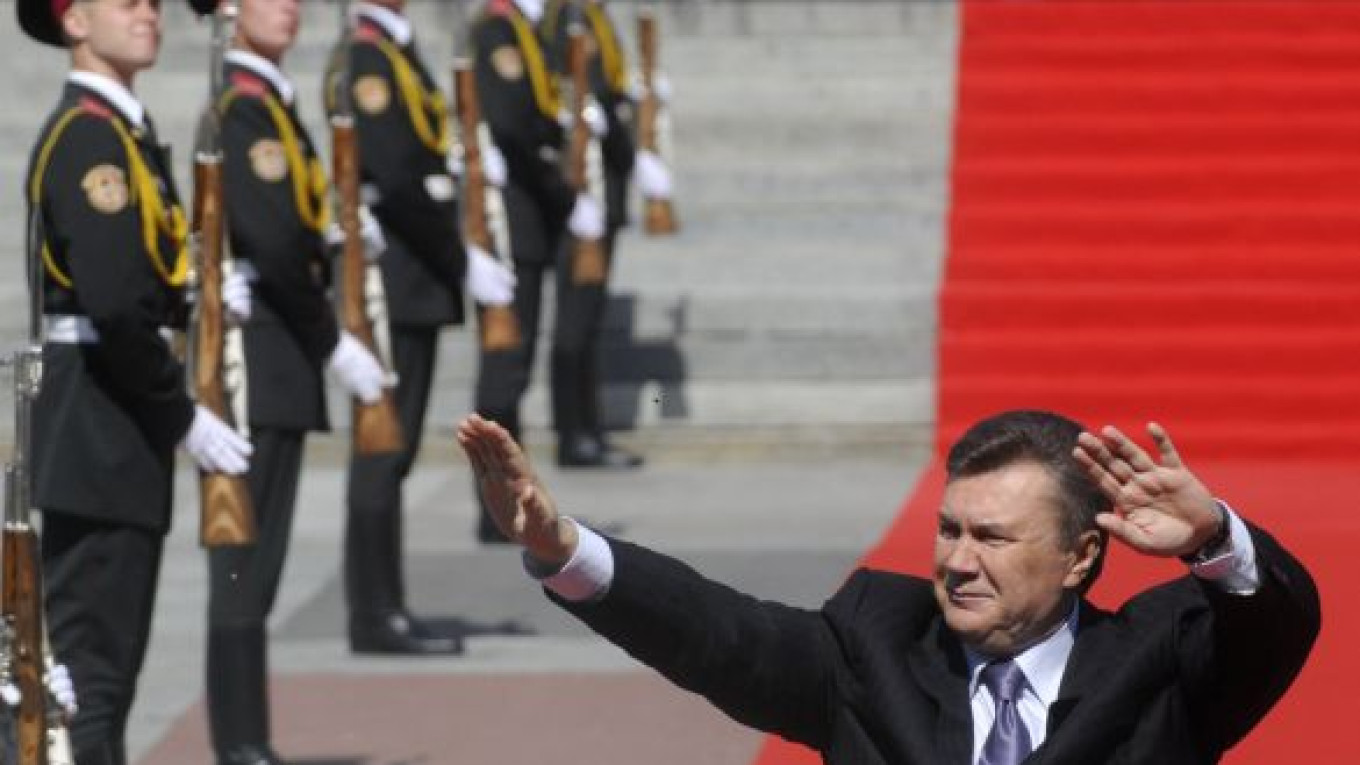

KIEV — The speed with which Viktor Yanukovych has consolidated his power, stitched up a strategic deal with Russia and ended Ukraine's long romance with NATO has taken his opponents and many in the West by surprise.

But although he has coasted through his first days in office with remarkable ease, the president is far from proving he can breathe life into the shattered Ukrainian economy, critics say.

Just as Yanukovych chalked up his 100-day milestone last week, breezily promising prosperity and the growth of a competitive economy, the International Monetary Fund weighed in with a reality check.

