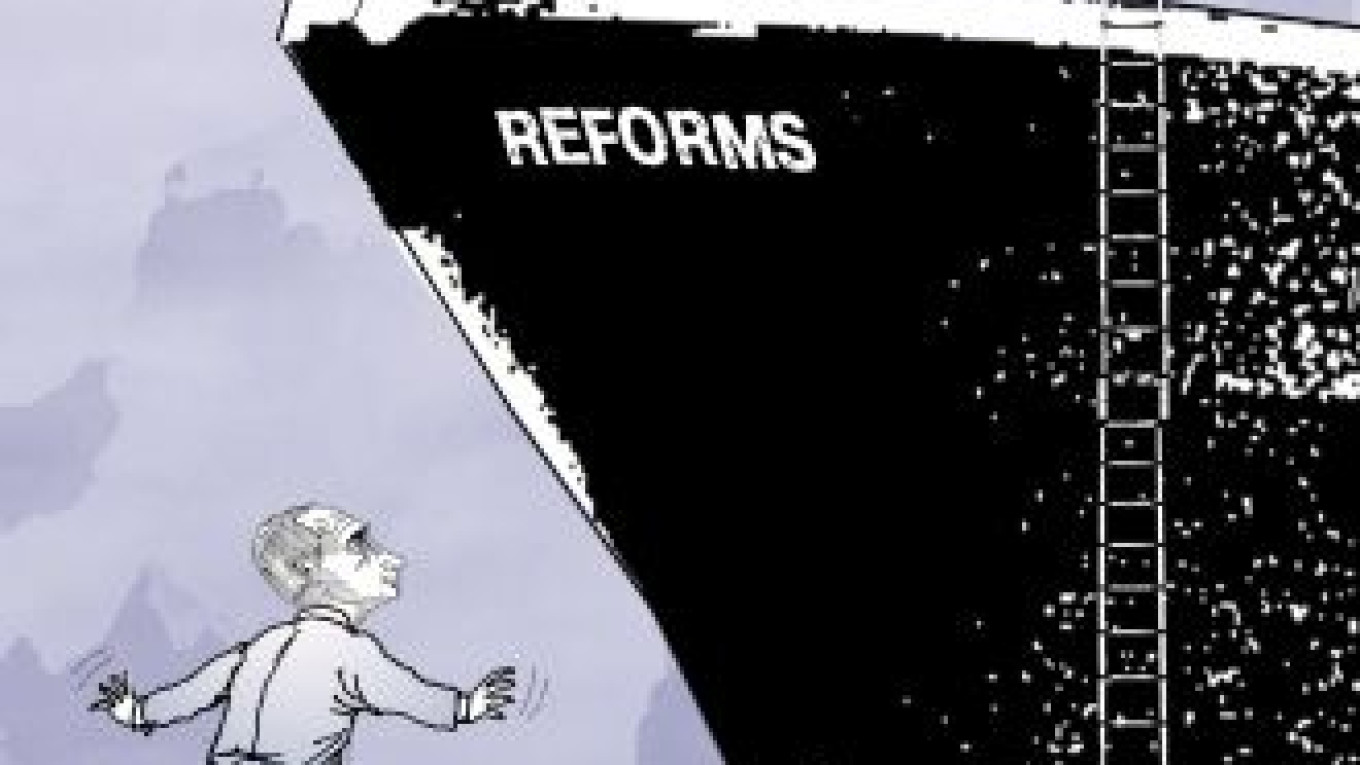

Russia's economic growth rate is causing serious concern. The fundamental problem is that Russia has almost reached full capacity. Growth is likely to stay low until Russia undertakes profound systemic reforms, but no such reforms are on the agenda.

Russia's gross domestic product grew reasonably well at 4.3 percent in 2010 and 2011. The growth rate dropped to 3.4 percent in 2012 and to an annualized growth of only 1.6 percent in the first quarter of this year. The Economic Development Ministry has cut its growth forecast for 2013 from 3.6 percent to 2.4 percent, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, or EBRD, to 1.8 percent.

There can be little doubt that the slowdown is real. The EBRD points out that the slowdown started in the last quarter of 2011, and it appears to have been driven by domestic demand, first less consumption and later investment.

President Vladimir Putin has persistently blamed external factors, notably the eurozone crisis. Yet international oil prices stayed high until April, whereas Russia's oil production increases minimally. Russia's gas production has long been stagnant, and the shale gas revolution in the U.S. has driven down global gas prices through the proliferation of liquefied natural gas supplies from all corners of the world. Global steel prices have fallen sharply because of declining import demand from China.

