There’s a knock on the door. “‘Hello! I’m a foreign agent. Can I ask you a question?” the person on the other end says.

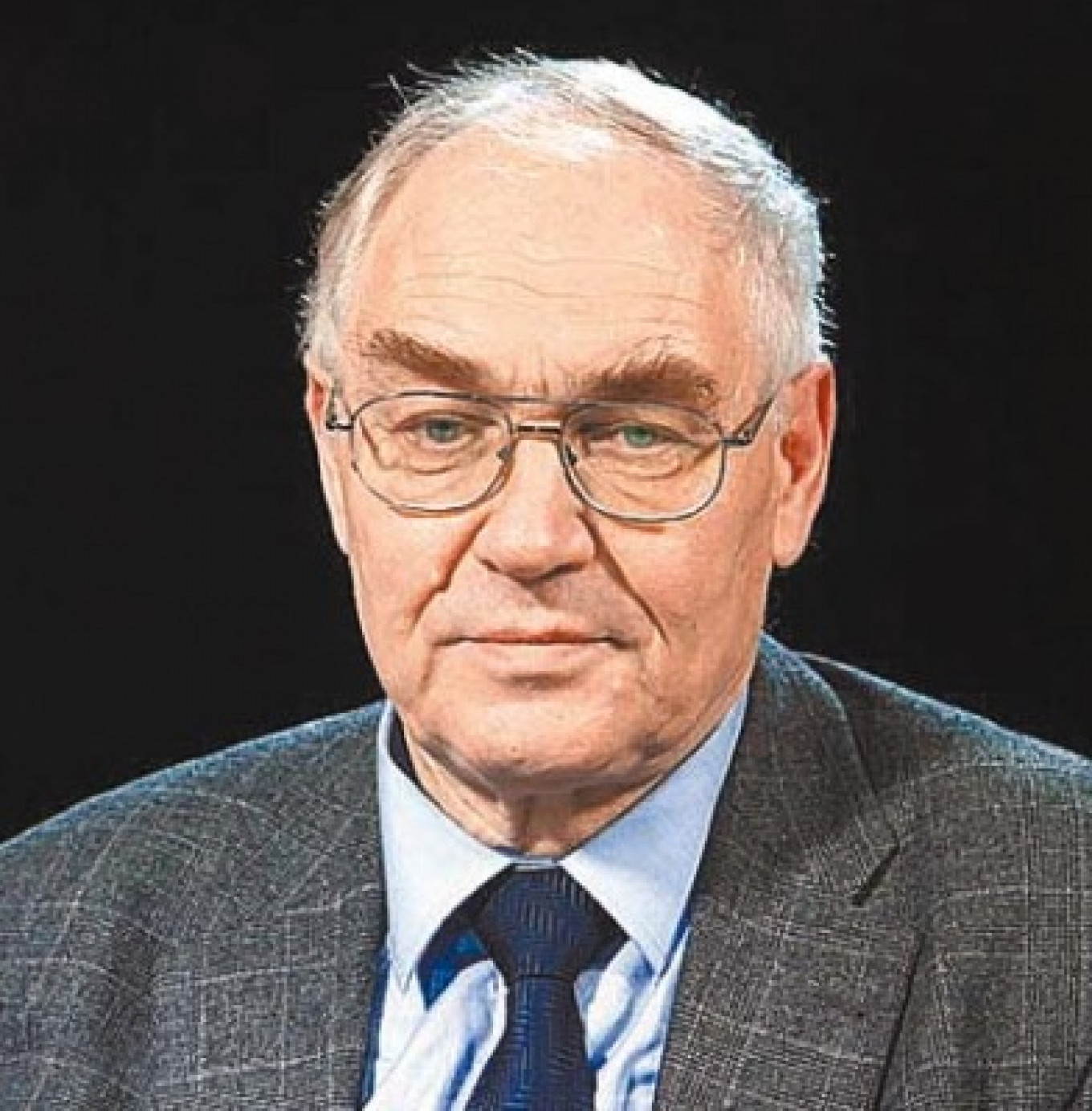

Six months ago, Lev Gudkov could still smile during an interview with The Moscow Times at the thought of the average Russian’s reaction to such an introduction from a pollster at his door.

Since then the mood at the independent Levada Center has soured. On Sept. 5, the Justice Ministry included Levada on its “foreign agents” registry after finding the NGO was engaged in “political activity” and receiving funding from abroad. It came on the doorstep of a parliamentary vote and right after Levada published an 8-percent drop in ruling party’s United Russia’s rating.

The decision was a long time coming. The pollster first received a warning from prosecutors in 2013. Still, its current predicament is “a trial” and has an air of finality, says Natalya Zorkaya, head of sociopolitical research at the Levada Center, the strain visible on her face during a meeting at its headquarters in central Moscow.

In the short term, the Levada Center will have to identify itself in surveys and publications as a “foreign agent,” a Soviet-era term with connotations of espionage. In the long term, the pollster says, it will likely be forced to halt its work completely as it struggles with government audits, an absence of funding and stigma.

