Last week Anna Reshyotkina, editor-in-chief of a glossy magazine in Yekaterinburg, was unexpectedly summoned to the Prosecutor's Office for a 30-minute conversation about the cover of the May issue.

She was asked to explain who was responsible for putting a photo of Sofia Nikitchuk — this year's Miss Russia — draped in silky material in the colors of the Russian flag under the headline "The Taste of Victory" on the cover of Stolnik, a local lifestyle magazine.

Prosecutors told Reshyotkina that the probe had been prompted by a request from an unknown individual, who was apparently offended by the cover and thought it desecrated the Russian flag, a criminal offense that carries up to a year in prison under Russian law.

"I was not told the name of the person who was offended by our cover," Reshyotkina told The Moscow Times, adding that the summons from prosecutors had taken her by surprise. Prosecutors have not contacted Reshyotkina since the meeting, she said.

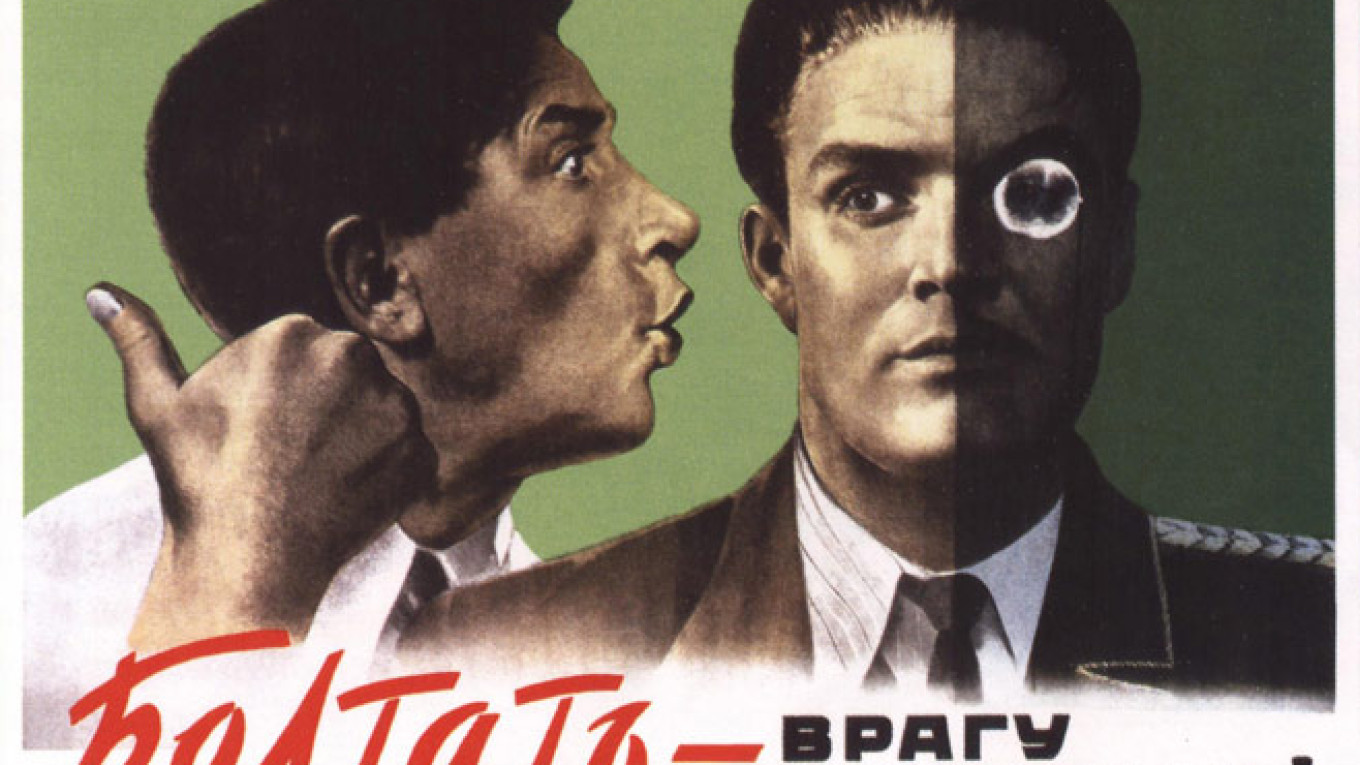

The phenomenon of informants appealing to state bodies such as the Investigative Committee has become rife in recent years, prompting some pundits to draw parallels with the purges of the 1930s, when people would denounce their neighbors, colleagues and love rivals to improve their living conditions, advance their career or curry favor with the authorities.

"Everything is sliding back to 1937: denunciations, secret informants and squealers," said Irina Khaly, a senior researcher at the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

"These people are not in the majority, but they seek career advancement and other benefits, so they are active," she told The Moscow Times in a phone interview.

A Sign From Above

Even when vigilant individuals request that law enforcement officers turn their attention to potential extremists, abuse of power or offenders of religious feelings, it is still the state that sends the relevant signal, said Alexander Cherkasov, a member of the governing board of the Memorial human rights advocacy group.

"Such groups of concerned citizens appear when there is a campaign that they can capitalize on," said Cherkasov.

During the past few years, there have been several such campaigns, according to analysts, including against loosely defined extremists, gay people and those perceived to be insulting the feelings of religious believers.

"The state is sending a signal as to who should be targeted, and then people begin hunting," Cherkasov said.

'A Concerned Citizen'

Sometimes denunciations are anonymous, and the Investigative Committee or prosecutors say in a statement that "a group of concerned citizens" has appealed to them to investigate an incident. On other occasions they are public, and often involve the State Duma or local deputies.

