By June 19, President Vladimir Putin is expected to sign a decree that will officially kick-start the campaign season. Within a few days, all the parties taking part in the election will host conventions and declare their list of candidates.

These State Duma elections will be the first time Russians take part in a nationwide vote since the Kremlin annexed Crimea in March 2014. The last time Russia held a parliamentary election, in 2011, Moscow erupted with the biggest demonstrations in its post-Soviet history. With the country facing a bitter economic crisis, the Kremlin is determined to avoid anything close to such a scenario this autumn.

For ruling party United Russia and its curators, this requires a change in tactics.

United They Fall

Russia's recession seems to be taking its toll on United Russia. A poll conducted in May by Moscow-based pollster Levada Center found their approval ratings fell from 42 percent to 35 percent on the eve of their campaign launch. This is partly due to the waning of the "Crimean effect," the euphoria that stemmed from Russia taking the peninsula from Ukraine. "There is nothing to replace it with," says Alexander Kynev, a professor of political studies at Moscow's Higher School of Economics.

Analyst Alexei Makarkin, meanwhile, links the falling ratings with a returning and growing separation between the president's approval rating against those of the rest of government officials. "In the aftermath of Crimea, everybody's ratings shot up," he says. Traditionally, Makarkin explains, Duma deputies are unpopular figures. "People don't like them, they think they are detached from society," he says. Crimea changed this, at least temporarily. Following the annexation, Duma deputies became respectable figures for the first time. Two years later, their ratings are coming back down again.

But for Kremlin strategists, the drop in ratings is of little concern.

Indeed, Konstantin Kalachyov, director of Moscow-based Political Expert Group, argues United Russia's position is, in fact, unexpectedly resilient. One place where this is particularly visible, he says, is in the Yaroslavl region. The region, which lies 250 kilometers northeast of Moscow, is one of the least fertile grounds for United Russia support. It is also home to an opposition mayor, arrested three years ago on corruption charges. Despite this, the party is still polling there at 38 percent. "If that's their rating in their worst region, then there is no problem," says Kalachyov.

Changing the Rules

The Kremlin also foresaw a fall in the party's popularity and responded by changing the rules of the game. This year, Russia will revert to an electoral system it has not used since 2003. Half of the Duma's 450 seats will be elected using proportional representation from party lists — where approval ratings matter. But the other half will be chosen in single-member constituencies using a first-past-the-post system ?€” in the same way parliamentary elections were held between 1993 and 2003.

Amid a prosperity boom in the mid-2000s, United Russia excelled in the party lists. The Kremlin assumed parliamentarians elected through single-member constituencies were harder to control and switched to an electoral system relying purely on party lists. But the 2011 election proved to be a failure for the party: United Russia performed badly and the Kremlin decided to switch back to the old voting system.

Makarkin believes a return to the old system will benefit the Kremlin again. Voters, he says, trust candidates associated with United Russia have the resources to find financial solutions to local issues. "The opposition can talk nicely but these guys can fix real problems," he says. This approach reflects Russians' split mood toward the government: hostile but reliant.

What's more, some pro-government candidates will disguise themselves as independents. "In the last few years, United Russia candidates shied away from their party labels and tried to hide them during elections," says political consultant Mikhail Vinogradov.

This tactic proved very effective during the 2014 Moscow City Duma election, in which all of the seats were chosen in single-member constituencies. Almost all of the candidates Moscow authorities were relying on made it through by not affiliating themselves publicly with the ruling party. The opposition was not even there, it failed to provide the necessary number of local signatures to take part.

The same scheme will be used in September. Many pro-presidential candidates will represent the All Russia People's Front, a movement established on the eve of Putin's return to the Kremlin in 2012. It remains unknown whether they will join United Russia in the newly formed Duma or form a separate faction. Whatever the case, the Kremlin is set to keep control over its majority.

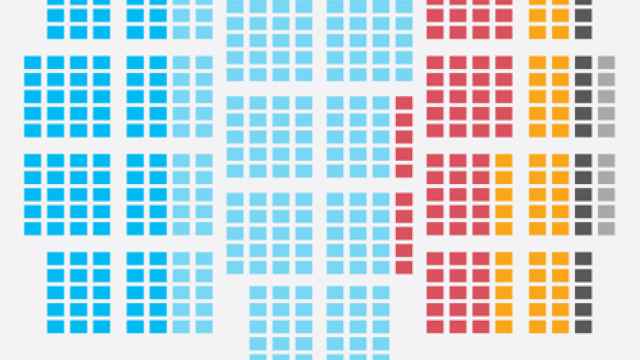

Possible new State Duma composition

No Room for Real Opposition

Political analyst Abbas Gallyamov predicts the ruling faction ?€” or factions ?€” will receive up to 80 percent of the Duma seats allocated through single-member constituencies. Most analysts agree with these estimates. This prediction would leave the ruling party with an overwhelming majority. If it wins around 45 percent of the vote, the open pro-Kremlin majority will balance on the edge of a constitutional majority (two thirds of the Duma).

The 2011 election which ended in protests has left a haunting mark on all sides of Russia's political system. In the five years since, authorities have forced the opposition movement born out of the protests virtually underground.

Alexei Navalny, who became an opposition leader during the protests, was barred from registering in this year's election. Two opposition parties led by Yeltsin-era politicians ?€” Parnas, headed by former Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov, and Yabloko, led by economist Grigory Yavlinsky ?€” are taking part in the election. But, according to current polls, neither of them will make it into the Duma.

This scenario leaves the next Russian parliament without any real opposition voice. All other parties entering the Duma ?€” the so-called "systemic opposition" ?€” support Putin. This parliamentary opposition is currently made up of three parties: LDPR, led by Russia's veteran outspoken politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky; the Communist party, led by Gennady Zyuganov since 1993; and Spravedlivaya Rossia, led by Putin-loyal bureaucrat Sergei Mironov. The systemic opposition bargains on certain issues on occasion, but is firmly under Kremlin control.

Catching the Mouse

Analysts say the Kremlin may be interested in a fair vote count this year, if only to avoid a 2011-2012 scenario and to send a message to the West that there is consensus in Russia. "They realized that people care about how the votes are counted," says Makarkin. The first sign of this new, caring approach came in April, when former human rights ombudswoman Ella Pamfilova was appointed head of the Central Election Commission.

When it comes to elections, Vyacheslav Volodin, deputy chief of staff of the presidential administration, enjoys Putin's total confidence. "He has been given carte blanche," says Kalachyov.

For Volodin, the priority is for the elections to run smoothly and to leave no room for anyone to question the result. "In some ways, Volodin is more of a pluralist," says Kalachyov. To illustrate his point, he cites an example in Siberia's Irkutsk, where the Communist Party candidate defeated the incumbent governor and has not been touched since.

This change in strategy will enable the Kremlin to silence the opposition more effectively while simultaneously appearing to be open to pluralism.

Volodin's game plan, Kalachyov says, is best described with a Chinese saying: "It does not matter what color the cat is as long as it catches the mouse."

Not wearing a United Russia badge does not mean being insubordinate to the Kremlin anymore.

Contact the author at o.cichowlas@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter at @olacicho

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.