Some of my friends and colleagues are still talking about Russia’s “shame” when it decided to allow troops from NATO-member countries to take part in the Victory Day parade on Red Square, although the event happened more than four months ago. “What is going on?” they still cry. “We let the enemy march right into the very heart of Russia — into the holy of holies, right up to the Kremlin gates!”

What is most interesting, though, is that the people who scream the loudest about the dangers of Russia being “encircled” by NATO are the same people who gladly take vacations in NATO countries, buy real estate there, send their children there to study and even root for those countries’ football teams.

The Czech Republic is a good example. Although the country is an active participant in NATO, Russians have practically “occupied” its spa town of Karlovy Vary. Popular Russian songs are heard in the evenings along the central wharf, all the signs at the town’s resorts are written first in Russian and then in other European languages, and the restaurant menus all cater to Russian tastes. In Britain, nearly half the castles are now owned by Russian oligarchs, and it is more common to hear Russians swearing on Trafalgar Square than the native Cockney banter. Hordes of Russians buy up wine, perfume and cheese in France, and in Italy they besiege the expensive boutiques of Milan.

And the United States — the heart of NATO and ostensibly Moscow’s least-loved member country — attracts tens of thousands of Russian visitors every year like a powerful magnet. Hollywood films dominate Russia’s movie theaters and television screens. Moreover, several million Russians now call the United States their home. Among the immigrants are hockey stars, world-class computer programmers, composers, businesspeople, singers, political scientists and journalists. Even former diplomats, Soviet-era professors who taught Leninism-Marxism and the history of the Communist Party and former Soviet and Russian intelligence agents have relocated in huge numbers to the United States and other NATO countries. Meanwhile, Russia imports billions of dollars of goods from NATO countries, such as medical supplies and equipment, computers, mobile phones and other electronic gadgets, cleaning systems, automobiles and airplanes.

For all the bilious demagoguery we hear about NATO and its evil intentions, there seems to be a lot of admiration and warm feelings toward the alliance’s member countries.

In short, Russia needs those countries, it depends on them, and it is attracted to them. That being the case, why do so many Russians despise and fear NATO so much? Since the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, has NATO ever called Russia its enemy? Is the alliance planning to invade Russia and seize its gas, oil and metals resources? If Russia really believes that such a threat exists, it should immediately stop flirting with the enemy, using their products and buying up Western castles and football teams. Russia must go on the defensive and prepare for war with them. It must form an alliance with North Korea, Iran and even al-Qaida to defend against NATO encirclement or invasion.

Instead, Russia has a self-contradictory, schizophrenic relationship to NATO. It is friends and enemies of NATO countries at the same time. It loves them and hates them, distrusts them and relies on them. There are a number of factors that play a role in this phenomenon: the inertia of Cold War animosities and rivalries; Russia’s wounded pride over the collapse of the Soviet Union and the loss of the country’s superpower status; its chronic social and economic backwardness; cultural differences; and, to be fair, the West’s historically arrogant attitude toward Russia. The other important factor is that Russia — like many other countries, including the United States — needs to have external enemies to help rally the people and divert their attention from domestic problems.

Meanwhile, Russia faces a deluge of real threats that have nothing to do with NATO whatsoever. The raging forest and peat bog fires that suffocated millions of Russians this summer is a good, recent example. It turned out that Russia’s firefighting capabilities were woefully unprepared, underfinanced and understaffed. Russia has an abundance of intercontinental ballistic missiles but an acute shortage of firefighting equipment. Does this make sense?

In addition, Russia is crippled by other internal problems such as high levels of drug addiction, poverty, corruption, a huge gap between the rich and poor, and “experts” wholly lacking in professional qualifications because they purchased their college diplomas on the Internet. There are counterfeit medicines, substandard food products, ethnic and sectarian strife and chauvinism, alcoholism, substandard hospitals and schools, and, of course, terrorism.

Russia needs to forget about NATO as an “enemy” and mobilize its resources to fight these pressing internal problems. And because some of these issues clearly cross borders into Europe and the United States, Russia should work with NATO countries to fight these problems together.

There were several tragic periods in Russian history when the country all but ignored its internal problems and spent most of its resources battling external, mythical enemies. This ended in one tragic result — collapse of the country. It happened in 1917 and again in 1991.

