Editor’s Note: This is the second article in a series that focuses on three sites of memory in the new Ukraine. The three articles examine connections between memory and national identity and discuss the ways that perceptions of the past have produced debates connected to the ongoing crisis. Read the first article: Ukraine's New Sites of Memory: A Candle in Kiev

President Vladimir Putin may have declared in 2005 that the Soviet collapse was the “major geopolitical disaster of the century,” but the Ukrainian National Chernobyl Museum built in Kiev after 1991 tells a different version of that story. ?

In his March 18 speech about the annexation of Crimea, Putin again declared that the demise of the U.S.S.R., or “what seemed impossible, unfortunately became a reality.” Putin stressed the common heritage Russians and Ukrainians share and how in his view present-day Ukrainian nationalists have hijacked this history to foment divisions. The president declared that he “understood” why Ukrainians sought their freedom in 1991 and that he “respects” Ukrainian territorial integrity — not including Crimea, of course — but he lamented the way some Ukrainians, often backed by “foreign agents,” have turned the common past shared between the two nations into a divisive one.

This is a neat rhetorical trick, but one that also ignores some crucial facts about the Soviet breakup and Ukraine’s role within it. This story is one that begins in April 1986 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and it is a history that has found a home in one of Ukraine’s new sites of memory, the Ukrainian National Chernobyl Museum. ?

Founded in 1992 on the sixth anniversary of the disaster, the museum is located near Kiev’s central Kontraktova Square, in a former fire house. The museum, as its website notes, aims to help visitors understand the scope of the Chernobyl disaster through the fates of people who witnessed the accident, who participated in the disaster’s cleanup, and who suffered as a result of the 1986 events. Many of the displays within the museum speak to a larger and more global aim, seeking to stress the need for greater vigilance to oversee the technological threats to the Earth and to therefore “not let the world forget the lessons of Chernobyl.” Visitors are asked to “keep Chernobyl in the heart,” as one display proclaims.

The bulk of the Chernobyl Museum, however, narrates a very specific history of the event and its subsequent impact on Ukrainian history. The displays focus first on the stories of the first respondents to the power plant fire, who number more than 5000, including the 31 who died from radiation poisoning. The walls of the first room are adorned with their photographs and the museum operates an online version of a “Memory Book” that allows anyone to read their stories.? Other displays focus on the Soviet state’s failure to respond to the unfolding Chernobyl disaster.? Exhibits contain official documents and newspaper articles that explain the initial cover-up. ?

A concrete sarcophagus surrounds the remainder of Chernobyl’s reactor.

