Despite President Dmitry Medvedev’s appeal to political parties to avoid whipping up dangerous nationalistic and xenophobic sentiments in their campaign slogans or political platforms, it is already clear that some parties have begun doing exactly that. I suspect that the clan allied with Prime Minister Vladimir Putin is most responsible for placing the issue of “protecting Russians against ethnic minorities” on the front burner among Kremlin-sanctioned parties in this election season.

Take, for example, the Liberal Democratic Party. During its convention on Sept. 13, it unveiled the slogan ?€?For Russians!?€? that will serve as its major platform going into the December State Duma elections. The Liberal Democratic Party list includes the son of Yury Budanov, who was convicted of killing a Chechen girl. The list also includes the lawyer who defended Russian ultra-nationalists convicted of murdering attorney Stanislav Markelov and journalist Anastasia Baburova.

In addition, Dmitry Rogozin, the country?€™s leading nationalist, has announced his plans to return to Russia and play an active role in domestic politics. Tellingly, the Kremlin invited Rogozin to give a keynote speech at the Yaroslavl Global Policy Forum earlier this month in which he spoke about protecting Russians against discrimination from the country?€™s minorities.

It would have been impossible for Rogozin to speak so openly and freely about the ?€?Russian question?€? on state-controlled television and at a Kremlin-sponsored international forum without Putin?€™s approval.

By placing the Russian question at the center of the national agenda, the Kremlin gains a number of short-term benefits.

First and most important, the focus on the Russian question deflects attention away from the country?€™s largest problems — such as corruption, social stratification and lawlessness ?€” which have become far worse under Putin?€™s rule. Exploiting the Russian question enables the authorities to manipulate public opinion and to instill in people?€™s minds the belief that they live poorly because of ethnic minorities who, the argument goes, trample over Russians?€™ rights by invading Russian cities, seizing and monopolizing key sectors of the economy through their organized crime groups and refusing to respect Russian cultural norms or the law.

According to a Levada Center poll in January, 15 percent of the population fully supports the slogan ?€?Russia is for Russians,?€? and another 45 percent believe that it would be good to evict non-Russians using ?€?reasonable methods.?€? With the nationalistic segment of the population growing each year, it creates a great temptation for the authorities to exploit these sentiments.

Third, another Kremlin motive behind the Russian question might be to spark a new interest in voting in both federal and local elections. Russians have largely ignored elections because of traditional voter apathy and cynicism, which have only been exacerbated by the instances of massive election fraud over past few years. Playing the nationalist card may be the only way to increase voter turnout, which, the authorities believe, would help legitimize the future composition of the State Duma and the president.

History shows that authoritarian leaders, when faced with eroding public support and declining economic conditions, often cling to nationalism and xenophobia as the last lifeline to preserve their hold on power. State-sponsored nationalism, however, can quickly spin out of control. Take, for example, former Yugoslav leader Slobodan Milosevic who in the last years of his rule replaced his socialist ideology with radical Serbian nationalism. This pro-Serbian nationalism quickly turned into chauvinism, followed by anti-Muslim ethnic extremism. History has shown that the slope from one to the other is, indeed, slippery. This is something Putin and his advisers need to bear in mind before they decide to push the nationalist button too hard.

