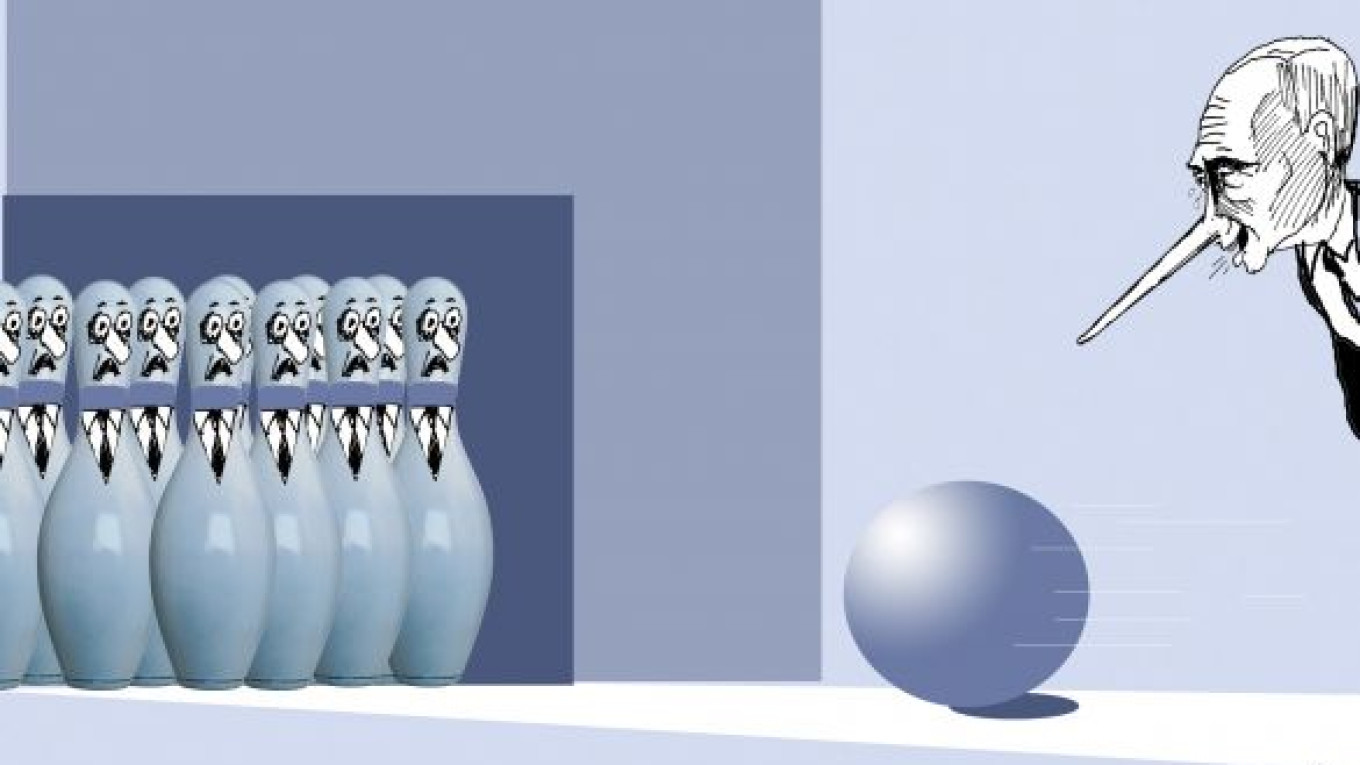

When Vladimir Putin created his power vertical and eliminated even the hint of civilian control over the government bureaucracy, he insisted that steps were taken to increase efficiency. But the main drawback to the power vertical soon became apparent: At critical moments, it begins to shake uncontrollably. In other words, all of the officials in the system begin quaking with fear. In that condition, they will do almost anything to save their own skins.

