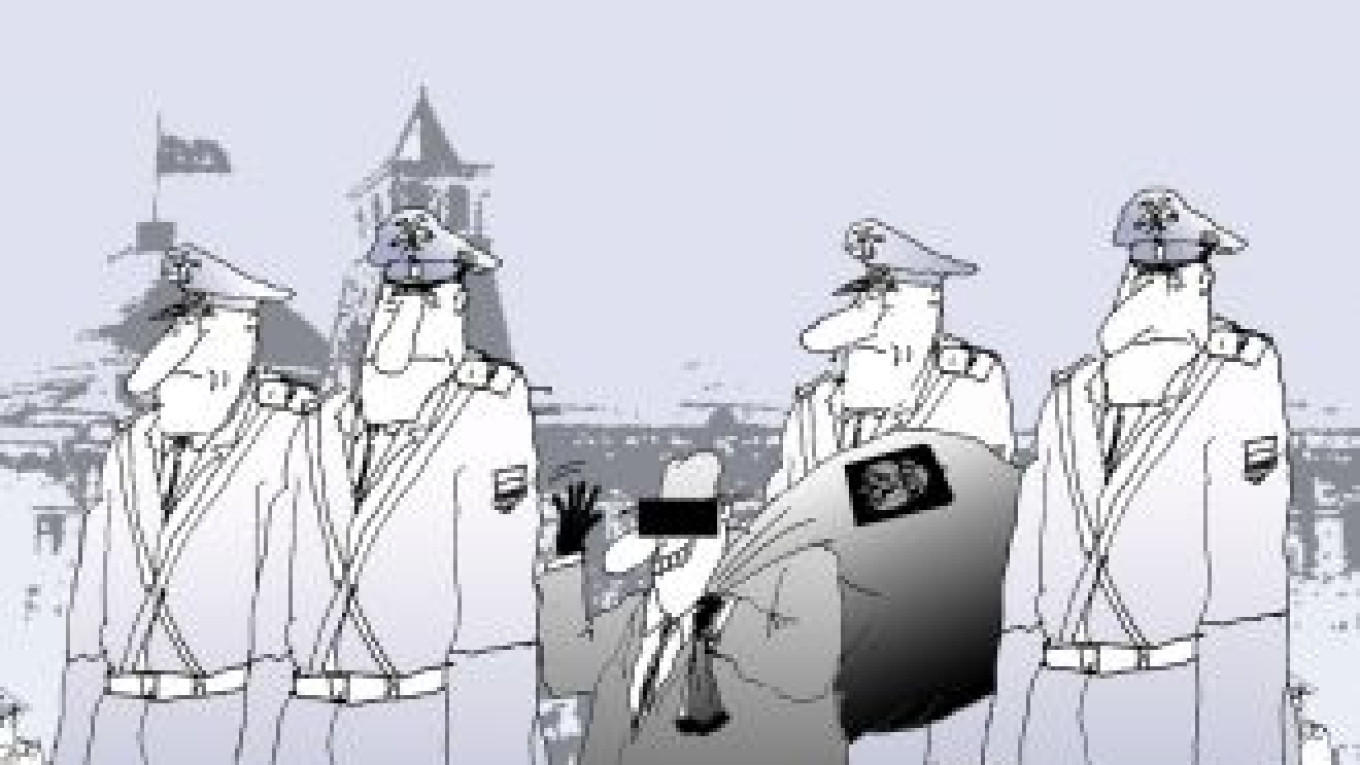

The gap between Russia’s authorities and citizens has become larger than ever. The country’s kleptocracy has degraded to such a level that criminal gangs and government officials have teamed up to create powerful organized crime syndicates. This was demonstrated in the recent Kushchyovskaya tragedy, but there are hundreds — if not thousands — of Kushchyovskayas across Russia.

The fact that President Dmitry Medvedev’s recent state-of-the-nation address to the Federal Assembly was almost completely devoid of any reference to the battle against corruption demonstrates that it is no longer a Kremlin priority. On International Anti-Corruption Day on Dec. 9, Kremlin chief of staff Sergei Naryshkin gave a vague, weak assurance to the press that the government was still fighting corruption and that it has achieved some success in the battle.