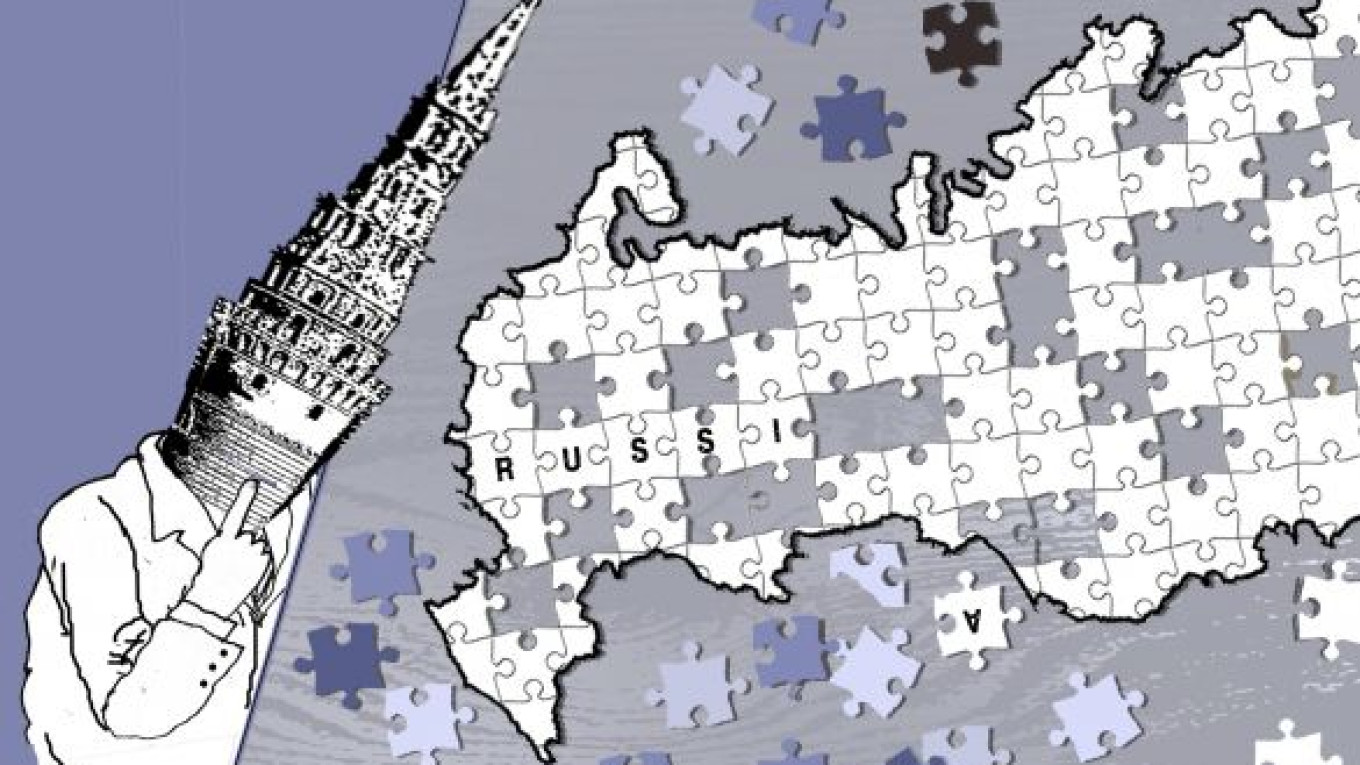

An aggressive government-sponsored policy aimed at demonizing minorities leads to a vicious cycle of violence and separatist movements that could easily destroy the state. The biggest danger for Russia is in the North Caucasus republics, but there is also potential for separatism and ethnic violence in Tatarstan, Bashkortostan and other regions dominated by minorities. The Serbian nationalism championed by Milosevic contributed to the final bloody collapse of first Yugoslavia, and then Serbia itself. The same thing could happen in Russia.

Rogozin is completely wrong when he says one of the biggest problems facing Russia is the ?€?main line of tension between Russians and immigrants from the North Caucasus.?€? The real reasons for Russia?€™s problems are weak state institutions, rampant corruption, lawlessness, injustice and the lack of normal conditions for economic and social development. The rise in interethnic tensions is a symptom of these weaknesses, not the cause of them.

The Kremlin should categorically reject the slogan ?€?Russia for Russians?€? and replace it with ?€?Russia for all citizens of Russia.?€? Only this approach will produce the breakthrough needed to achieve a better future for Russia.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio and is co-founder of the opposition Party of People?€™s Freedom.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.