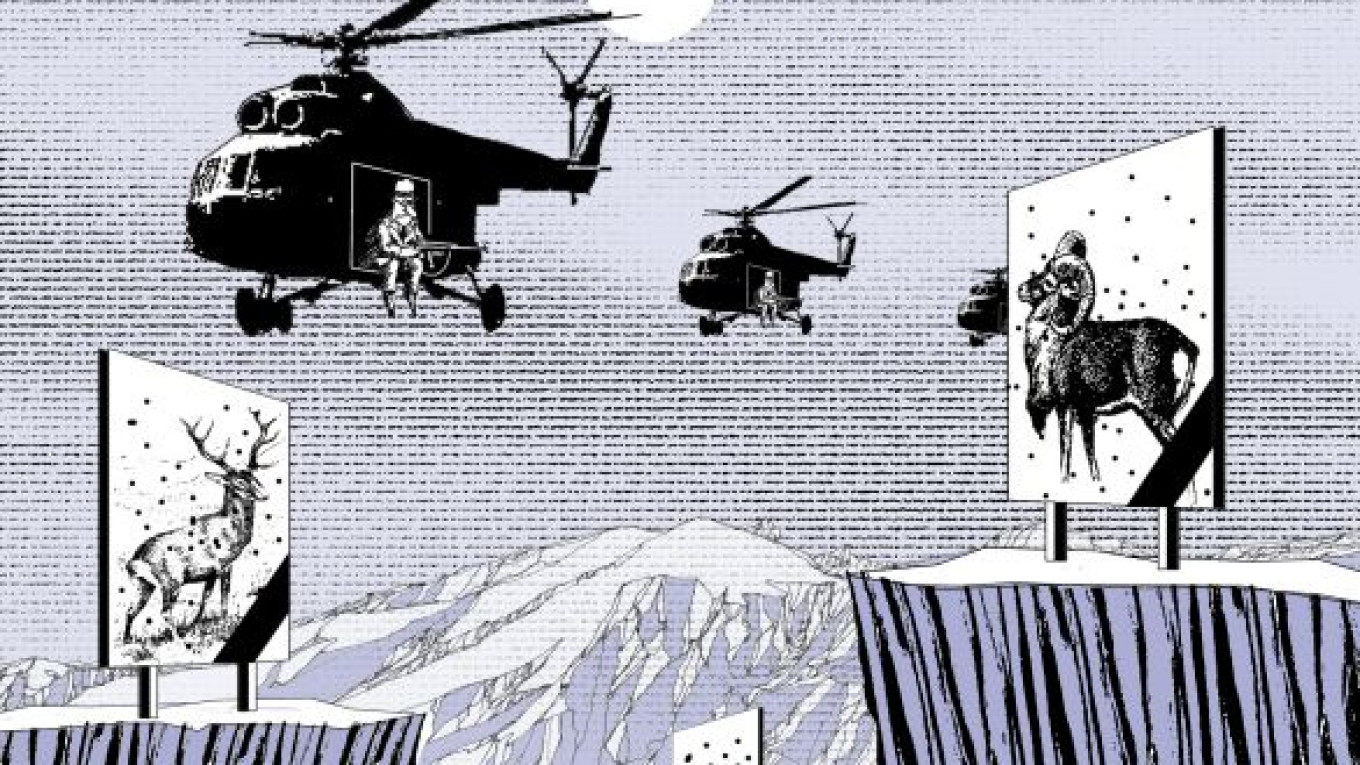

In January 2009, in the Altai Mountains near the border with Mongolia, a helicopter owned by Gazpromavia crashed on the slopes of the Black Mountains, killing seven of the 11 passengers and crew. The list of people on that ill-fated flight included presidential envoy to the State Duma Alexander Kosopkin, who was killed. Rescuers found automatic weapons on board the helicopter and the carcasses of endangered argali sheep near the wreckage. Only about 300 argali remain in Russia, and hunting them is strictly forbidden. The case received wide publicity, with journalists dubbing the incident "Altaigate."

Investigators opened a criminal case and charged the survivors of the crash with poaching from a helicopter. The case dragged on for years and was finally dismissed when the statute of limitations expired. The poachers got off with only having to pay fines. As a rule, most cases of "VIP poaching" in other regions end with only a slap on the wrist — and in many cases, not even with that.

During a trip on horseback along the densely forested ridgeline of the Ust-Koksinsky District of the Altai republic, the area adjacent to the scene of the helicopter crash, I saw for myself what happens when VIP poaching goes largely unpunished. It looked like a ghost town in terms of wild animals. What I did see, however, were hundreds of rope and steel traps placed along the animals' trails that were left by locals and woodsmen hoping to cash in on the pelts and valuable musk glands of the deer.

The region was once the main jewel in Altai's amazing natural splendor. You can still find the greatest mountain of Siberia, the Belukha, along with the enchanting Talmene and Multinskiye lakes. Local residents explain that the indigenous Siberian red, roe and musk deer have been almost completely wiped out along the Terektinsky and Katun ridges, with the exception of a few hard-to-reach tributaries of the Akkem River.

When I was in remote areas of the Altai republic in September, I saw helicopters fly to the area's hunting grounds every day. Hunting from helicopters is not only illegal but also the most barbaric and inhumane method of killing animals. Helicopters descend on the animals with a load roar of the engines, while the "hunters" stand at the ready with rifles in hand. Instinctively fearing an attack from above, the panicked animals race into the open where they are shot down by the cold-blooded killers. Their bloody carcasses are dragged on board to be carved up later.

Local and federal authorities do not resist the widespread poaching in the Altai republic. On the contrary, government officials are some of the more ardent lovers of hunting rare animals. Local hunters, who would also love a chance to poach, are not allowed anywhere near the best hunting grounds, which are reserved for VIP officials.

Is it possible to save the wildlife that remains? Yes, but it would require drastic measures:

The first step should be a total ban on hunting in protected wildlife areas. Authorities could accomplish this by recruiting and arming experienced rangers, including those from the nearby nature reserve who would patrol the entire region.

Second, the borders of the Katunsky Reserve would have to be expanded to include enough of the forest lands to allow the wildlife population to grow.

Third, an effective wildlife protection service must be created with the participation of a newly reorganized association of hunters.

Fourth, an annual census of the number of animals must be conducted, with strict hunting quotas for locals and commercial hunters and only in areas that do not threaten the existence of protected species.

Fifth, helicopters must be prohibited from flying over the area during hunting season.

Sixth, more land must be made available to the argali so that their main migratory paths remain intact.

If these measures are adopted, the taiga of the Altai Mountains, with its vast cedar forests and its wide, fertile meadows, will quickly regain its former beauty as a pristine nature reserve. But the main thing is that everyone who visits this region comes to see not only the rich cedar, larch, meadows and mountains but also the beautiful animals grazing on them. Currently, there are no animals to see.

With the destruction of wildlife comes the inevitable degradation of the region's flora. That, in turn, will spell the death of the Altai republic as Russia's precious natural wonder and portend mankind's descent into destruction, barbarism and emptiness. We need to stop this descent while we still have the chance.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio and is a co-founder of the opposition RP-Party of People's Freedom.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.