Putin is a good case in point. Worried over his own political survival, he rashly announced his "castling move" with President Dmitry Medvedev last September, even though he knew that it would create confusion in the ranks of subordinates. He saw no other option, however, and, as expected, the resulting uncertainties have sparked a flurry of infighting.

Something similar is happening now that the members of the ruling tandem are changing roles. While Putin and Medvedev discuss upcoming government appointments, senior officials at various ministries are going batty wondering who will determine their fate. Anxiety is highest among the siloviki. Due to the opaque nature of their security agencies and their absolute lack of accountability before the people, the struggle between siloviki clans is particularly fierce. For his part, Putin is only further straining nerves by preparing for each decision affecting the siloviki as if it were a secret operation.

Under such conditions, the only way the siloviki can get a feel of how things stand is to release a "leak" — and the more absurd the better — and then gauge the reactions of all concerned.

There have been at least two "leaks" recently.

Against the backdrop of the imminent and inevitable dismissal of Interior Minister Rashid Nurgaliyev, Nezavisimaya Gazeta unexpectedly announced that Interior Troops would no longer be part of the ministry and would instead directly answer to the president as his new National Guard. Furthermore, the newspaper reported that the National Guard would number 300,000 to 400,000 troops and include military cargo planes as well as resources from the Emergency Situations Ministry, airborne units and even the Navy. The plan essentially calls for creating a parallel army along the lines of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

If Putin really does harbor such plans, it can only mean that he considers the Russian people to be his main threat and that he is ready to use force to keep them down. Indeed, if the reported numbers are correct, the National Guard would have more troops than the army's ground forces.

Of course, the plan is completely infeasible, but not for ideological reasons. It is quite possible that Putin is prepared to refocus all of the siloviki structures on the fight against a domestic threat that he is convinced has been stirred up by foreign enemies.

Whatever the motivation, creating such a force is physically impossible. As has been repeatedly reported, the country is experiencing major demographic problems. From 2012 to 2025, only 600,000 to 650,000 young men will turn 18 every year. All together, almost 1.5 million troops would be needed to fill the ranks of both the army and the National Guard.

But the awkward newspaper report that led to the heated discussion forced Putin spokesman Dmitry Peskov to issue a denial in an attempt to reassure Interior Ministry and Emergency Situations Ministry officials that their jobs were secure.

Still, Defense Ministry top brass remain worried. The tone of statements made by Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov at the last ministry collegium left almost no room for doubt: He considers his mission accomplished. In his view, military reforms are nearly completed.

Serdyukov has no cause to worry about his own fate. He can be certain that Putin has reserved a choice position for him in his new administration. I suspect that he will be appointed secretary of the Security Council, an agency now charged with overseeing the Defense Ministry and siloviki structures as well as contributing to the formulation of foreign policy. The problem is that Serdyukov's Defense Ministry staff do not know who will replace him and what fate awaits them. And this gave rise to the second leak: Serdyukov and his closest associate, General Staff head Nikolai Makarov, have supposedly asked that they not be kept on in their current posts in the next government. Their replacements are reportedly Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin at the Defense Ministry and ground forces commander Alexander Postnikov at the General Staff.

Of course, all of these leaks are complete fiction. The point is not whether Serdyukov really wants to remain defense minister. Experienced members of Putin's inner circle like Serdyukov and Makarov would never openly break the unspoken rule — especially binding on members of the siloviki — that they silently and willingly accept whatever post Putin offers them. As a rule, any attempt to dictate terms to Putin will end badly for the person foolish enough to try.

This particular leak is a sort of "aggressive reconnaissance" designed to see who will refute the information and how. For example, would the authorities refute plans to appoint Postnikov as the new head of the General Staff? If so, the military brass could make their plans accordingly.

All of this confusion and anxiety comes at a price. Major government agencies are practically paralyzed, and what would happen if a real crisis were to occur now? Commanders are hardly prepared to carry out orders handed down from superiors whose own fates are in limbo and who are therefore not in a position to assume full responsibility for their orders.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.