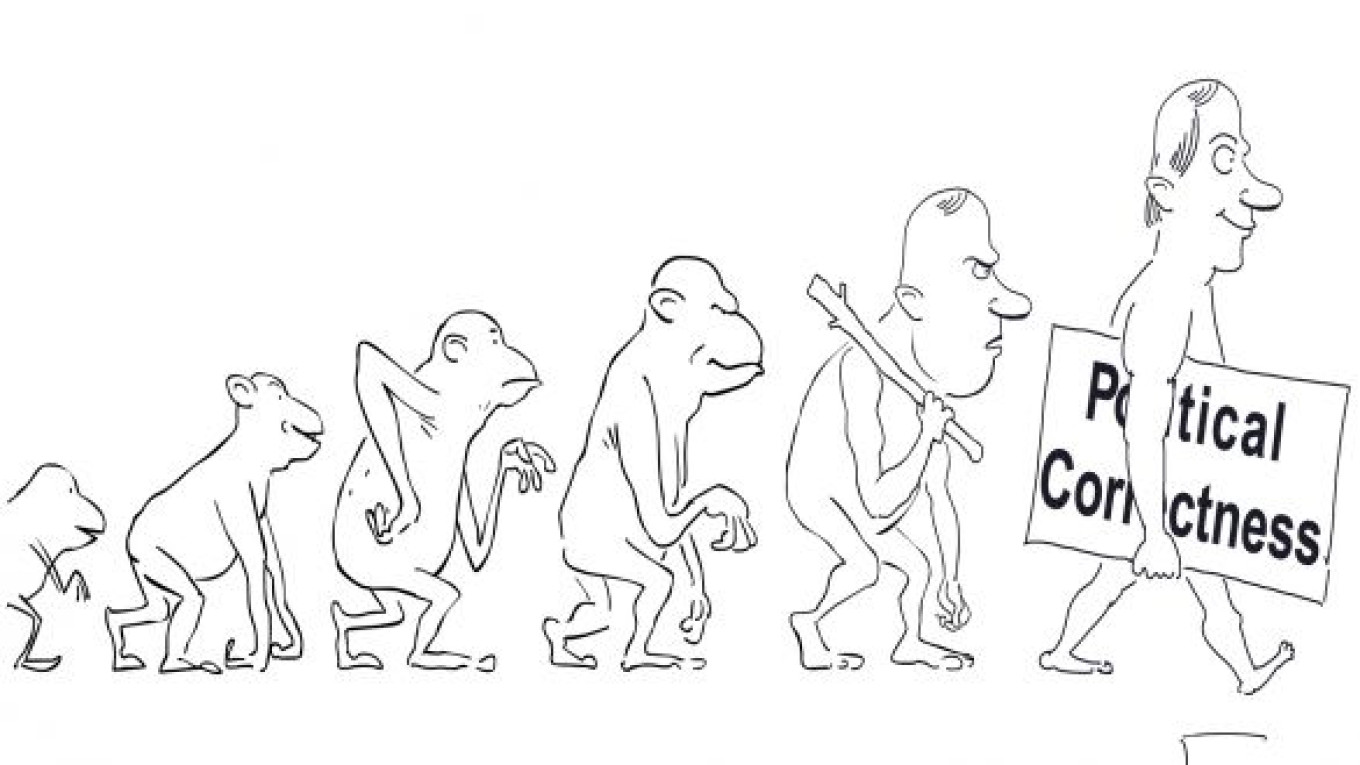

The term "political correctness" evokes an immediate negative reaction among many Russians. They usually criticize its extreme form in the United States, where, some believe, a man can't even compliment a woman on her appearance without being accused of sexual harassment.

This, of course, is an exaggeration, but it is true that political correctness is often taken to extremes. Recall former Harvard University president Larry Summers, who resigned under pressure from colleagues and public opinion when he commented in 2005 that women tend to lag behind men in the technical and engineering fields. Although his comments were based on data from authoritative academic research, which he cited during his speech, his words were considered "politically incorrect" and grounds for dismissal.

