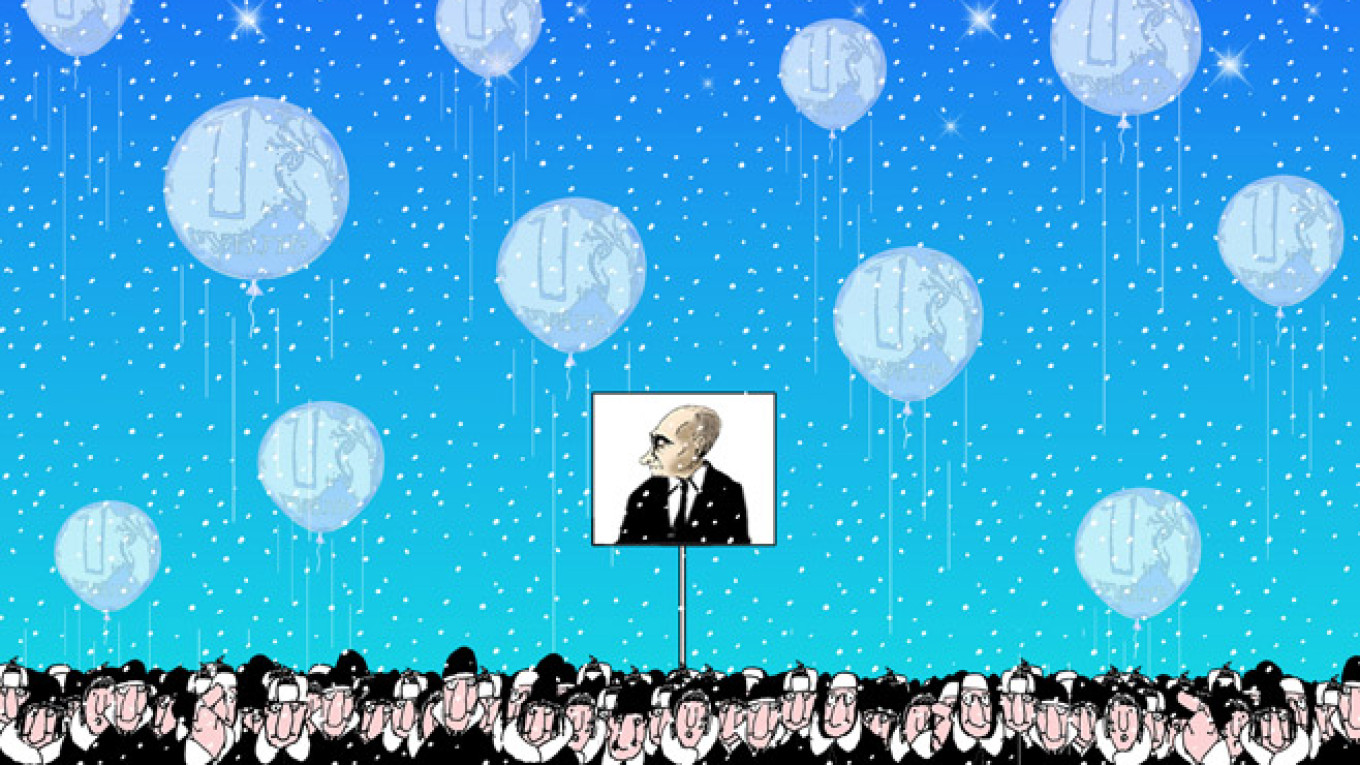

In recent weeks, news from around the country has shown panic among bank depositors and long lines at currency exchange points. Reports on the exchange rate consistently make headlines. It might seem as if the entire Russian population does nothing but monitor the ruble's dramatic rise and fall against the dollar.

If almost any other country besides Russia were to experience such a rapid devaluation of its currency, its government or central bank head would almost certainly be forced to resign. However, during a three-hour news conference, President Vladimir Putin supported his government and the Central Bank for, "on the whole," taking the right actions.