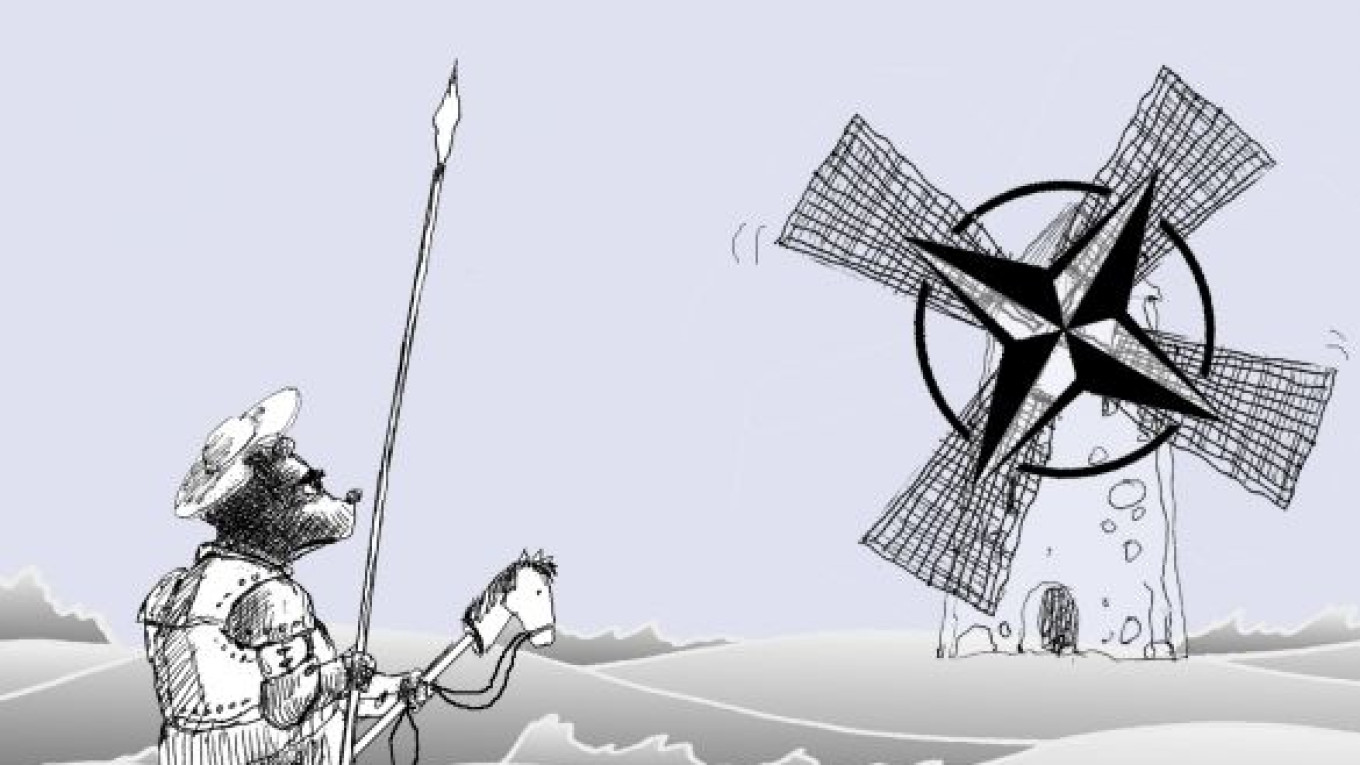

During the second half of the 20th century, the Soviet Union had built enough missiles to easily destroy any external enemy. But those missiles remained unused in their silos while the Soviet giant collapsed under the weight of its massive internal problems. It is time Russia learned not to tilt at windmills, but to confront the real threats to its national security, if not its very existence as a sovereign country. In this context, it is appropriate to repeat the warning of 18th-century French philosopher Charles de Montesquieu — a maxim that has particular relevance to Russia’s troubled history: “Small counties perish from external enemies, and large countries perish from internal ones.”

Imagine for a minute that the dreams of Russia’s NATO bashers come true: that NATO is dissolved. They will dance in the streets, singing, “Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead!” But once the initial ecstasy passes, they would need to ask themselves, “How will European security be weakened without NATO?” Without a basic system of collective security, a dangerous cycle of rivalry, mistrust and rearming would likely be unleashed among European NATO members. Without NATO, Germany will certainly look much more suspiciously at France than it does today, for example, as will France at Britain and Poland at Russia. Europe could once again become a cauldron of simmering conflicts. History has shown that in this environment, all it takes is one lit match to ignite a new military conflict. And as we know all too well, during a war in Europe, it is Russia that suffers the most. The sacrifice Russians made in the two world wars should be enough to finally bring that lesson home.

Yevgeny Bazhanov is vice chancellor of research and international relations at the Foreign Ministry’s Diplomatic Academy in Moscow.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.