Unconvinced by the government's budget revenue figures, it said it would send a fresh mission to Kiev this week. The IMF wants to check the books again before it considers giving the nod to a new, multibillion-dollar bailout, regarded as vital for the country's economic recovery.

An influential Ukrainian weekly, Dzerkalo Tyzhdnya, pulled no punches. Yanukovych's five-year economic program, it said, was an evasively worded product of "tunnel vision" that offered no reforms for an economy ridden by corruption, malpractice and protectionism — and which shrank by 15 percent in 2009.

"The president and his team came to power naked and barefoot as far as understanding what new direction to take for the country and how to implement it," an editorial said.

Even Yanukovych's critics acknowledge, though, that since taking office in February he has acted with remarkable speed to end the political paralysis of the previous administration.

A pro-Yanukovych majority dominates the parliament. He has installed allies in key administrative regions and in the top echelons of the military, intelligence and diplomatic services.

The Orange Revolution opposition is in disarray, with his old rival, former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, finding it hard to establish acceptance as its natural leader.

Crucially for Yanukovych, he has kept on side with the big business lobby in Ukraine and specifically with powerful wealthy backers, like steel magnate Rinat Akhmetov, who bankrolled his campaign.

After a deal with Russia in April to secure cheaper gas in exchange for letting it keep its navy in a Ukrainian port until 2042, Yanukovych gave another gift to Moscow by finally unhitching Ukraine from pursuit of NATO membership.

Reversing a 2003 policy goal that was ardently taken up by his pro-Western predecessor, Viktor Yushchenko, Yanukovych declared that NATO membership was off the agenda.

Ukraine will pursue a "nonbloc" course while keeping integration into the European mainstream a top priority, he said.

His sharpest critics — Tymoshenko in the lead — say Yanukovych is gambling recklessly with the national interest in his dealings with Russia, on which Ukraine relies heavily for energy imports.

Others say his advisers, representing Akhmetov and others, cannily know where to draw the line, and Yanukovych has indeed prudently stepped back from taking Russia's line in some sensitive issues.

On language rights, for example, he has rejected some pressure from Moscow to make Russian a state language in Ukraine and, while a mother-tongue Russian speaker himself, doggedly delivers public speeches in Ukrainian.

And, even though he has ditched pursuit of NATO membership, the parliament has given the go-ahead to Ukrainian participation in NATO-led naval exercises in the Black Sea.

But Moscow — apparently sensing a historic opportunity — seems to be pressing for greater strategic penetration into Ukrainian markets for Russian business.

A proposal by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin for a merger between Gazprom and Ukraine's crisis-ridden state holding Naftogaz Ukrainy has been coolly received by the Yanukovych camp, although it remains on the table.

"With breathtaking naivety, he assumed that if Ukraine gave Russia everything it reasonably could ask for, the pressure would stop," said James Sherr, head of the Russian and Eurasian program at the London-based Chatham House.

"Instead, Russian pressure has intensified. We see this with the Naftogaz-Gazprom merger proposal. We see it with demands to acquire more and more assets in Ukraine's energy system and the pressure on the gas transit system," he said in an interview with the Kyiv Post.

Meanwhile, Yanukovych has failed to make his mark with the European Union — even though he has assured Brussels that his priority is for Ukraine to join the bloc one day, Sherr argued.

As things stand now, Ukraine's sick economy hardly qualifies it for EU membership. Yanukovych's critics say there is no sign that things are about to change soon.

Ukraine's liberal intelligentsia, too, is alarmed at what it sees as growing authoritarianism in Yanukovych's leadership.

Its mass media, which gained huge freedoms under Yushchenko's rule, is complaining increasingly of pressure — mainly from their own oligarch owners who back Yanukovych.

Referring to the danger of "creeping authoritarianism," political commentator Vladimir Fesenko said: "We may very soon arrive at a Ukrainian model of managed democracy."

"Yanukovych in his 100 days has built a clearly coordinated system, but this system will not serve the people," Yanukovych's old enemy, Tymoshenko, told a news conference. "It will be a country not for the people and not one that has a clear pro-Europe perspective."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.