So far, the dominant explanation of Russia's declining economic growth is internal and not external, namely slowing domestic demand and supply. With an official unemployment rate of 5.7 percent, the country is working at full capacity and hardly has any real unemployment. Its problem is not demand but supply constrained by multiple bottlenecks.

After many years of quickly rising productivity, economic efficiency no longer increases much. The key problem is that competition on the domestic market has declined. The abating competition is best shown by the number of officially registered enterprises. From 1999 to 2005, it increased by a healthy average of 7 percent a year. It slipped from 2 percent to 4 percent annual growth from 2006-09. But in 2010, that number started declining, and this decrease is accelerating. From December 2012 to April 2013, the number of individual entrepreneurs slumped by 367,000 because of an increasingly hostile business environment. Inefficient state corporations buy more efficient oligarchic companies, which buy successful medium-sized enterprises. This is no way to run an economy. Until recently, the damage caused by an irresponsible economic policy was concealed by rising oil prices, but now it is becoming apparent.

There are few things Russia understands better than the importance of economic growth.? Putin sounded the alarm with his liberal economic advisers in Sochi on April 22 and in a meeting with his government on May 7. Yet he offered no direction, only complained in a Brezhnev-like fashion that ministers did not adopt a sufficient number of decisions.

Russia's always-intense economic policy discussion has heated up. Since 2000, liberals from the large Yegor Gaidar-Anatoly Chubais team have dominated the policy debate. They have advocated conservative fiscal and monetary policy, deregulation, privatization and international integration. Their views inspired all the major official reform programs: the German Gref program of 2000, the Russia 2020 program of 2008 and the Strategy 2020 program of 2012. Much of the Gref program was implemented, but the latter two programs had little impact on real life.

While officially condoning such liberal policies, Putin has actually pursued the opposite course. Since the government confiscation of most of Yukos' assets in 2004, Putin's real policy may be described as a mixture of state and crony capitalism. State intervention has proliferated as has re-?nationalization through more or less voluntary state purchases of companies. Of the liberals' policies, Putin has only embraced fiscal conservatism.

As economic growth has abated, an old star has re-emerged, Sergei Glazyev. The well-known statist and nationalist foreign trade minister from 1992 to 1993 became economic adviser to the president last July. He is advocating the policies Putin is actually pursuing: state capitalism, re-nationalization, concentration of enterprises and militarization of the economy as a means of modernization. Their common favorite theme is the protectionist Eurasian Union, which causes costly trade diversion to its members because of its high customs tariffs and small size.

Most daringly, Glazyev calls for a much looser fiscal and monetary policy, which he incredibly claims will raise economic growth to 8 percent. His well-publicized program sounds very Soviet, but cleverly he refers to President Ronald Reagan's strategic defense initiative as his model.

The worried liberals have gone on a broad counteroffensive with former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin explaining the need for fiscal and monetary conservatism. Prominent economist Vladimir Mau is most eloquently making the case for liberal structural reform. Interestingly, Mau, who is a consummate political insider, has called for full democracy as a precondition of successful economic reforms.

So far, the president seems unimpressed with the liberal reform agenda. He defends the mismanaged Gazprom tooth and nail. He pins his hopes on Rosneft, which has emerged as the likely next uneconomical national champion. Putin has repeatedly expressed wildly exaggerated expectations for economic benefits from the flawed Eurasian Union, and he supports massive military expenditures for no obvious purpose.

Putin's only remaining liberal policy is fiscal and monetary conservatism. The big question is whether he will follow Glazyev's siren song and adopt stimulus. Given that Russia already has full employment and annualized inflation of 7.2 percent, any stimulus —? fiscal or monetary — is likely to result in nothing but inflation. Yet given his current mood, it would be all too logical for Putin to try it. ?

In fact, that might not serve the nation all too badly. Sooner or later, the fundamental truth will dawn upon Russians. The spectacular economic growth of 7 percent a year that the Russian nation enjoyed from 1999 until 2008 was not caused by Putin, who became president one year after its start, but by the arduous but sensible market reforms that President Boris Yeltsin pursued in the 1990s. During Putin's rule, the Russian economy surfed on the global commodity boom, whose end is near.

As late Yegor Gaidar emphasized in his book "Collapse of Empire," the end of cheap oil is the beginning of reform for Russia.

Anders Aslund is a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.