Two very important nongovernmental organizations in Russia were compelled to close their doors last week — the Dynasty Foundation that funded the publication of scholarly literature and research programs for young high school graduates, and the Committee Against Torture that fought against police abuse. Protest rallies by several hundred Dynasty supporters aside, the demise of the two prominent NGOs went practically unnoticed in Russia. That means Russian society as a whole does not care if its leading scholars and scientists have a way to publish their research and discoveries and that nobody has the power to prevent abuses and torture by the police.

This situation has only deepened the now-familiar split in society. A small minority of Russians is almost nauseous at this type of behavior by the authorities, while the vast majority can summon no more sense of conscience than to say, "Why get all worked up over some NGO or other? It's summer — it's time for vacation!" Some even add the sacramental comment: "The main thing is that Crimea is ours again!" And there are even a few who swallow the relentless propaganda on state-controlled television so completely that they turn with a hint of suspicion to those upset over the death of Dynasty and ask: "Why are you so worried about Dynasty, a 'foreign agent' organization? Perhaps you are an enemy sympathizer yourself."

That same division comes to the fore every single day, and it leaves people either praying for the president's success or for his early departure. Russians are divided over every successive controversy: How should they react to a prominent actor's politically incorrect comments regarding a neighboring country? Is it right to air coverage all day long of an exchange of artillery fire in the Ukrainian city of Mukachevo when Russian paratroopers were killed when their barracks collapsed on them in Omsk?

Each successive conflict further differentiates the critical minority from the pro-Kremlin majority. That majority does not take much interest in the minority, but intuitively senses where to draw the line. In fact, the minority and majority do not belong to the same community, although as yet nobody admits that publicly.