Russians like to say that political correctness is "not for the Russian climate," that they are too accustomed to calling things the way they see them. But in measured doses, political correctness could be very useful for Russia, especially as a way to foster greater ethnic tolerance in society. It could also pay financial dividends.

In my 15 years working in Russia, I once received an email from a co-worker who sent the following message to hundreds of colleagues: "Apartment for rent. Slavs only."

I was shocked. The Russian who sent the message knew that his co-?workers were from various ethnic groups and would read the email. Did he really not understand that this message would offend his non-?Russian colleagues?

I tried to understand the reason behind this ugly incident. Was it a case of his upbringing? A banal case of racial prejudice? Or complete indifference to those whom ethnic Russians call "chuzhiye" — people of other ethnicities? It was a probably a combination of all these factors.

When I confronted the sender, I asked him how he would have felt if he worked in a New York firm and received an email with this announcement: "Apartment for rent. Russians need not apply." He didn't reply.

Unfortunately, this type of racism is all too common in Russia. But there are far worse examples. In late 1998, several months after the August default and ruble crash, State Duma Deputy Albert Makashov publicly used a word that is highly offensive to Jews. He also called for a quota for Jews in government posts and made an implicit appeal to Cossacks to destroy Jewish homes. Also during this period, Deputy Viktor Ilyukhin, a strong Makashov ally, blamed the Jews for Russia's "genocide" in the 1990s.

In any other country with a modicum of political correctness, fellow lawmakers and public opinion would have forced these politicians to resign. Some countries would have charged them under hate-speech or extremism laws. Neither happened here. In fact, the Duma couldn't even garner enough votes to pass a resolution condemning Makashov or Ilyukhin. Instead, pro-Makashov deputies blamed the media — presumably run by Jews — for "exaggerating and inflaming" the situation.

Nonetheless, many in Russia believe that American political correctness is immersed in hypocrisy and double standards. "Americans think one thing," I am often told, "say the complete opposite and cover it up with a fake smile. It may not always be pretty what we say about other nationalities, but at least we speak our minds — and the truth."

As it turns out, in the politically correct United States, there is no real freedom of speech, Russians tell me, while in politically incorrect Russia, you can say whatever you want.

The only problem with this is when the freedom to speak your mind takes the form of hate language aimed at non-ethnic Russians, it fractures and destroys the country.

The benefit of political correctness is that it can establish widely accepted language norms and etiquette. When society limits hate speech, it also helps form a general culture of tolerance for minorities.

Political correctness can also have widespread benefits for society's economic and social development. It can create a general atmosphere that allows for the career development of talented and innovative people of all nationalities.

This, of course, applies to Russia as well. The country would only benefit by promoting its most talented people of all nationalities and by suppressing the temptation to prejudge people according to fixed racial and ethnic stereotypes. In this way, society opens up new opportunities for all of its talented members — for ethnic and nonethnic Russians alike.

It is axiomatic that open and tolerant societies are far more successful and prosperous than closed and intolerant ones. The amazing success of Sergei Brin at Google is a vivid example. Brin grew up in the Soviet Union and emigrated to the United States in 1979 when he was 6. His parents emigrated precisely because state-sponsored and grassroots anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union had limited their educational and career possibilities. They didn't want the same for their son.

Today, the net worth of Brin, 38, is $18.7 billion, making him the 24th-wealthiest person in the world, according to Forbes magazine.

True, the level of anti-Semitism has decreased markedly since the Soviet period and the ugly incidents of the late 1990s. But the level of intolerance toward other minorities — mainly people from the Caucasus and Central Asia — remains high.

I have heard from many Russians who oppose U.S. political correctness that this phenomenon would destroy Russia if it is ever inculcated here. But the opposite is true. If applied in reasonable doses, political correctness can help Russia develop and modernize — not only culturally, but economically and socially as well.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.