The Levada Center can contest the label in court, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov hastened to tell media. But the pollster’s troubles are a telling reflection of the change in atmosphere since its inception.

Ask Gudkov, who has run the pollster since Levada’s death in 2006, about the perestroika period and his eyes begin to twinkle.

As Russians began to question their government and their predicament under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev in the late 1980s, a group of pollsters led by Yury Levada, the godfather of Russian sociology, began to question them as well.

“There had been no interest in opinion polling before,” says Gudkov. “‘Why would you study what people watch? They watch what we show them!’ That was the attitude in Soviet times,” he says, in a reference to Sergei Lapin, chairman of the Soviet committee for television and radio.

When in 1989, the sociologists at the All-Russian Public Opinion Center (VTsIOM) including Levada and Gudkov, asked citizens to respond to a long list of questions, they expected several hundred replies at most. Instead, employees at the local post office could barely move among the stacks of the roughly 200,000 letters they received. “It was the first time people were asked what they thought, so they approached it like a referendum,” says Gudkov.

Ironically, the Levada Center was born out of a standoff with the very regime that is now pushing it toward closure. When Vladimir Putin came to power, Yury Levada’s team continued to document public opinion on sensitive topics, such as the wars in the republic of Chechnya — credited with allowing Putin to strengthen his hold over the country in his early days in the Kremlin — and support for United Russia.

For the Kremlin, the lack of control over potentially opinion-shaping research was worrying. A staff reshuffle at VTsIOM followed in 2003, with the Kremlin looking to appoint more pliable board members. Levada resented the interference and set up his own private pollster, which since then has grown into the most authoritative voice on Russian public opinion.

Given the lack of other feedback mechanisms, such as fair elections and the possibility of protesting without repercussions, some argue Levada Center polls are the only reliable mechanism to gauge what Russians are really thinking.

While its results mostly coincide with those of the two major state-run pollsters, the All-Russian Public Opinion Foundation (FOM) and VTsIOM, “we don’t have a monthly get-together with the Kremlin,” says Gudkov.

Levada has many enemies, however — and they don’t just reside in the Kremlin.

For years, it has published figures showing widespread support for Putin, including his famous sky-high approval rating and many of his most controversial policies. A study in 2015, for example, showed most Russians thought gay people should be “liquidated” or “ostracized” from society — not exactly the answer progressives are hoping for.

According to Gudkov, some of the Levada’s harshest critics are the liberal opposition who argue the numbers are skewed.

“They don’t want to accept that a large mass of people, poor and provincial, support an authoritative regime,” he says. “But it means they’re effectively saying: I only rely on polls that agree with my point of view.”

“It’s exactly what our respondents [who support Putin] say, too,” he adds.

In the current political atmosphere of antagonism between those who support the Kremlin and those who oppose it, “Sociology has become the main object of suspicion: in the press, at seminars, by politicians,” he says.

For Gudkov, it’s not about the numbers, but about their interpretation. His polls have steadfastly shown overwhelming support for Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, for example. “In focus groups, respondents say: ‘We showed the world our teeth, we finally started respecting ourselves,’” he explains. “These people are poor, they suffered hugely after the fall of the Soviet Union. All of Putin’s demagoguery plays into this.”

It is interpretations such as these that have made the Justice Ministry classify Levada’s work as “political activity,” at the request of the ultrapatriotic anti-Maidan movement.

In a report published online, the ministry cited several of Gudkov’s statements, including one made in a lecture in July 2016 in which he described Russia as “a closed authoritarian system, where the state leans on law enforcement, special forces, oligarchs, state officials and bureaucracy and represents their interests.”

The pollster has had support from unexpected corners. Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov has called its blacklisting “complete nonsense.” The Russian Association for Market and Opinion Research (OIROM) also published a letter contesting the classification of sociological research as “political.”

“Data from sociological research only reflects objectively existing societal-political views and the beliefs of the country’s citizens, but doesn’t shape them,” it said in an online letter, asking the Justice Ministry to review its decision. The letter was also signed by VTsIOM and FOM.

But the support is ambiguous. “Insofar as we are colleagues in the same profession of collecting and presenting data, I feel solidarity,” says Alexander Oslon, head of FOM. “But it’s not our job to be political publicists. There are people who make boots [pollsters], people who wear them [consumers] and analysts who decide when you can wear them,” he adds.

Even if Levada dials down its tone, its future looks gloomy. Already, some regional authorities have stopped working with the pollster, Gudkov says. And after such publicity the stigma of the “foreign agent” label will be difficult to shake, making respondents wary of answering truthfully or answering at all.

Meanwhile, the pollster will be forced to sever ties with all foreign partners, including educational institutions, such as the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which, because it received funding from the Pentagon was classified by the Justice Ministry as representing the interests of a foreign government.

“We’re caught in a trap,” says Zorkaya. Meanwhile, having polled Russians for decades, she expects Levada’s troubles will largely go unnoticed.

“Most Russians will have no idea this happened,” she says. “But among those who do, a majority will support it or feel completely indifferent.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.