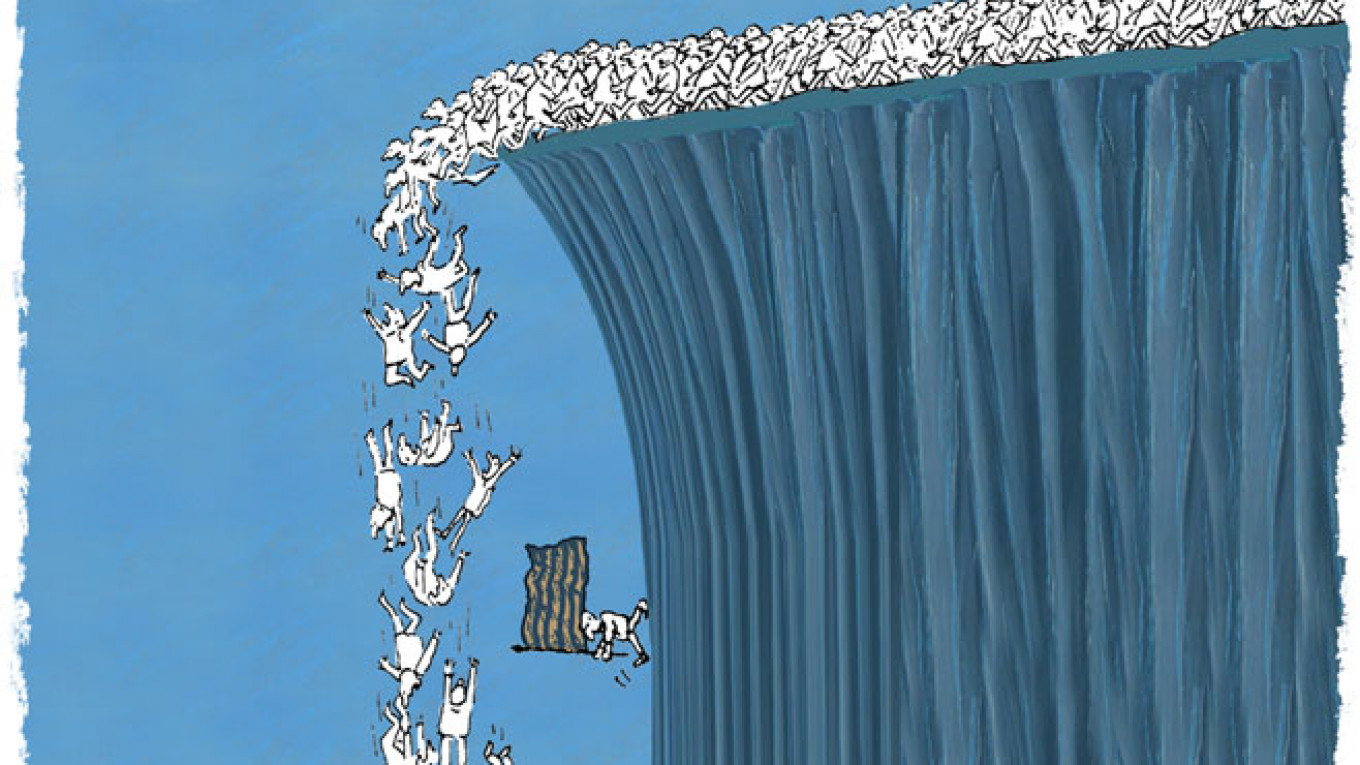

And the fact that Dynasty's closure went virtually unnoticed by the Russian minority indicates that something is wrong with this country's civil society. After all, if Russia's civil society was alive and well, the obvious injustice and absurd charges that led to Dynasty's demise would have elicited a storm of civil protest. The absence of such widespread protest means that civil society has been reduced to ordinary living room conversations about all the horrible people and governments in the world and what it will probably take before Russia finally parts ways with that backward and degenerate company forever.

But, of course, it is not that simple. Anyone who believes that the rest of the world has gone crazy might consider consulting a psychologist himself.

Looking at the situation more dispassionately, it becomes clear that it is pointless to look for a civil society in Russia that genuinely laments the passing of Dynasty, the fact that this country is becoming a police state, the war in Ukraine or other important developments that give little cause for hope.

We, the people who consider ourselves the carriers of such values, have done little to extend them to the vast community of post-Soviet peoples. Some have done everything in their power, devoted their whole lives to that task. But it was not enough. Civil society is not a given. It only results from achieving a certain degree of political development. Sometimes it does not exist at all. The world is full of countries with large populations but no signs of civil society. State-controlled television trumpets daily and in every possible way that Russia is not the West. However, it never explains why because that would require honestly admitting a very "inconvenient truth" — namely, that Russia has yet to pass through numerous phases of economic and political development that the West has already traversed. That is why "Russia is not the West," and not because of some inherent superiority or deeper commitment to "traditional values." It is not that Russia is a laggard — it is just different. It combines features common to the weaker sub-Saharan African countries with other features more akin to the West — and it is unclear which is in greater proportion. Of course, that is not the most pleasant topic for a country that has spent the last 300 years pretending it belongs in the European circle.

The former Soviet republics experienced the dissolution of the institutional and ideological framework of the Soviet Union much as the African states did decolonization. In both cases, many people thought that rapid development and prosperity would automatically resolve long-standing problems and prevent the burden of resurgent empire. And also in both cases, it seemed as if the collapse of empire had left behind citizenries whose members held little in common. The belief that post-Soviet Russia would immediately build up a functioning Western-style social and political culture was just as unrealistic as the expectation that a re-evaluation of colonialism by postwar Western states would lead to a breakthrough in the development of their former colonies.

In order to witness a groundswell of protest against the closure of Dynasty in 2015, there would have to have been far more than seven lonely individuals standing on Red Square in 1968 and protesting the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. Civil society does not just grow out of nothing. It must be cultivated. Democratic human rights activists did much to achieve that during the Soviet and post-Soviet periods, but their miniscule numbers in relation to the giant and largely indifferent majority remain approximately the same today as they were back in 1968. And if Russia's people of conscience never built, or never finished building civil society, they should not be surprised if someone else — such as President Vladimir Putin — co-opted that process for his own ends.

Consciously or not, Putin achieved much greater success in creating a community that includes practically the entire population of the country. This is probably because he did a better job of choosing the correct questions and giving more exact answers to them than did the former Soviet dissidents. Consider the fact that after the fall of the Soviet empire the people of Russia did not unleash a street carnival in celebration of achieving their long-awaited independence. The people were actually more disappointed than jubilant: after all, in a sense it was their empire that had failed, and not someone else's. That feeling of resentment over "lost empire" gave Putin a more powerful key to the people's hearts than Soviet dissidents could have ever dreamed of having with their idea of the rule of law. Let's be honest, Putin achieved what the advocates of Western values could not: Russians have been more united during these last 18 difficult months than during the whole of the post-Soviet period. As they say, the person who holds the flag determines what is written on it.

As usual, though, that success is tempered by a few caveats. First, history is replete with the flags of societies that corralled citizens into ghettos for championing human rights and higher education. Second, the person holding the flag can only do so as long as he sincerely believes in the motto emblazoned on it. If he does not, he suffers an unenviable fate once that lie is exposed. And third, Putin has adorned his flag with a reiteration of the principle the West heralded approximately 100 years ago — namely, the idea of national sovereignty and the sanctity of the principle of non-intervention. Paradoxically, it is this principle of non-intervention that the Kremlin is attempting to drive home with its undeclared war in Ukraine.

However, Russian leaders simultaneously declare the wholly incompatible goals of isolationism from and cooperation with the global economy. With Kremlin spin doctors leading the call of "Crimea!" in order to shore up support for Putin's confrontation with the West, they have spawned a sort of Frankenstein's monster — hardly a healthy beginning for a country seeking to take its place among the most developed countries of the world, and not among the most backward.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.