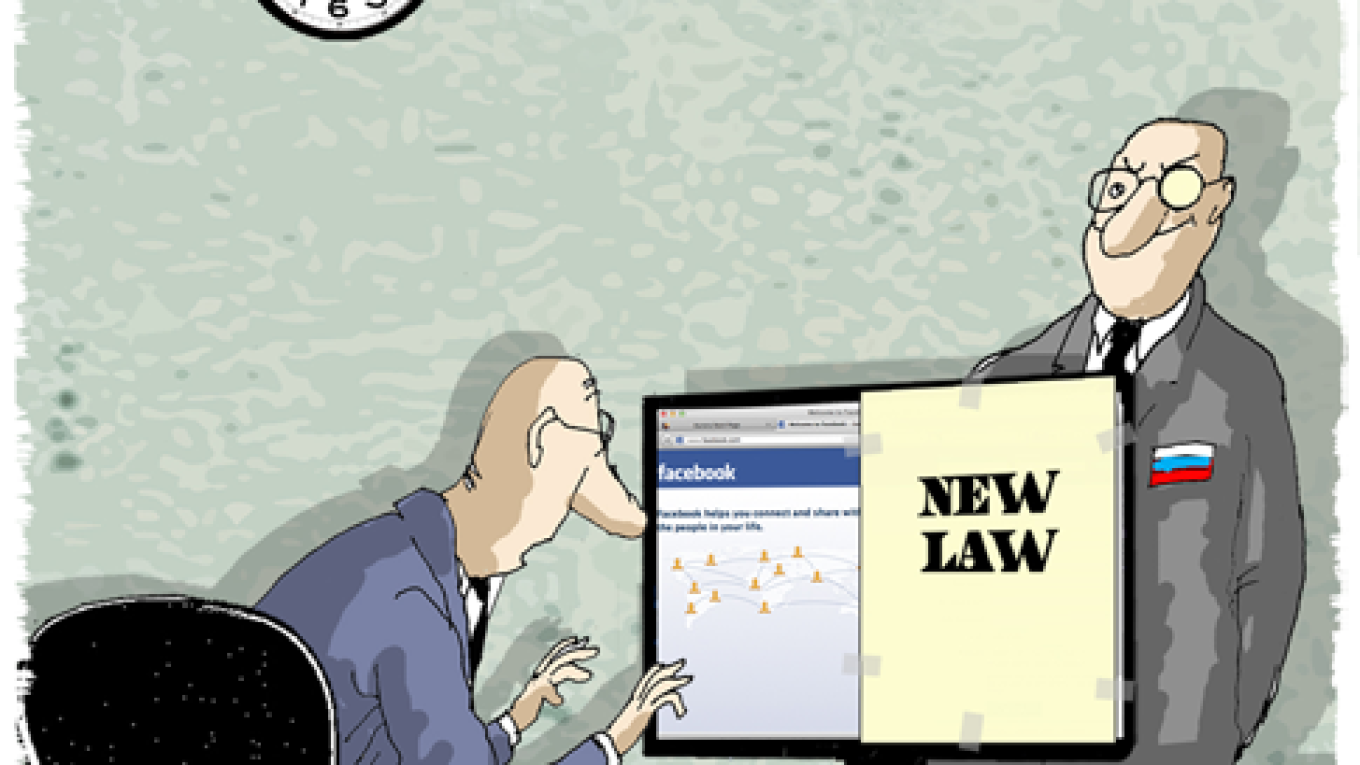

Last year, approximately 20 countries adopted laws requiring the localization of the processing of their citizens' personal data. A similar law went into effect in Russia on Sept. 1. As that date approached, everyone wondered if it would mark the start of a new Iron Curtain. That law was passed back when the price of oil exceeded $100 per barrel, the ruble exchange rate stood no higher than 34 to the dollar and the authorities had great confidence in their actions.

Now everything has changed. Russia no longer speaks from a position of economic strength. Is it wise to exacerbate the current unenviable economic situation by introducing new restrictive measures?

No less than half of all Internet companies working in Russia have expressed their unwillingness to comply with the new law, and no doubt many more are simply holding their tongues. Such giants as Apple, Google and Facebook generally do not, in principle, localize their data.

With relations between Moscow and the West continuing to worsen and the value of the ruble plummeting, the Russian market is becoming less attractive for those companies. Russia is no China in terms of sales volumes. If the Russian authorities want to actually help those Western forces interested in isolating and marginalizing this country, then they are on the right path. Enforcing the letter of this new law would isolate the Russian Internet, or whatever remains of it.