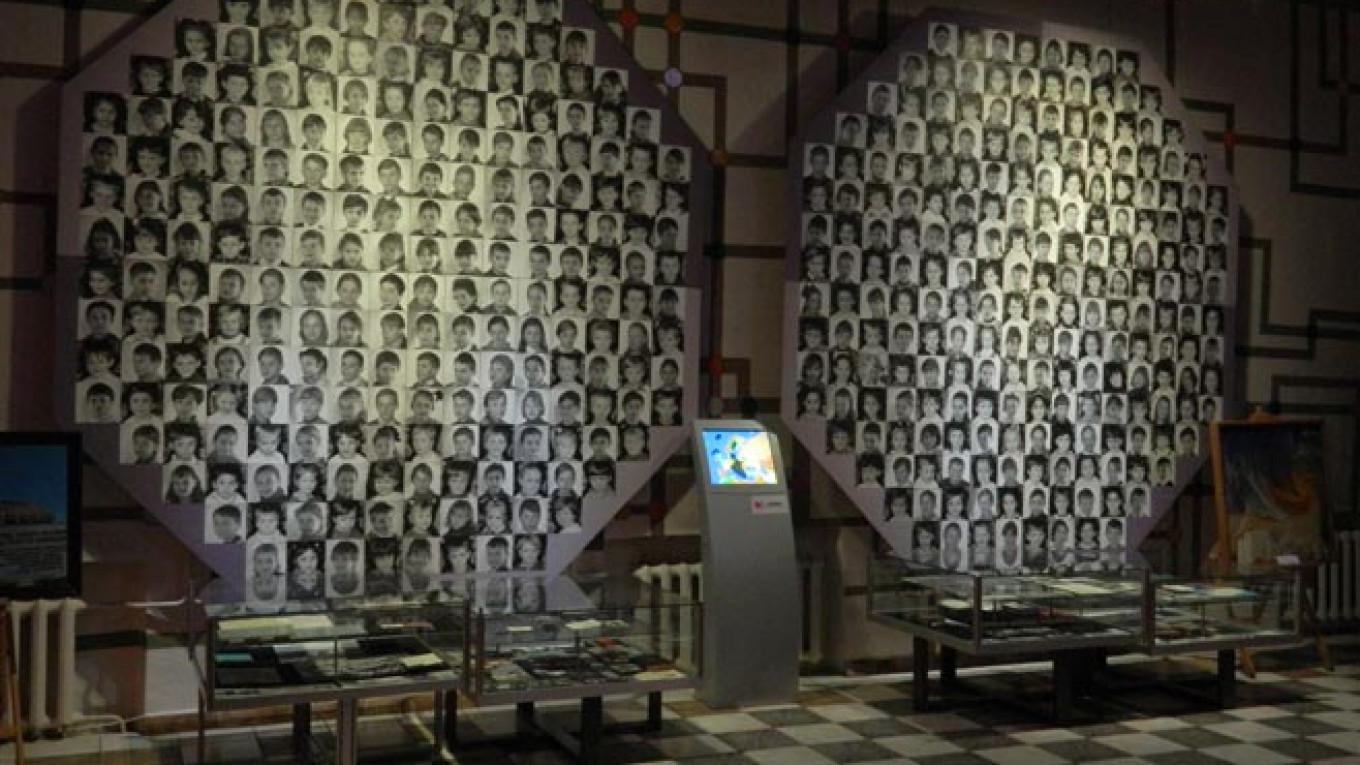

This part of the Museum affirms how the Soviet authorities “did not pass the test of Chernobyl,” as Serhy Yekelchyk has argued in his book “Ukraine: A Modern History.” The cover-up only deepened the effects of the disaster, for radioactive particles leaked into the atmosphere and spread throughout the region. Museum exhibits show photographs of the 1986 May Day holiday held in Kiev, where citizens participated in parades and other activities unaware of the tragedy that had occurred nearby. More focus on the abandoned sites around Pripyat, the nuclear city where most of Chernobyl’s workers lived, and the devastating effects the disaster has had on Ukrainians and Belarussians ever since, with a particular focus on the birth defects and cancer rates among children born after 1986 in the region.? ?

The Chernobyl Museum therefore serves as a reminder of how that nuclear accident galvanized Ukrainians at the time and has stood as the most significant event in recent Ukrainian history.? The story told within the memory site has a clear transnational and even international element to it — clearly many Soviet citizens suffered from the Chernobyl disaster and its lessons are ones we all need to pay attention to — but the center of the history is a Ukrainian one. It reminds visitors of how the radioactive fallout from Chernobyl played a key role in creating a new independence movement in Ukraine. Chernobyl, as the anthropologist Catherine Wanner has written, provided “evidence that Ukrainians would never be entirely safe as a colony of ?Moscow and that an independent state was needed to protect and to maximize prospects for the well-being of Ukrainians.”

For many in the region, Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost was exposed as a lie in April 1986 — as a result, the Communist Party lost a great deal of its legitimacy in Ukraine and more and more Ukrainians began to support independence, culminating in the December 1991 vote for independence supported by 92 percent of voters.

If contemporary Ukrainian nationhood has its foundation in the memory of the Holodomor, which also created a narrative that Ukraine had been victimized by Moscow; it has a second primary foundation in the events of 1986, which complemented the memory of the famine with new memories of radioactive contamination.

Outside the museum’s entrance, a memorial testifies to Chernobyl’s continued significance in contemporary Ukraine. A statue of a mother and her baby flanked by two bells speak to the disaster’s devastating effects and asks viewers to keep Chernobyl alive in their hearts.

Stephen M. Norris is a professor of history and assistant director of the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies at Miami University (OH). Contact him at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.