Urban was a quintessential survivor -- a Jewish doctor who lived through the Holocaust and the gulag. In 1980, he wrote an autobiography, titled "Tovarishch -- I Am Not Dead," which contained such remarkable stories that some who read the book did not believe them in their entirety.

A decade later, with the opening-up of the Soviet system through perestroika, he had the chance to return to the U.S.S.R. and attempt to find out and prove the truth of his recollections by revisiting the main places of his life and attempting -- with varying degrees of success -- to obtain copies of the security files held on him. He was accompanied by his son, British filmmaker Stuart Urban, who filmed the journeys, revelations and reunions, originally with a view to making a feature film on the story.

That idea is yet to be realized, but in 2007 he released an 83-minute documentary with the same title as his father's book. It goes wider than any feature treatment would likely have done, bringing in the whole historical context, as well as the dynamic of the father-son relationship.

That latter element stands out, given that Garri was clearly a man of personality -- fractious, insistent, charming and garrulous, yet at the same time secretive, even to his son.

The material assembled is varied indeed, from home movies of family life in London from the 1950s onward, to archival footage of the war years, set interviews with Garri and the experience of the return visits to, respectively, Russia, Uzbekistan and Ukraine.

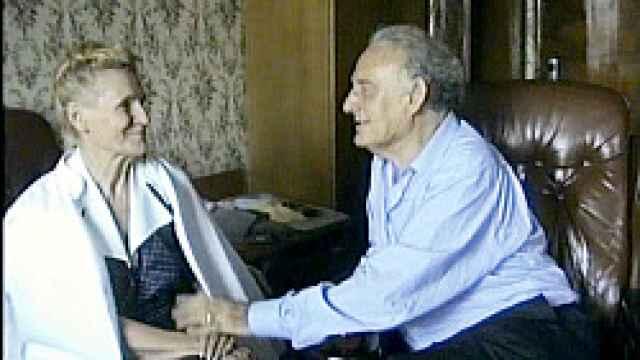

It's those trips that provide the most compelling, and emotionally raw, material. A newspaper advertisement brings a reunion with Garri's wartime sweetheart, Noka Kapranova, the editor of the only Soviet fashion magazine of its time. When he was arrested in 1943 in Tashkent by the NKVD, she persisted in trying to find out his fate and was herself sentenced to eight years in the gulag. The implication is clearly that her sentence was a direct result of her association with him, although it's not stated in the film directly.

Stuart Urban The film reveals a complex relationship between father and son. | |

"She is a noble person who went through extremes of suffering and repression." She lives today, in her mid-90s, on the outskirts of Moscow, effectively on charity. "I think it brought her great joy to watch the film."

Together again in Tashkent, the elder Urban attempts -- somewhat riskily, given the discovery in Moscow that he is still officially classed as an international spy -- to retrieve his file from the local KGB headquarters. Not only is he unsuccessful, he is even briefly arrested, returning to the very building in which he had been tortured, and attempted suicide, in 1943. Getting out involves considerable chutzpah, saying he has the personal telephone number of Uzbek President Islam Karimov, while admitting later that Karimov would have no idea who he is.

The incident reveals perfectly the element of bravado that seems to characterize Urban's life, or what he calls his "very big Jewish balls" (he's no stranger to fruity language, either) and his son describes as being "used to getting his way at every turn."

It also brings to the foreground the complicated emotional dynamic between father and son, with the former repeating the phrase, "I'm doing it for you, my son," an ambiguous enough attitude that resonates throughout the film. It seems that the father's need to go back into his past is genuine, if sometimes slightly theatrical, and ambiguous given that he appears to be both concealing some real details of his life, as well as rediscovering others.

The central mystery of the father's destiny comes down to one thing -- was he just a miraculous survivor, indeed escape artist, of the Soviet regime of the war years, or was he a collaborator, even a spy, with the Soviet authorities? After his failed attempt to flee to Romania in 1939, he was sentenced to five years in the camps in Kolyma for anti-Soviet activities, where, as a doctor, he fared better than most other prisoners.

The following year he managed to escape (or was allowed to escape?), dressed in a KGB uniform, apparently obtained as a result of his considerable charm with the opposite sex, and return to Moscow. Despite his arrest in Tashkent, by the end of the war he was a senior health official in Ukraine, serving under Nikita Khrushchev. One scene has Urban, in a typically pugnacious mood, visiting the latter's grave in Moscow's Novodevichy Cemetery. In 1946, he was able to flee the Soviet regime to Western-occupied Germany, disguised, ironically, as a German prisoner of war.

Stuart Urban Garri is reunited with his sweetheart. | |

The two brothers had no idea that each had survived the war and Holocaust and were reunited only in the early 1960s, after investigators discovered that Menachem was alive in Israel. The latter tells Stuart that he believed that his father had been in Dresden at the end of the war -- further suggestion of collaboration.

The secret remains unresolved, the director admits, though he still hopes one day to find the full security file on his father and to develop the story as the originally planned feature film. In 1992 at Lubyanka, the former headquarters of the KGB, officials apologized to Garri for how he had been treated but were far from forthcoming with facts.

It's only in the documentary's closing scenes, when father and son return to Ivano-Frankovsk and Garri's native village of Bratkovice, that there's a hint of greater revelation. Using his characteristic insistence, Urban persuades the KGB there to release at least a part of his file, while his son is told that "some of the things in it would make your hair stand on end." Tantalizingly, much of that information is missing from Garri's own personal archive after his death in 2004, as if he too had chosen to expunge episodes from his past.

Stuart admits that he was unable to complete the film while his father was still alive and that a first cut that his father saw resulted in a feud. "He thought it might compromise some who had helped him in the security services, or perhaps he was conscious of his own image," the director said.

It's in Bratkovice that the film comes closest to emotional resolution. Garri sits with local villagers in the house of his parents for a farewell meal, managing to forgive, while never losing the resolve to fight. The area was the site of the massacre of more than 100,000 Jews, one of the worst in Europe, though mass burials leave little detailed trace of the dead. Nor can Garri even find the grave of his beloved mother, who had died young, before the war, "in peace."

"Tovarishch" is a film of great depth, and lasting emotional power, that leaves questions open, and personal relationships between father and son -- and other participants -- somehow not finally resolved. The final line speaks much -- that Garri Urban, from his birth in 1916 through to his death in 2004, had a "destiny to live."

For more details on the film, see www.tovarisch.net

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.