Dating back to pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg, the robe was sewn for the prince to sit for portraits, but its sable trim was all but worn off at Parisian soirees in the early 1960s by his protege, Victor Contreras, who now preserves the robe along with photographs and personal papers documenting Rasputin's murder.

One of Mexico's best-known sculptors, Contreras is sprightly despite his 65 years, and boasts that he was even more handsome and talented in his youth. "My favorite topic is myself, of course!" he said in a recent telephone interview.

Contreras ran away from home as a teenager. Lying about his age and bribing fake "parents," he enrolled in art schools in New York and Munich before finally settling down at the Ecoles des Beaux Arts in Paris. He was only 17.

In Paris, he met the Countess Ksenia Sheremetyeva, a descendant of the famous Russian aristocratic family. She invited him to lunch with her grandparents, the Prince and Princess Yusupov.

"I had no idea who they were at the time," Contreras said, laughing. "I was served like royalty, and there was this beautiful old gentleman sitting across from me."

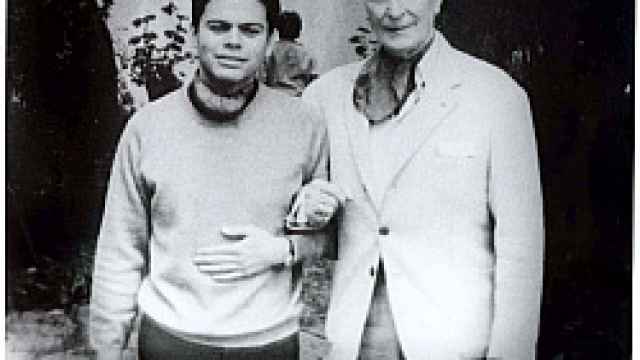

Courtesy Of Victor Contreras A photograph of Contreras and Prince Felix Yusupov in the 1960s. | |

"He was a very great soul," Contreras said, "a mystic, who could heal with the hands."

Indeed, the prince -- not unlike Rasputin -- had a reputation as a faith healer. He also claimed to have glimpses into the future. Contreras used to accompany the prince on visits to sick members of the Russian emigre community. Yusupov would place his hand on the patient's forehead and pray, and "the person would come back to life, back from death," Contreras said.

The young artist was invited to live at the Yusupovs' home in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, and he spent the next five years there. He described his relationship with the prince as that of an adopted son and his father. The family used to introduce him to friends as "the son who fell to us from heaven."

One forbidden topic was the prince's role in Rasputin's murder, which remained a source of shame for the family.

Courtesy Of Victor Contreras Contreras sculpting a bust of the prince. | |

On Dec. 29, 1916, Rasputin accepted Yusupov's invitation to dine at his Moika Palace, where the conspirators served him wine laced with cyanide. When the poison left him mysteriously unaffected, the conspirators shot him four times, clubbed him and tied him up before dumping the body in the Neva River. Three days later, the body was found in the frozen river, arms freed in an upright position, as if he had tried to claw his way out from under the ice.

The murder was never discussed at the Yusupovs' home in Paris, Contreras said, until one afternoon when the old prince "confessed everything."

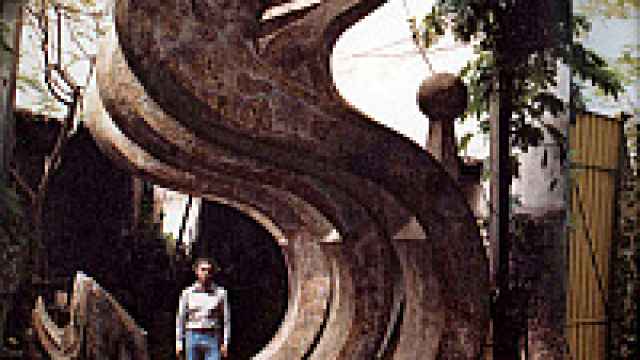

Courtesy Of Victor Contreras Contreras posing under one of his monumental sculptures. | |

Yusupov told him about his first meeting with Rasputin, at the Peterhof Palace outside St. Petersburg. The two established a mystic link, the prince recalled.

"The prince told me Rasputin looked him in the eyes, and he fell down under his gaze," Contreras said. "He felt the soles of the feet tingling, saw through the eyes of Rasputin. When the prince managed to stand, Rasputin stumbled in turn and cried out, 'Felix, together we could own the world!'"

The artist described Yusupov as the antidote to Rasputin. "The same powers that man had, he had in good," Contreras said. "He vanquished him!"

But the artist was unwilling to say anything about Rasputin's murder in the interview. He said he was preserving the prince's private papers, entrusted to him by the family, to publish along with the revelation of Yusupov's testimony.

Contreras plans to turn his home into a museum, featuring artifacts that he inherited from the Yusupovs.

One of those artifacts is a striking cobalt-blue and red glass chandelier. Contreras said it originally hung in the lower chambers of the Yusupov palace, where a reproduction now sets the Rasputin murder scene for St. Petersburg tourists.

Contreras also has 14 portraits of the Yusupovs, including one by Ilya Repin. He is most attached to a portrait of Felix Yusupov and his oldest brother, Nikolai Yusupov, by Nikolai Bogdanov-Belsky. When Princess Yusupov first offered it to him, remarking on his likeness to Nikolai, the artist refused, fearing that he might share the fate of first-born Yusupovs. In an eerie pattern that went back centuries, all but one of them died before the age of 26.

But the portrait now hangs over his fireplace, brought undeclared through customs to Mexico, along with all the other historic objects.

Contreras is still close to Yusupov's granddaughter. He accompanied her to the 1998 reburial of Tsar Nicholas II and his family at the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg, where he was dubbed a Knight of Malta by Patriarch Alexy II. He was honored for his sculptures as the only remaining Symbolist artist in the world.

"The altar was in gold, it was divine, and that is how I ended my Russian experience," he said.

Contreras is best known for his monumental bronze sculptures. He boasts 74 public works installed in 34 countries. One of them, the "Immolation of Quetzalcoatl" in Guadalajara, Mexico, was one of the tallest sculpture sets in the world when he created it in 1982. It consists of four allegorical sculptures set around a central, 25-meter-high bronze figure representing the plumed serpent god of the Aztecs.

Contreras is now working on a project to be presented at the 2008 Venice Biennale. He has also worked tirelessly for the opening of a Guggenheim Museum in Guadalajara, with the groundbreaking due for next fall.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.