As Russia's relations with the West plunge to new lows over the simmering conflict in eastern Ukraine, Russia continues its pivot East toward a new strategic partnership with North Korea.

Recent efforts at closer bilateral cooperation in the political, economic and military spheres reveal a Russian bid to project more power in its Pacific near abroad and further defy the West across the globe.

On March 17, the Kremlin officially confirmed that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un will travel to Moscow in May, his first visit abroad since inheriting control after the death of his father, Kim Jong Il, in 2011.

Kim is one of 68 heads of state invited by Russian President Vladimir Putin to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the Soviet Union defeating Nazi Germany in World War II, though only 26 leaders have confirmed their attendance.

With rumors swirling since December, speculation still abounds as to whether the ruler of the reclusive nation will make such a publicized trip. Regardless, Putin can keep soaking up global attention to divert away from Western attempts to isolate him. His recent 10-day absence created a media frenzy that buried news on violations of the shaky cease-fire in eastern Ukraine.

"He likes these high-profile events," explained Richard Weitz, director of the Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute. "It'll make him feel good. It'll make him think that he's still an important international leader."

Some analysts agree that Putin's invitation to Kim is largely an empty symbolic gesture. The May celebration represents an opportunity to flaunt his international prestige and showcase Russia's global role.

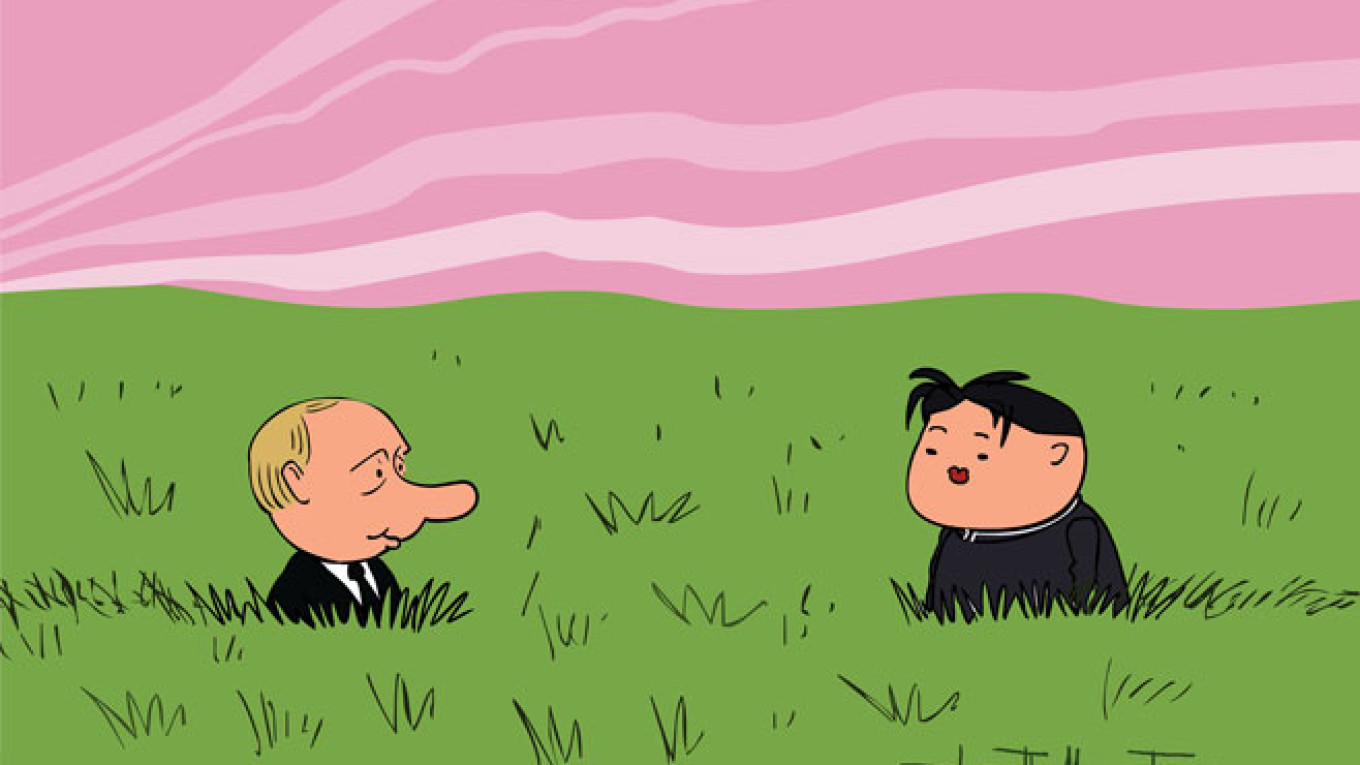

Furthermore, the appearance of Putin and Kim together, heads of two states targeted by economic sanctions, creates a provocative image of anti-Western solidarity. In blunter terms, it is another jab to the battered body of the West.

Others believe that there is a foreign policy of more substance in the works. "North Korea is a convenient friend for Moscow — it is anti-American and it is a key part of Asia," said Dr. Leonid Petrov, an Asian Studies professor at the Australian National University. "Russia lost many of its traditional allies — it needs friends, both economically and politically."

However, recent efforts at improved bilateral cooperation reveal that Kim's visit to Moscow likely signifies more than just Putinesque political theater. Russia is making a concerted attempt to strengthen its influence in the Pacific.

It is not particularly surprising that Kim will have his first trip abroad as North Korean leader to Russia, instead of China. In the last few years, Pyongyang's close relationship with Beijing has deteriorated mainly due to stronger Chinese opposition to the North Korean nuclear weapons program.