It was a group of unidentified individuals who investigators in St. Petersburg said had asked them to check a speech made at a January opposition rally by Maxim Reznik, a liberal deputy in the local legislative assembly, for extremism. Reznik was questioned last Monday and was later able to identify his denouncers. One of them was Timofei Kungurov, a municipal deputy in a St. Petersburg district, according to Reznik. Kungurov later confirmed to local media that he had been involved in the denunciation.

"You can find decent people in the government, and they told me who it was," Reznik told The Moscow Times.

The head of the legislative assembly, Vyacheslav Makarov from the ruling United Russia party, publicly defended Reznik and the incident blew over.

Imaginary Complainants

At the same time, it is possible that investigators sometimes use the "concerned citizens" formula to justify their actions when in fact the initiative came from investigators themselves, said Vladislav Inozemtsev, director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies think tank.

"I think this is either done by law enforcement agencies themselves, or inspired by them," Inozemtsev told The Moscow Times in a phone interview.

"The investigators want to create the illusion that they are fighting something real," he said, adding that he doesn't see parallels with the Stalinist purges of the 1930s.

Western countries have their own culture of informing, analysts agreed: At work, people might report a colleague for stealing a computer mouse, for example, and at home, people might think nothing of reporting their neighbors for illegally burning dead leaves in the yard.

The difference is that in Russia, people can report someone for allegedly offending their feelings, something that can neither be properly defined or investigated. While in the West snitching is a form of restoring order, in Russia it is used as a way to punish people, they said.

"In Western societies there is no room for these groundless denouncements, because they would not have any effect. Here we have the opposite situation, where making baseless denouncements is institutionalized. For instance, the whole foreign agents law is one vast misinformation campaign," said Gasan Guseinov, a prominent culturologist and philology professor at Moscow's Higher School of Economics.

"Individually, people can be driven by greed, envy or the desire for revenge, but we cannot exclude the possibility of people simply being mistaken and making a claim about someone that isn't true," Guseinov told The Moscow Times.

In 2012, Russia adopted a controversial law requiring all nongovernmental organizations engaged in loosely defined political activity and receiving any financing from abroad to register as "foreign agents," a term that carries connotations of Soviet-era espionage.

Contact the author at i.nechepurenko@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.