In fact, Putin did not even deign to scrutinize the foreign exchange market, or to announce any measures for radically reforming the country's economic and financial systems. Putin apparently believes that the system he created is functioning properly and coping adequately with the situation.

I must admit that Putin has always possessed a very keen sense of the public's mood, and in downplaying any threat from the currency and financial crisis, his rhetoric matched the feelings of the overwhelming majority of Russians.

Even if the ruble were to fall even further, it would not provoke the Russian people to take to the streets in protest. The most they would do to adjust to the rapidly deteriorating situation is to buy durable goods such as cars, apartments, and home electronics — or sacks of buckwheat for those of more modest means — to hedge their savings before prices begin to rise, or else convert their rubles into dollars and euros.

Russia has experienced several devaluations of the ruble in the post-Soviet period. In fact, the devaluation in 1998 was more severe, and today's situation is better by comparison. Never once did financial turmoil spark significant social, much less political protest, even back when the opposition was stronger and more organized, and the many restrictive laws against protests that legislators have passed in the last two years were not yet in place.

The main reason Russians remain "unmoved" with regard to exchange rate fluctuations is the fact that the vast majority live entirely with rubles and do not even hold savings accounts in foreign currencies. Russians currently have about 16.8 trillion rubles ($259 billion) in bank deposit accounts. That figure has remained stable overall since early 2014, even after many people initially withdrew savings when the fighting in Ukraine broke out in March, but then began depositing those funds again in summer.

Over the past four years, foreign currency accounts ranged from 17 percent to 19 percent of all deposits, rising only slightly to 22 percent now. In other words, Russians did not rush en masse to convert their rubles into other currencies.

However, according to various estimates, Russians might have as much as $80 billion in cash stashed away at home, as compared to the estimated $50 billion dollars that Chinese citizens are holding for a rainy day.

However, that impressively large 16.8 trillion rubles in deposits is owned by a relatively small number of Russians. According to state pollster VTsIOM, 71 percent of Russians have no savings at all, and only about 10 percent hold actual savings accounts — as compared to accounts used only for receiving salaries and paying bills.

The average Russian considers actual "savings" to begin at the modest figure of 250,000 rubles ($3,900). Much of that money is kept at home, in preparation for a major purchase. According to various surveys, only 4 to 7 percent of the people keep their savings in foreign currency. The rest prefer the ruble, the currency they receive their salaries in, and in which they pay for goods and services.

Fewer than 2 percent of Russians earn salaries in a foreign currency. My guess is that the sentiment "I have never held any foreign currency and the price of the dollar does not interest me" is very widespread in Russia.

At the same time, more than half of all Russians have been monitoring the ruble-dollar exchange rate, but primarily as an indirect indicator of the state of the economy. Of course, devaluation leads to higher prices, and especially for food — a commodity that concerns everybody.

On average, Russia imports 30 percent of its foodstuffs, but that figure increases to 60 to 70 percent in large cities — and food prices are expected to rise by 25 to 35 percent in the coming months. However, even that major rise in prices will not make people take to the streets in protest because such hardships are not surprising or new for Russia.

Now, paradoxical as it might seem for the Western mentality, the Russian president and government enjoy the trust of the population at a level unprecedented in the post-Soviet period — against the backdrop of a confrontation with the West in which the majority believes this country's policy was correct from the start and the West holds an unjust and hypocritical attitude toward Russia.

According to a Levada Center survey conducted in late November, 80 percent of Russians trust the president — a 150 percent increase over one year ago. During the same period, the number who feel that Putin is untrustworthy fell from 12 percent to just 4 percent.

And, in contrast to previous years, the rise in support for the president was accompanied by a corresponding rise in confidence in other government institutions. Last year only 30 percent of Russians had confidence in their government. This year that number stands at 46 percent.

The same phenomenon applies to attitudes toward the Russian Orthodox Church, the army and security agencies. With the ongoing war in Ukraine that state-owned television continues to portray as the main news story in the country, Russians believe the authorities so completely that most people do not yet consider the dramatic battle between the ruble and the dollar worthy of serious concern.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.