North Korea and Russia share a long diplomatic history that rivals North Korea's relationship with China. Kim Il Sung, the revered founder of the North Korea state, served in the Soviet army, receiving special military and political training in communist guerrilla tactics in the 1940s.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union became the primary benefactor of its eastern neighbor until 1991. Though China then filled the role of aid provider, the late Kim Jong Il still occasionally traveled to Moscow during his rule, with the last visit a few months before his death in 2011.

The widening gap in Chinese-North Korean relations offered a chance for Russia to advance its strategic presence in Asia even while embroiled in eastern Ukraine. It appears that Putin has seized the tactical initiative once again.

In 2012, Russia first agreed to forgive 90 percent — $10 billion — of North Korea's Soviet-era debt and reinvest a significant portion into energy, health care and educational projects between the two countries. The deal was borne out last year with political promises transforming into closer economic cooperation.

In October, Russia announced a joint venture to reconstruct North Korea's railroad system over the next 20 years in exchange for access to mineral resources. Other collaborations under review include shared advanced development zones to boost bilateral trade and a lucrative pipeline through North Korea to deliver Russian gas to South Korea, the world's second-biggest gas importer and closest Western ally in the region.

Russia is clearly aiming to increase its influence in Asia, especially to exploit energy markets beyond Europe to keep the Russian economy afloat amid Western sanctions over Ukraine and the global drop in gas and oil prices.

Russia's political and economic charm offensive seems to be gaining ground. North Korea recently declared 2015 to be a special "year of friendship" with Russia.

More notably, Valery Gerasimov, the chief of staff of the Russian armed forces, released plans last month for joint military drills with North Korean forces, an ostensible counterpunch to annual U.S.-South Korea training exercises.

Kim's anticipated visit to Moscow is ultimately the diplomatic culmination of these recent improvements in the political, economic and military spheres of Russo-North Korean relations.

In May, Putin will certainly capitalize on the pomp and circumstance of 26 heads of state celebrating Victory Day at the Kremlin, parading his relevance as a world leader. But amid the political theater there will be machinations of substance with implications for the international security environment.

The interactions between Kim, Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping will speak volumes on Russia's ongoing efforts to project more power in its Pacific near abroad to the chagrin of the West.

Peter J. Marzalik is a freelance writer pursuing an M.A. in Security Policy Studies at George Washington University.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.