exhibition dedicated to their work.

Before you even reach the “Constructivism for Children” exhibition, you take a step back into 1920s Soviet Moscow. The gallery is not easy to find, nestled in among the residential backstreets of Moscow’s Shabolovka neighborhood. These streets are home to much of the city’s avant-garde architecture.

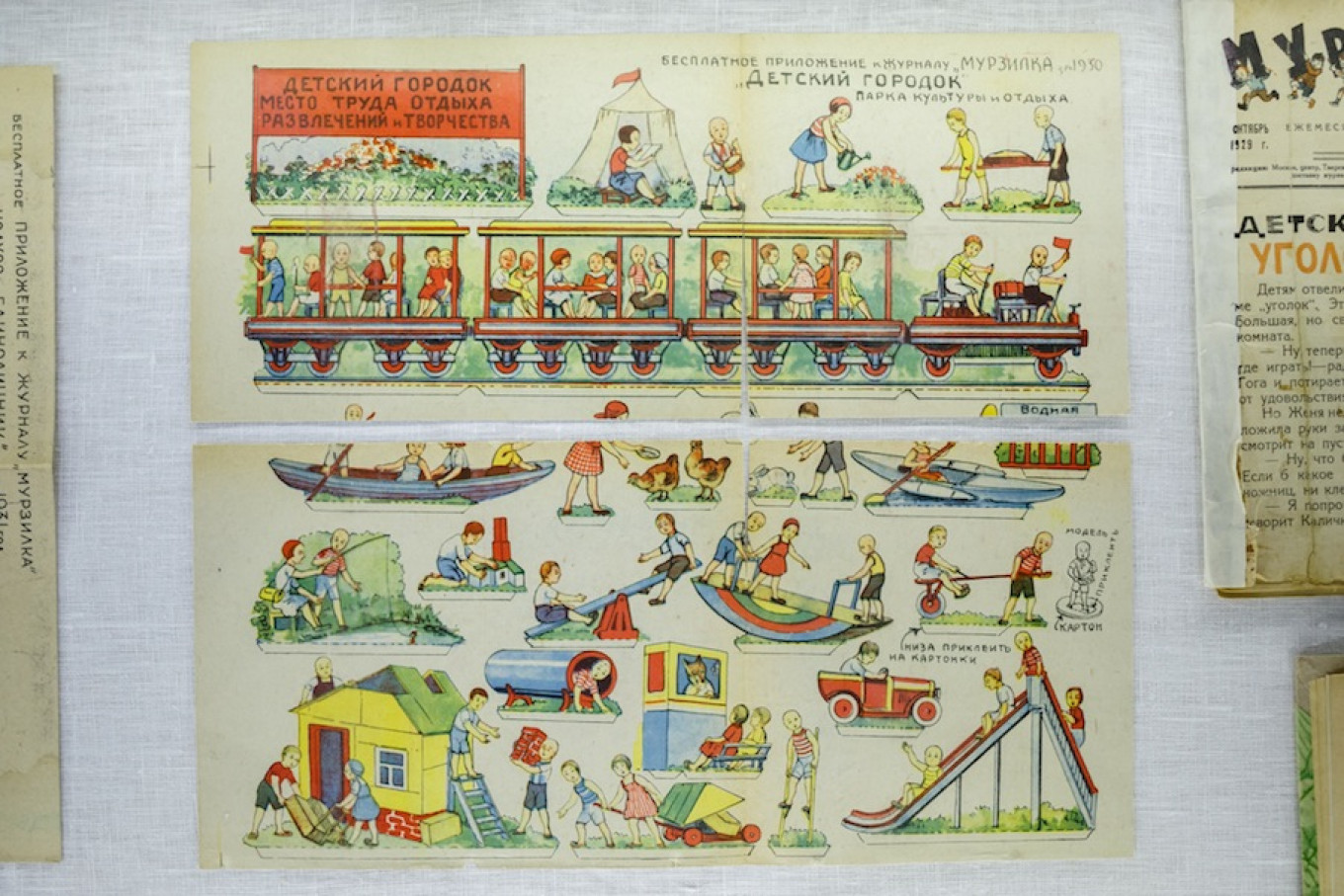

The gallery itself is housed on the ground floor of a 1927 housing complex. The exhibition’s three small rooms are filled with children’s books’ illustrations taken from the Russian State Children’s Library and private collections.

“I wanted to show a relatively narrow range of books that were published after the revolution to teach children about their new surroundings,” says curator and avant-garde expert Alexandra Selivanova.

Grown-Up Books

Before the grey days of Stalin’s 1930s, early Soviet children’s literature was humourous, exotically illustrated and far less controlled by state censors than adult literature. “It was freer and more flexible,” says Selivanova.

Through children’s books, writers found a more direct way of communicating with the public. This meant that, for the first time, serious poets like Osip Mandelstam and painters like Vladimir Lebedev started writing and drawing for children.

Millions of these books were printed and distributed across the Soviet Union, in far larger quantities and with far freer content than adult novels. “It was a secret revolution,” says Selivanova.

Whereas pre-revolutionary Russian children’s literature focused on romantic fairy tales and toys, the 1920s brought a new era of explainer books. The subjects became more complicated: stories were written about factories, gold mines and oil refineries. For the first time, Selivanova says, children were treated as “little human beings” who, if taught properly, could be able to make anything.

As a result, children’s books were written not only by writers and poets but by people who were industrialists by profession.

One of those was Boris Zhitkov. A ship designer who started writing about his travels for the children’s magazine Ezh (“Hedgehog”), which existed between 1928 and 1935. Another was Mikhail Ilyin, a chemist who wrote “One hundred Thousand Whys,” explaining things like why potatoes are dry after you boil them in water. His books were illustrated by Nikolay Lapshin, who drew complicated plans in black and white.

“This was scientific text and the subjects were boring, but they made it fascinating,” says Selivanova.

A significant part of the exhibition is dedicated to books that introduced children to urban life. As the Soviets proclaimed ambitious Five-Year-Plans to catch-up with the industrialization of the West, thousands of Russians migrated from rural areas which barely had dirt roads into towns and cities. “It was a completely different life for millions of village children,” says Selivanova. Some of them had never seen public transportation before. In 1926, Mandelstam wrote “The Two Trams,” — a poem about two trams called Klik and Kram, who are actually brothers, riding around the city looking for each other.

An Unsung Hero

Selivanova’s exhibition also honours a forgotten Russian pioneer of children’s literature and juvenile rights. In the 1920s and 30s, Yakov Meksin collected over 60,000 children’s books published in the Soviet Union. He even traveled the world showcasing his collection, including to Western Europe and Japan. In 1934, he founded the Soviet Union’s first Museum of Children’s Books in Moscow, in which children were taught how to print their own stories.

“This was probably the first interactive museum in Russia,” says Selivanova, who organizes workshops as part of the exhibition in memory of Meksin’s “laboratories” for children.

The golden age for Soviet storytellers came to an abrupt end in 1937, the beginning of Stalin’s Great Purges. Meksin’s museum was shut down and he was sent to a Siberian gulag, where he died in 1943. His collection was confiscated and scattered around the Soviet Union, and his name was largely forgotten by history.

Still, the legacy of the books lives on. Millions of these are hidden in households all over Russia for children to read.

“I hope they can make a comeback,” says Selivanova.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.