A Ukrainian teenager who had joined the Red Army four years earlier, he was among the first outsiders to glimpse the horror of the death camp in southern Poland, as the troops of the Soviet 322nd infantry division cut the surrounding barbed wire and swept through.

"Some tried to kiss us, but it was uncomfortable, you didn't want to get infected," Vinnichenko recalled, his emotions bouncing between pity and revulsion for the diseased, louse-infested inmates. "They were skin-and-bones, could hardly stand on their feet. ... It's impossible to describe."

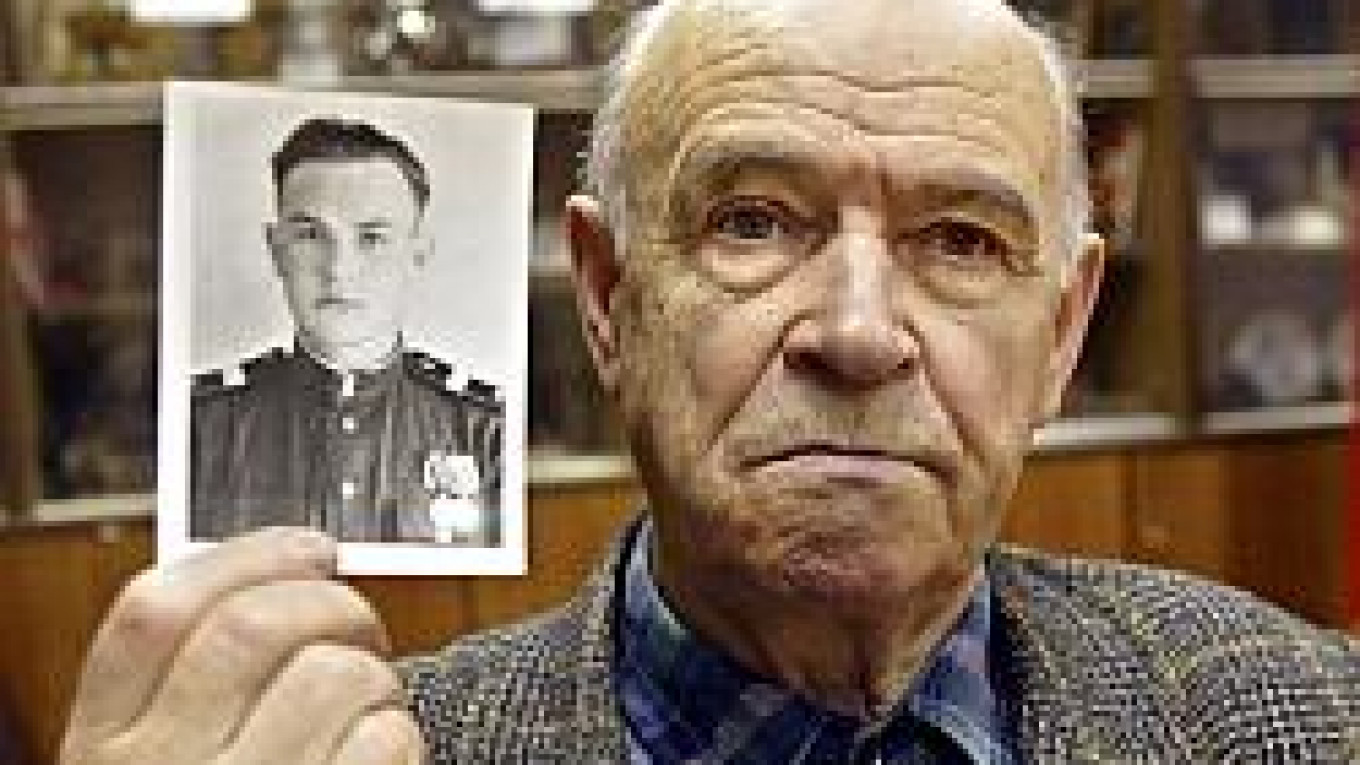

Vinnichenko, 79, heads to Poland this week to attend the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. Alongside the dignitaries from dozens of countries and the camp survivors will be a small contingent from the dwindling number of Red Army soldiers who freed the inmates.

Between 1 million and 1.5 million prisoners -- most of them Jews -- died in gas chambers or died of starvation and disease at Auschwitz. In all, some 6 million Jews perished in the Holocaust.

By the time Vinnichenko's unit arrived, most of the prisoners had been evacuated by the Nazis on death marches as the German troops fled toward Germany. There were about 7,000 left -- "those who couldn't move," as Vinnichenko put it.

"They were holding each other up, they couldn't walk. The Germans just left them behind. They didn't have time to burn them up, to shoot them."

He said his regiment was rushing to the next battle and spent only a few hours in the camp, but he did duck into one barracks.

"There was filth and blood. It was a women's barracks," he said, recalling the sight of hard, three-level bunks covered with straw mattresses. "Some were crying, some were laughing," he said of the inmates he encountered.

Vinnichenko was no stranger to persecution and cruelty: His father died of starvation in 1933, when Vinnichenko was 7, during the state-induced Ukrainian famine that killed up to 10 million Ukrainians. Three of his uncles were sent to Soviet labor camps; his mother fled western Ukraine for a village near Moscow.

"They took the grain away from the peasants. There was nothing to eat. They took the horses, the cows," Vinnichenko said. "Life was hard until the war."

He joined the Soviet Army in 1941, at age 15, after the Germans invaded his homeland -- there was no other choice.

"Whether you wanted to go or not, they picked you up, no one asked. It was the same on the front -- you don't want to fight, you're shot dead by your own men," he said. "The commander's behind, you're in front -- it's only in movies that the commander is in front."

Four thin ribbons on his chest, above his medals, signify the four wounds he sustained during the war -- which he credits for saving his life since he was taken out of combat for long bouts in hospitals. Relatively young compared to the other men and women milling around Moscow's Veterans Council, Vinnichenko nonetheless keenly feels the march of time, the loss of his comrades over the years and the loss of memory.

He admits his recollection of that day of liberation 60 years ago is cloudy; one of the clearest memories is leaving the camp and picking up two bottles of port wine found abandoned in a basement.

"Sixty years have passed, you forget a lot -- and for 30 years, no one showed interest or cared to ask," he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.