NEW YORK — Nukus, the capital of a poor Uzbek region, has a secret: a museum hidden away that is packed with Russian avant-garde masterpieces.

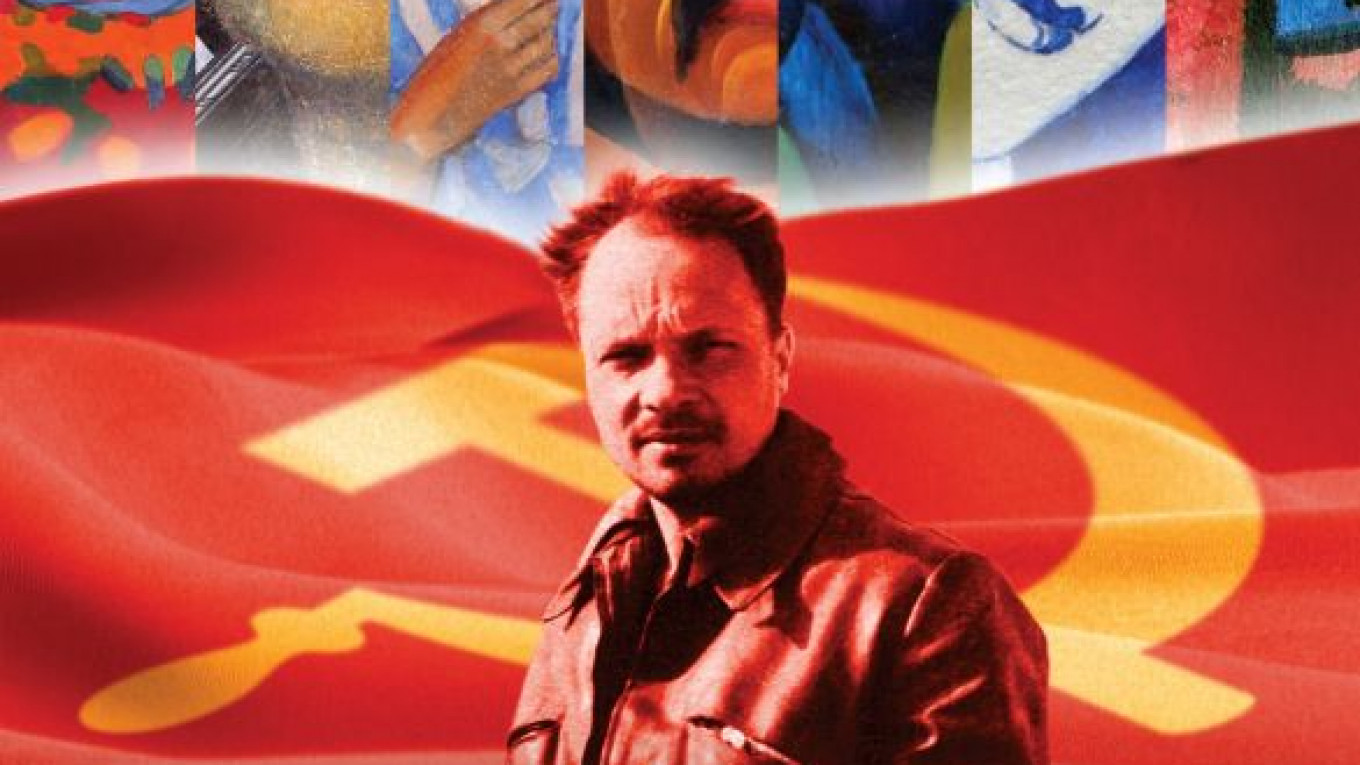

A new documentary, “The Desert of Forbidden Art,” looks at this remarkable museum and at Igor Savitsky, the tireless art collector who saved tens of thousands of paintings by banned Soviet artists and in turn created the world’s second-largest collection of Russian avant-garde art.

Avant-garde artists, whose paintings form the Savitsky collection, fled Russia for Uzbekistan in the 1920s and 1930s, in search of a place where they could continue painting in the way they wanted as the Russian art world moved dictatorially toward socialist realism.

Karakalpakstan, the Uzbek region where Nukus is located, was until the late 1930s relatively sheltered from the Soviet government’s cultural control providing artists such as Alexei Rybnikov, Alexander Volkov and Mikhail Kurzin with the freedom to continue their work.

Influenced by the European avant-garde when living in Russia, they were inspired by the colorful and diverse Uzbek folk art and began incorporating it into their style.

“One of the most fascinating things about the collection in Nukus is that it really shows how the local artists adapted these local styles to their own domestic needs,” said John Bowlt, professor of Slavic literature and languages at the University of Southern California. “It shows that all kinds of things might have happened in a positive way, had not social realism in 1924 been imposed on Soviet culture. That’s the main merit of the collection, it shows us what happened and shows the potential of the last heroes of the avant-garde.”

Arriving in Uzbekistan in the 1950s as part of an ethnographic expedition, years after many of the local Russian artists had been killed or sent away to the gulag during Stalin’s Great Purge, Savitsky began searching for and gathering the lost treasures of “anti-Soviet” Russian avant-garde in Uzbekistan and Russia. His efforts culminated in the creation of the Nukus museum, which held 50,000 works of once-forbidden art. Until his death in 1984, Savitsky dedicated all his time to the upkeep of the museum, carefully manipulating local officials to get funding for the project.

“When Savitsky rescued these paintings, [he] stashed them in this folk art museum even though nobody wanted them,” said Amanda Pope, co-director of the documentary along with fellow filmmaker Tchavdar Georgiev.

Savitsky’s successor as protector of the art is Marinika Babanazarova, the present-day director of the museum, who is the central voice of the new documentary. She is currently holding off the Uzbek government, who recently moved to demolish one of the museum buildings forcing an emergency evacuation of hundreds of works in just 48 hours, and private collectors, including Russian oligarchs, who want to buy the museum’s paintings.

Babanazarova refused to sell despite the museum’s desperate need for financial support and a lack of state funding, saying Savitsky’s legacy needs to be kept alive.

“The wonderful thing about the collection is that it is an organic entity, and it’s still the legacy of Savitsky, it’s in one piece, one place, and really there is nothing else to match that in the world,” Bowlt said. “It is such a monument, not only to one person, but to what was happening in the Soviet culture in the 1920s-1930s, that it really should be preserved precisely as a monument.”

Babanazarova has been loyal to the collection for 27 years, despite making $50 a month and facing pressure from the Uzbek government, which prevented her from traveling to the United States for the documentary’s screening at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Pope and Georgiev believe that the government’s attitude stems from Uzbekistan’s struggle to re-establish a cultural identity after the breakup of the Soviet Union, which for years “Sovietized” the Uzbek culture. “It is the new Uzbek national narrative into which the Russians still don’t fit in, and the painters in the Nukus collection are Russian,” Georgiev said. “Even though they adopted Uzbekistan as their second motherland, that part of heritage didn’t quite fit into the new narrative.”

“There is a danger that the Uzbek government will sell the Nukus collection for personal needs,” Pope said.

But as long as Babanazarova heads the museum, Pope and Georgiev believe, the government won’t touch the collection. One of the reasons they made the documentary, they say, is to try to shift Uzbek authorities’ attitude to seeing the collection as a tourist attraction and a cultural treasure.

Pope and Georgiev are currently in talks with the art center Garage about organizing a screening there.

See for more about the documentary.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.