Russian politics are never boring. No sooner had the dust settled after the departure of Deputy Prime Minister Vladislav Surkov than New Economic School rector Sergei Guriev left the country, slamming the door on his way out.

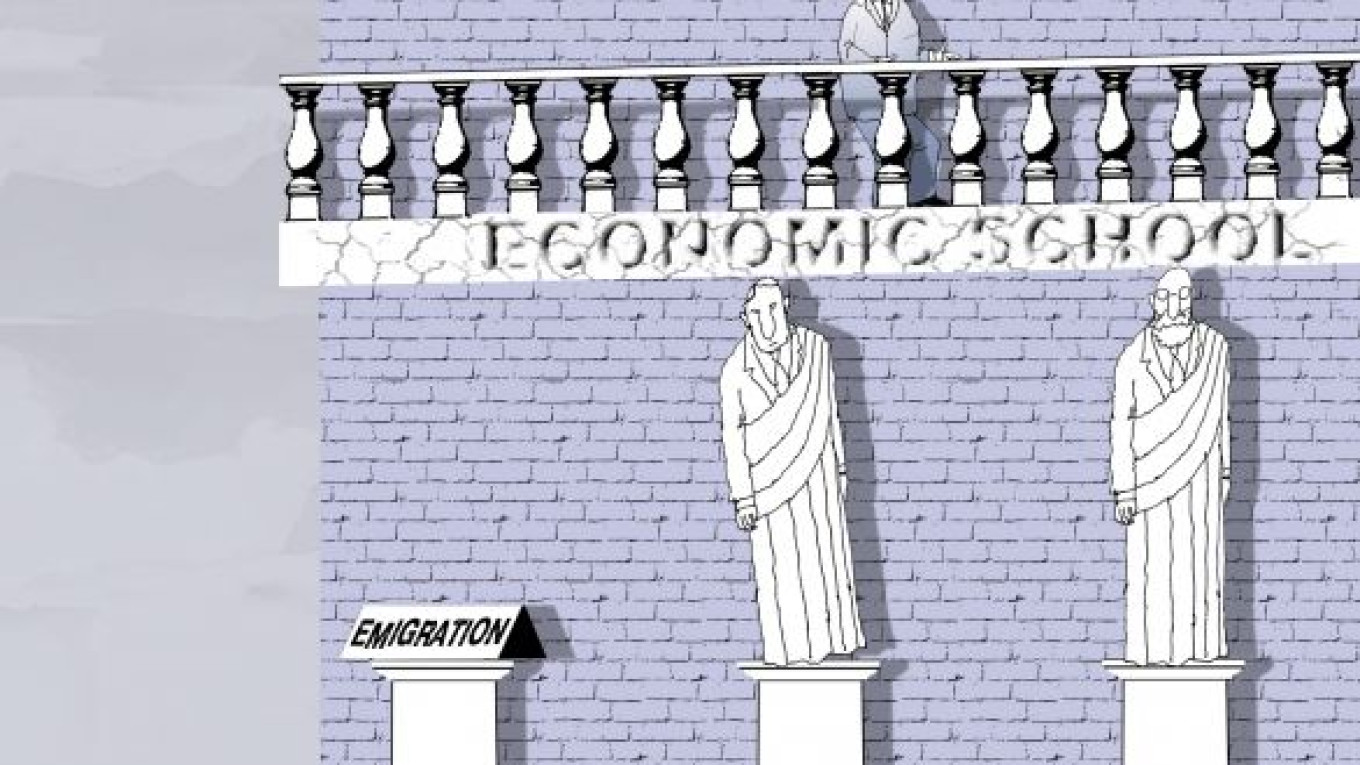

Guriev's exit might not have attracted so much attention if he were just an ordinary university president, but Guriev is the rector of the top economics academic and research institution in Russia. The New Economic School is arguably the most successful post-Soviet project in terms of higher education in economics. Prestigious international journals consistently rank the New Economic School as the best Russian economics institution of higher learning because of its prominent faculty, curriculum, job placement of graduates, system of financing and quality of research. Notably, when? U.S. President Barack Obama visited Russia in July 2009, he chose the New Economic School to deliver his speech.

Guriev is an icon of Russian economic thought, but he is a liberal icon who is oriented toward the West. Guriev left Russia just before the opening of the St. Petersburg Economic Forum, where he is a regular key panelist. At the St. Petersburg forum, as well as other economic and investment forums where Guriev is a fixture, Guriev tries to tell Westerners that the investment climate in Russia, while difficult, is improving. He has always exuded optimism, particularly in the role as one of former President Dmitry Medvedev's top economic advisers. He was bullish on the Skolkovo project and upbeat about the creation of the so-called Open Government. It might seem naive, but that optimism was based on the belief that these projects would in time lead to a more fundamental modernization of the economy. But Guriev also spoke courageously and openly about the shortcomings of the system. Although he generally remained loyal to the system he critiqued, Guriev stepped over the boundary when he openly professed his support for anti-corruption whistleblower and opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who is now being tried in Kirov on corruption charges.

In the wake of Guriev's resignations and departure from Russia, several pro-Kremlin propagandists were even quick to accuse him of having plotted against President Vladimir Putin. One such pro-Kremlin political analyst, Sergei Markov, was happy that Guriev would no longer advise government leaders. "Many people believe that the New Economic School … was the channel through which the Western political and economic elite exerted its influence on Russia's ruling circles," Markov said. "They were increasingly opposed to Putin's attempt to strengthen the role of the state, restore its sovereignty and orient state policy more heavily toward social needs. Sergei Guriev was the intellectual center of that group which developed and implemented a project to replace Putin with a more easily controlled politician. … The Bolotnaya protests were a key element of this plan, and this group poured enormous resources into it, including budgetary funds under its control as well as money from groups of oligarchs," Markov said.

According to this logic, the New Economic School, Skolkovo and several other organizations with close ties to Medvedev were financed by the opposition.

Apparently, the Investigative Committee reached the same conclusion, and it was pressure from that body that ultimately prompted Guriev to resign. This was part of the overall attack on Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and the remnants of his "liberal circle." Investigators reportedly questioned Guriev in connection with a report he co-authored that claims the second criminal case against former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky had been fabricated. It turns out that investigators have searched or interrogated everyone involved with that report on the suspicion that its conclusions were paid for by Khodorkovsky in an attempt to clear his name. If authorities wanted, they could have charged Guriev with obstruction of justice in a third legal case against Khodorkovsky, which many believe is in the planning to keep him in prison well past 2014, when he is scheduled to be released. The allegations against Guriev involving the Khodorkovsky report are highly dubious, but it is possible that Guriev simply got spooked at some point, prompting him to write on Twitter — and later delete — "It is better in Paris than in Krasnokamensk," a reference to the remote Siberian city where Khodorkovsky was imprisoned following his first conviction. And the very fact that such prominent liberals as Anatoly Chubais, Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov and Open Government head Mikhail Abyzov reportedly approached Putin on Guriev's behalf would indicate that Guriev's fears were justified.

But there is also a far more prosaic reason that might explain Guriev's decision to leave Russia. He could have simply grown tired of promoting a stagnant Russia to Western investors, or he got sick of giving sound advice to Russia's leaders, only to see it either ignored or poorly implemented. Yes, Guriev told The New York Times on Friday that he feared for his freedom and would not return to Russia in the near future. But what he did not mention was that he had been flying to Paris every weekend to be with his family, and that his wife, who has taught at a leading school of economics in Paris for the past three years, had become fed up with their remote lifestyle. Now their family is finally united. And in the final analysis, that is more important than all the political intrigues combined.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.