But the Kremlin has gone beyond uttering empty words about fighting corruption and trying to sweep the problem under the carpet. Now, it is actively defending corrupt officials and launching attacks against those who expose corrupt officials.

Prominent lawyer and blogger Alexei Navalny obtained materials from an official 2008 Audit Chamber review of the activities of the state-owned monopoly Transneft, which built the East Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline. According to the documents he posted on the Internet, exorbitant price gouging caused the state to lose roughly $4.5 billion on the project. In any open, democratic state governed by the rule of law, this finding would have resulted in public outrage, the creation of an independent investigative committee on a parliamentary level with an independent investigator, prison sentences for those found guilty of corruption and fraud in a court of law and the return of the stolen funds and property to state coffers.

But in Russia, everything works in the exact opposite way. The Audit Chamber classified its report to avoid public scrutiny, despite the fact that according to the Constitution, it is a state agency under parliamentary control whose very function — at least on paper — is to work openly and transparently to protect citizens against government abuse. One of the chamber’s auditors made a pathetic attempt at “damage control” by saying in effect, “Yes, money was stolen, but not as much the media reported.”

Typical to its role as the Kremlin’s own legislative branch, the State Duma and the Federation Council have remained silent on the Transneft scandal.

Moreover, instead of opening dozens of criminal cases into top Transneft (and Kremlin) officials, Russia’s law enforcement agencies have opened an investigation into Navalny, the person who is blowing the whistle. The authorities are attempting to bring trumped-up charges against Navalny when he worked a year ago as an adviser to Kirov Governor Nikita Belykh — allegations that even Belykh himself labeled as absurd. And numerous pro-Kremlin web sites are accusing Navalny of making false corruption charges against large state corporations as a form of commercial blackmail to benefit competitors.

Framing and persecuting the whistleblower is a tried-and-true tactic for the Kremlin, Interior Ministry and other government agencies to cover up their own crimes. This tactic was used against lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who exposed an Interior Ministry scheme to embezzle $230 million from companies owned by his client, Hermitage Capital. Similarly, when Novaya Gazeta co-owner Alexander Lebedev reported that a similar amount of money had been embezzled from Rossiisky Kapital bank, armed police officers in masks were sent to the bank in early November to seize company documents. Needless to say, Lebedev’s allegations that millions of dollars were stolen from Rossiisky Kapital have not been investigated.

In addition, no serious investigations have been made into attacks against the opponents of the construction of a new Moscow-St. Petersburg highway through the Khimki forest, including the brutal beating of Khimkinskaya Pravda editor-in-chief Mikhail Beketov or Kommersant reporter Oleg Kashin. What’s more, Yevgenia Chirikova, one of the leaders of the movement opposed to the highway, reported that a firm she and her husband own has come under the scrutiny of law enforcement agencies.

Investigations have also been blocked into numerous corruption scandals in Sochi connected with preparations for the 2014 Winter Olympic Games. Alexander Tkachyov — governor of the Krasnodar region, which includes Sochi — was seen in a photograph from Medvedev’s presidential inauguration alongside reputed Kushchyovskaya gang leader Sergei Tsapok, reportedly a former United Russia member. Yet Tkachyov continues to govern the region — no questions asked.

Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin try to convince Russians that they are fighting corruption by going after lower-ranking scapegoats, such as the young investigator from Kushchyovskaya, Yekaterina Rogoza, who posted a video on the Internet exposing wrongdoing by high-ranking regional police officers and prosecution officials. She has since become the subject of criminal charges by those same authorities. But high-ranking government and law enforcement officials — those who? are the most corrupt — have full protection from criminal investigations.

Medvedev should study how former Singaporean leader Lee Kuan Yew won the battle against corruption. Whenever Lee is asked how he managed to turn the heavily criminalized port city-state into a thriving international business center that is virtually free of corruption, he always responds by saying, “The battle against corruption must start at the top.”

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.