The Communications and Press Ministry and communications watchdog Roskomnadzor have said little about how they would enforce the vaguely worded law, effectively giving freedom to officials to interpret it as they please. No doubt senior Kremlin officials will follow political considerations to set policy — concerning, for example, whether to prohibit Google and Facebook from operating in Russia — and hand down their decisions to the supervisory agencies ostensibly entrusted with that task.

Roskomnadzor head Alexander Zharov indicated that no punitive actions would happen quickly, but might result from planned or snap inspections, or from orders from above. Roskomnadzor has an undisclosed list of 317 companies that it will inspect for compliance with the law and possibly get banned from working in Russia.

The law does not apply to sites providing airline tickets, visas and a number of other services such as hotel reservations through Booking.com — a company that the authorities say has complied with the requirement to localize its data. However, "non-localized" Internet stores such as instant messaging services and many others do fall under the law.

The Communications and Press Ministry has unofficially explained that the law does not apply to all Internet sites operating in Russia, but only to particular types. The criteria include sites using domain names connected with Russia or one of its constituent territories and/or the presence of a Russian-language version of the site.

The authorities can also take into account "at least one of the following": the possibility of making payment through the site in rubles, the ability to conclude a contract for the delivery of goods, the provision of services or the use of digital content on Russian territory, the use of Russian-language advertising, or other circumstances (a favorite proviso of the Russian authorities) "clearly indicating that the owner of the Internet site intends to include the Russian market in its business strategy."

That wording enables the authorities to either strictly enforce the letter of the law or else take a more lax approach, depending on circumstances. What's more, the Communications and Press Ministry and Roskomnadzor sometimes interpret the law differently — for example, concerning the personal data of employees of foreign firms. That only makes enforcement of the law even more fun for all involved.

Many experts point out that the attempt by some countries to "protect" personal data has placed an unnecessary strain on their economies, and that rigidly enforced localization has a negative effect on any business connected in some way with the Internet.

But that is not the main problem. In fact, nobody has yet proven that such measures are effective in protecting personal data. Does localization protect against personal data "leaking" abroad? Not at all. Even the new Russian law accepts as inevitable the creation of "proxy" databases and the likelihood that foreign companies will process the personal data of Russian citizens in other countries.

Forcing information into centralized data centers might make it easier for Russia's intelligence agencies to hunt for enemies of the regime, but it also makes it more vulnerable to foreign hackers. Just recall the dozens of attacks Chinese hackers waged against databases in the United States.

The people who drafted the Russian law do not understand how modern information systems work and attempt to impose a "Middle Ages" approach to regulating data in the 21st century. Enforcing the law will not only fail to protect personal data and waste precious money and resources, but it will also deepen Russia's isolation by excluding it from the global information network and destroying the little interest investors still have in this country.

Those lawmakers fail to understand how experts analyze not so much personal data as so-called metadata. That is not the tracking of individual phone conversations — which are difficult to digitize and process — but the metadata of all calls collectively: the time, place, duration, frequency of calls to this or that individual, the analysis of clusters of callers and so on. That information is easily obtained, but no lawmakers in Russia — or in any other country — consider such metadata as "personal data."

The question of the localization of data in European countries remains a marketing and PR issue. Companies fight for market share and customer confidence by "anteing up" to create localized data centers. With horror stories of the damage wrought by former NSA leaker Edward Snowden still fresh, politicians like to remind voters that they are concerned about protecting personal data.

There are economic reasons behind the desire to pressure Internet companies into moving data centers onto the territory of other countries: it creates jobs and stronger ties with those national markets. However, that is accomplished not through brute force and threats, but through dialogue. With positive incentives, Internet companies will generally agree to incur the expense of setting up data centers in other countries, but that has absolutely nothing to do with protecting personal data.

And such a dialogue only makes sense if a company has so much interest in a national market that it is willing to go along with the charade of "protecting personal data" by shouldering the expense of creating localized data centers.

But if the market is not large, there is no reason for the company to spend the money. As for the Russian market, it is probably more dependent on whether the owners of modern information technologies will agree to work here, or bypass it and doom the country to backwardness and stagnation.

The West also feels it is pointless to cater to the whims of authoritarian leaders and regimes that eventually pull some stunt which makes meaningful cooperation impossible. And if the country has a small market, the motivation to make concessions decreases accordingly.

Soviet leaders told their people: "Why would you want to live beyond the Iron Curtain? Life is worse over there." Will today's Russian leaders fall into the same trap?

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.