After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan was on its way to becoming a model of nation-building. Russian officials praised the leadership of the mountainous republic for its wise economic and national policies. The West was delighted with the democratization of the Kyrgyz state, with its separation of powers, increasingly strong parliamentary system and respect for the freedoms of speech, press and assembly.

But Kyrgyzstan ran into a host of problems along its way toward democratization — rampant corruption, sharp social stratification and nepotism. The economy entered a prolonged period of stagnation, and the people got markedly poorer.

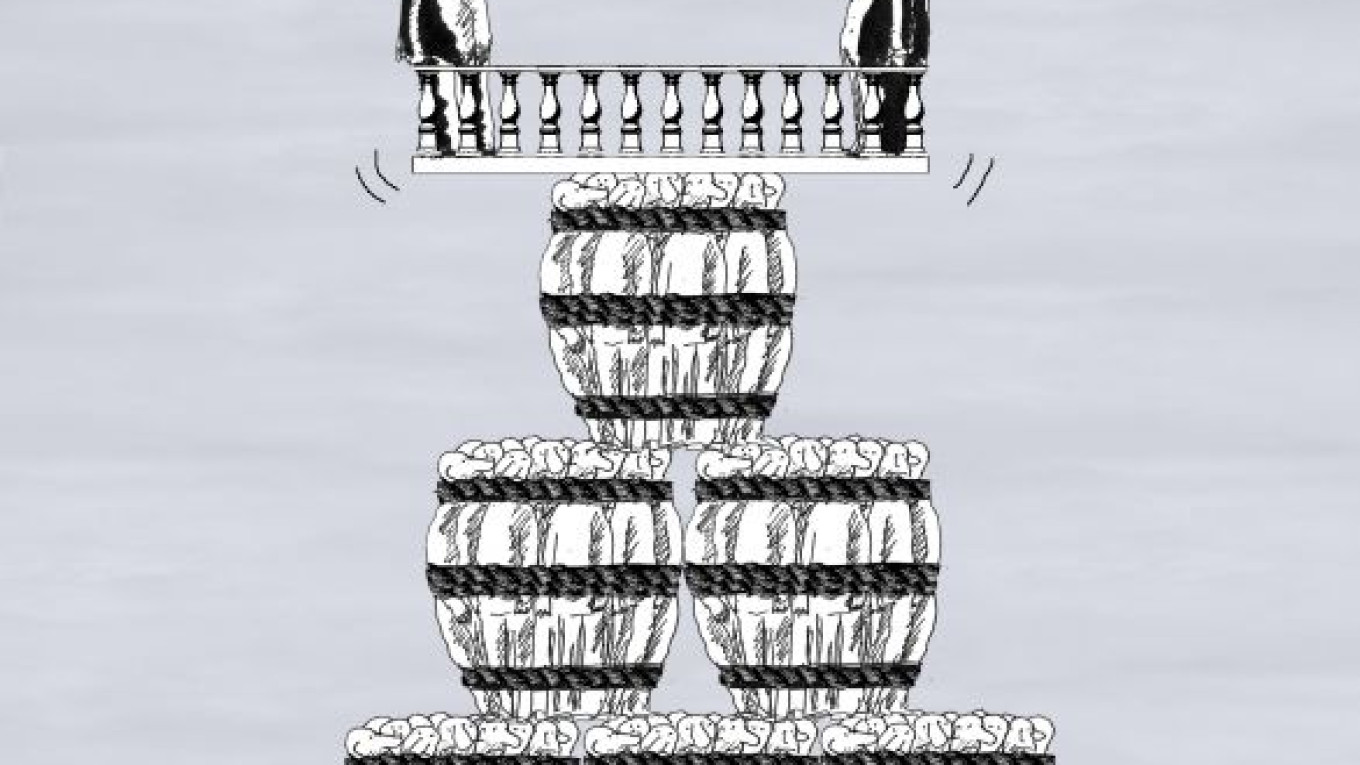

As a result, in 2004, mounting social unrest erupted that led to the ousting of President Askar Akayev, who was replaced by Kurmanbek Bakiyev in the Tulip Revolution. Hopes again soared, but they soon gave way to deep disappointment. Bakiyev and his extended clan behaved like depraved medieval khans, looting the country and exploiting the people, and this sparked the second revolution in a decade.

But Kyrgyzstan is not the only Central Asian state afflicted by severe social and economic ills. Why didn’t Uzbekistan, Tajikistan or Kazakhstan experience the same regime changes? One reason is that there were no periods of democratization in these countries. The people there have always lived under authoritarian regimes, going back to the Soviet era.

Revolutions usually do not break out in countries having long periods of stagnation, but in countries where democratic and economic reforms have begun and where people’s hopes for a better life are raised — and then shattered.

In the early 1900s, the attempt by Tsar Nicholas II to implement economic and political reforms while preserving his autocracy only led to its own collapse. The Soviet Union offers another good example. During the 30-year period of stagnation starting with Nikita Khrushchev to Leonid Brezhnev, few uttered a word of protest. But when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev initiated perestroika and glasnost reforms in the late 1980s — once again, raising the people’s hopes without fulfilling them — the bottom fell out of the Communist system, and the Soviet Union collapsed.

This, of course, does not mean that democracy always leads to false expectations and social upheavals. On the contrary, without democracy, development would either never happen at all, or else it would eventually hit a dead end.

The Korean Peninsula provides strong proof of the evils of totalitarianism. Communist North Korea remains one of the most backward countries on Earth, while people of the same ethnicity created an economic miracle in South Korea. At the same time, however, the economic success of South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore began under authoritarian regimes.

One feature that distinguishes the successful Asian Tigers from Russia or Kyrgyzstan is that the ruling elites have been more concerned with the general welfare of the people and the country rather than in padding their own pockets. For example, the legendary father of Singapore’s economic miracle, Lee Kuan Yew, was able to nearly eradicate corruption, and he started with himself and his inner circle.

How have Lee and other East Asian leaders been so successful at controlling corruption and fostering economic growth? Many believe that Confucian values provide the real foundation —a healthy work ethic, a strong sense of personal responsibility, honesty, humility, and respect for the state, the community and family. Confucianism teaches that morality, fairness and justice must be the guiding principles for ruling the state. Rulers are expected to be paragons of these values; otherwise, they would loose their “mandate from Heaven.”

Another view holds that the Asian Tigers succeeded because they were able to apply Western practices and methods to matters of governance and the economy.

In any case, it is obvious that the economic development of the Japan, South Korea and Taiwan paved the way for subsequent political reforms. They were able to transform their authoritarian regimes into democracies without revolts, riots or revolutions.

In Kyrgyzstan, however, the rulers bathed in a sea of luxury while the people lived in dire poverty. It is no surprise that it ended in a popular revolt two weeks ago.

Yevgeny Bazhanov is the vice chancellor of research and international relations at the Foreign Ministry’s Diplomatic Academy in Moscow.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.